India’s Unfinished Quest for Great Power Status

The Unfinished Quest: India’s Search for Major Power Status from Nehru to Modi

By T.V. Paul

Oxford University Press/May 2024

Reviewed by Peter Jones

August 4, 2024

What makes a country a major power? Is it purely a question of hard power, or are more intangible factors involved? Is this status something a nation can claim unilaterally, or is the recognition and acceptance of other such powers the key to one’s arrival in the club?

These are questions Prof. T.V. Paul of McGill University explores with respect to India’s decades-long quest for major power status. Paul, a leading thinker and writer on both the broader power shifts that define the international order and on India specifically, is well placed to do so.

India’s evolution as a global power over the last half-century can be tracked as a parade of key political leaders, per this book’s subtitle — from Jawaharlal Nehru to Indira Gandhi to Manmohan Singh to Narendra Modi — as well as via a perpetual churn of competing tensions: between its colonial legacy and its nationalist sinews; between its timeless faith traditions and its status as a tech giant; between its legacy as the world’s biggest democracy and the domestic and international pressures of creeping authoritarianism. This book explores the ways in which those and other themes have defined India’s place in the global order.

In The Unfinished Quest, Paul begins by defining “major power” status as encapsulating four hard power issues: military capability, economic prowess, technological/knowledge capability and demography; and six soft power issues – normative position, leadership in international institutions, culture, state capacity, strategy/diplomacy and effective national leadership. The rest of the book analyzes India’s quest to capture this status. “Currently, India is aiming at becoming a ‘leading power,’ not just an ‘influential power'”, writes Paul. “In other words, the equivalent of a twenty-first century great power.”

Certainly, major power status is not unrealistic. India is the world’s most populous country and the fifth-largest economy (projected by some to be the second largest by mid-century). It is the heir to one (or, indeed, several) of the world’s great civilizations. It is a major player in engineering, pharmaceuticals and IT, and one of only five countries to have landed a craft on the moon. That English remains India’s second national language, the language of business and government, and the language in which university courses are taught is both an asset to the country’s status as a global player and a key factor in the virtual borderlessness between Silicon Valley and Bangalore.

‘Currently, India is aiming at becoming a ‘leading power,’ not just an ‘influential power’, writes Paul. ‘In other words, the equivalent of a twenty-first century great power.’

These impressive lists go on, yet are not entirely what they seem. Persistent, grinding poverty and chronically poor governance dull much of the lustre. India supplanted Britain as the world’s fifth largest economy in 2022, but per capita GDP in Britain is $47,000, as compared with $2,500 in India. Life expectancy, infant mortality and many other indicators are similarly skewed. That India is home to a large number of the world’s wealthiest people and hundreds of millions of its poorest speaks to a level of income inequality which has few peers in the world.

Regarding the traditional markers of major power status, India comes up short, largely, as Paul points out, because those markers were established long ago. The Permanent Five of the Security Council were codified in 1945 before Indian independence. The 1968 nuclear non-proliferation treaty (NPT) established the recognized nuclear weapons powers, which – surprise – aligned exactly with the P5.

It would not be until 2005 that India would achieve an exemption to its status under the NPT (which PM Manmohan Singh would refer to as “escaping nuclear apartheid”). It likely never will in the case of the Security Council until that body is thoroughly revamped, though it is far from the only worthy country excluded from an increasingly archaic club.

India’s “exclusion” from the P5 rankled, especially as rival China did make the cut (though it is unlikely Washington would have insisted that China be admitted had they had the imagination to see what was coming).

