In Love and War: The Resistance Fighters Next Door

By Nahlah Ayed

Penguin Random House/May 2024

Reviewed by Lisa Van Dusen

June 19, 2024

The most iconic, epic wartime love stories share certain qualities: They’re usually fictional; the romantic leads spend some amount of wartime screen-time in the same place; and, in the end, the star-crossed lovers don’t end up together.

In Casablanca, Rick tricks Ilsa into getting on the plane to Lisbon with Victor Laszlo using his hill-of-beans speech; in The English Patient, Katharine Clifton dies in a cave and Count Almasy gallantly crashes the plane containing her corpse; In Doctor Zhivago, Yuri and Lara are separated by the whims of history, he sees her on the street years later and dies on the spot of a broken heart.

The most famous wartime love stories of all are mostly unrequited, thwarted by fate or doomed by context. All may be fair in love and war, but the endings leave a lot to be desired.

Veteran CBC reporter Nahlah Ayed’s The War We Won Apart is about how two secret agents — intrepid English rose Sonya Butt and dashing French-Canadian daredevil Guy d’Artois — survive their hair-raising fates as key players in the French Resistance. It deviates from other dramatic wartime love stories because it really happened, and because the male and female leads live happily ever after, in this case in exotic Quebec.

Ayed’s complete re-telling of a love story that has percolated in various interviews, tributes and D-Day anniversary observances for decades offers a respectful, honest account of two flawed but exceptional people. Indeed, in the wake of this year’s D-Day 80th anniversary, this book serves as a meticulously researched, riveting tribute to all the agents — especially the hundreds of women — whose covert work made the success of the landings on June 6th all the more likely, and whose role as a separate, invisible army is memorialized here. By recounting what these two lived through, she reminds us of what so many others died for.

Sonya Butt (later changed to Sonia, then the nickname Toni) was the product of a British military family divided by divorce, who grew up mostly in France with a mercurial, toxic mother. That made her the perfect, bilingual candidate to transition from her role in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) to the wartime Special Operations Executive (SOE), also known as “Churchill’s secret army” and the “Baker Street irregulars”.

After falling in love with, and marrying, fellow SOE recruit Guy d’Artois during training, she was dropped, at 20, into the French countryside nine days before D-Day. Guy, the son of an Estrie lawyer, had already landed in France, the two having been separated by HQ so that their personal feelings wouldn’t compromise the Resistance if they were captured and tortured in front of each other.

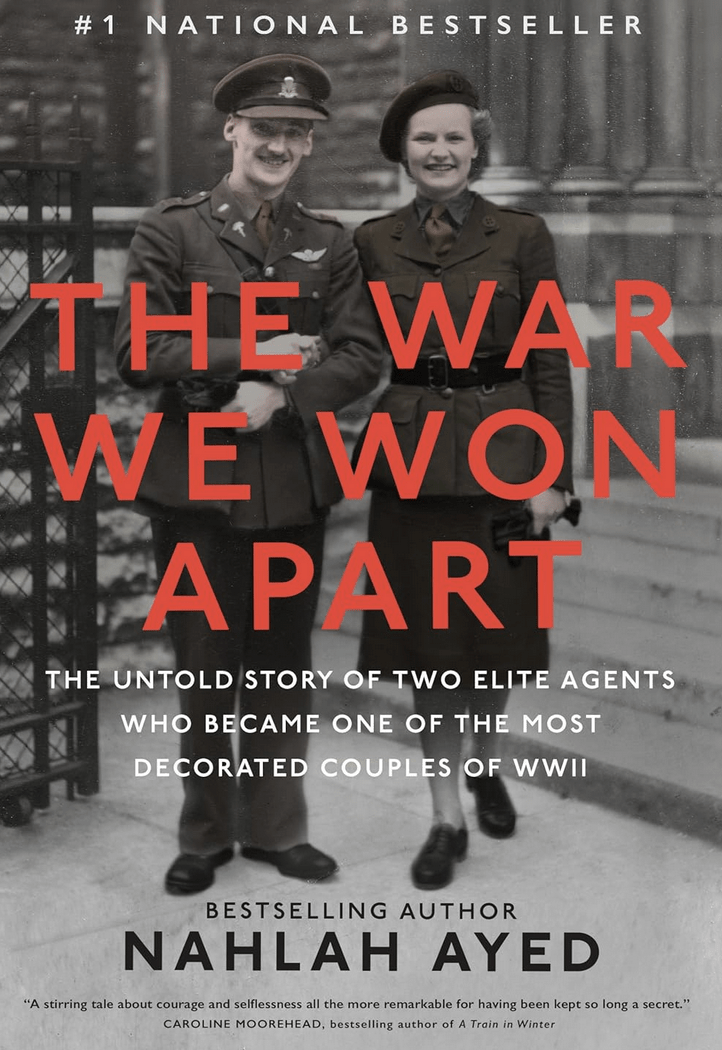

Sonia and Guy d’Artois around the time of their marriage in 1944/d’Artois family

Sonia and Guy d’Artois around the time of their marriage in 1944/d’Artois family

Sonia and Guy then spend the key months of 1944 — from D-Day to the liberation of Paris — apart. Guy becomes the legendary Maquis leader known as “Dieudonné” or “Michel le Canadien”, based in Charolles. Sonia, working 500 km away in Le Mans as a courier and explosives expert, becomes romantically involved with a former SOE suitor who turns up as her superior in their Resistance cell. Again, in wartime love stories, otherwise loyal spouses fall for Humphrey Bogart, Ralph Fiennes, or, in this case, the suave British SOE agent Sydney Hudson. Though also married, Hudson seemed like a fundamentally decent chap and genuinely in love with Sonia, whom he later described as “utterly fearless”.

The War We Won Apart is also about how war disrupts lives by suspending so many of the normal rules and reducing life to a matter of hourly survival — how it adds a whole other level to one’s choice architecture involving existential considerations that would normally not figure into your decisions about where to buy croissants or which cubicle to use in a public restroom based on your need to avoid prowling, murderous Nazis.

But the part of this story that is, in some ways, more interesting than the parachute jumps into occupied territory and the coded messages and the