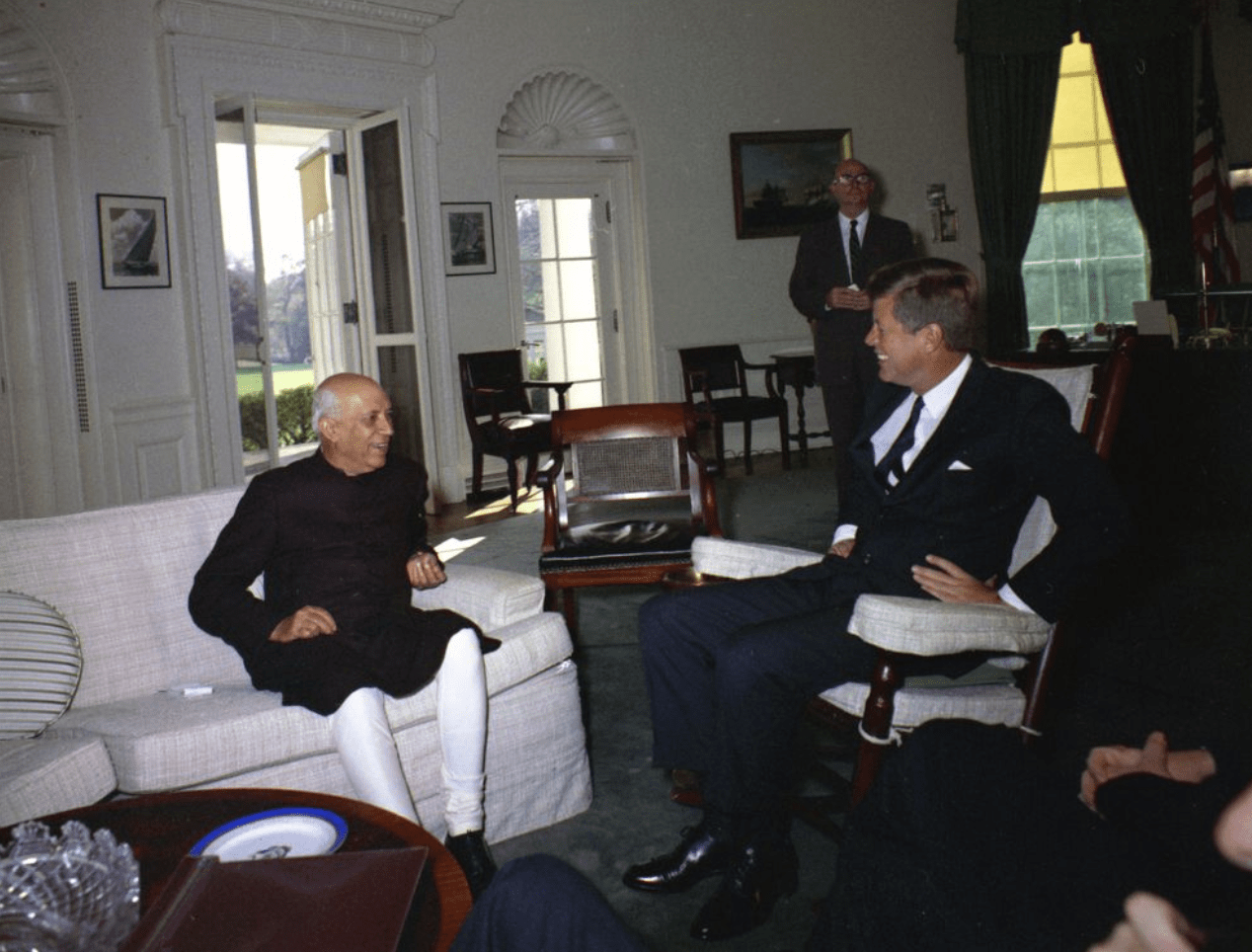

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru with President John F. Kennedy at the White House in 1961/JFK Library

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru with President John F. Kennedy at the White House in 1961/JFK Library

India’s first PM, Jawaharlal Nehru, led the creation of the “non-aligned” movement; countries emerging from colonial status who fought relegation to a supporting role in the Cold War drama. Nehru saw India’s (and his own personal) leadership of that body as the creation of a third bloc in international relations; an alternate route to major power status. Unfortunately, many of the leaders of these countries, though happy to bathe in the rhetoric of non-alignment, were happier to play the Cold War blocs off each other for their own enrichment, if not that of their peoples — a dynamic reflected in today’s geopolitical jostling as political leaders embracing autocracy over democracy reap the benefits of FDI and security protection from China and, to a lesser degree, Russia, at the expense of their own citizens.

India spent the Cold War challenging the rules of the game. On the nuclear issue, it succeeded in doing so in 1974 with its “peaceful nuclear explosion,” or Operation Smiling Buddha, the first nuclear test by Nehru’s daughter, Indira Gandhi, in May of that year. It did not become a fully-fledged nuclear weapon state until it tested actual weapons in 1998.

Freed from the strictures of the Cold War, and those of its own sclerotic economic policies, a renewed India began to emerge in the 1990s. Paul sees this as another moment when India might have mounted a drive to major power status. Unfortunately for Delhi, its main rival, China, was also throwing off the shackles and had a head start. For all India’s impressive accomplishments, China has generally done one, or more, better in the first quarter of this century.

This is beginning to change. India’s population recently passed that of China, which is beginning to suffer very seriously from the decades of its “one child” policy. India’s economy is on track, by some indicators, to catch and even pass China’s by the second half of this century. Could this, then, finally be the beginning of India’s moment to achieve major power status?

In an echo of its Cold War approach, Delhi has pursued friendly relations with Russia — notably via its membership in the BRICs — as a useful counterweight to Western dominance, and an even more useful source of weapons.

Geopolitically, Paul gives India mixed marks on how it has handled its evolution among world powers. After years of chafing at the West’s foreign policy formulation of “Indo/Pak”, which counterintuitively and unproductively lumped the two nuclear rivals together, Delhi has succeeded in getting the great powers to lay that construct to rest and to see India as the key player and Pakistan as a troublesome regional spoiler – though the end of the Cold War and of the West’s involvement in Afghanistan had much to do with Washington’s re-assessment of Islamabad.

Determined to avoid being pigeonholed, and in an echo of its Cold War approach, Delhi has pursued friendly relations with Russia — notably via its membership in the BRICs — as a useful counterweight to Western dominance, and an even more useful source of weapons. But this has placed self-imposed limitations on India’s willingness to take a stand on issues such as Ukraine. This causes the primary power who can “bestow” major power status to question whether, as Paul puts it, India has the power instinct to make hard choices on critical questions.

Paul concludes by examining the cultural/political issues, delving into the Gandhian and Nehruvian Congress Party legacies before examining the rise of Modi and Hindu nationalism. In each of these cases, in different ways at different times, Paul finds that these big ideas have held India back from achieving its major power aspirations. In terms of educating its masses, for example, bureaucratic stultification, an inherent suspicion of the masses by the elites (both inherited from the British) and the pervasive ravages of the caste system led India to quietly invest far less in mass education than did China, with predictable results in social and economic development.

Looking forward, Paul questions whether the “Hindutva” project of Mr. Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), with its grievance politics and anti-Muslim impulses, will, yet again, cause divisions and distractions which will see India slide backwards just as it is on the cusp of greatness.

Overall, this book provides a comprehensive overview and essential analysis of India’s quest to achieve major power status. Paul comes to the view that India’s achievements are significant, but he finds that it is held back by an inability to overcome the impulses of its past. For all of its progress on the tangible, hard aspects of power, the decisive factor is India’s inability to tame the intangibles.

Peter Jones is a professor in the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Ottawa and executive director of the Ottawa Dialogue.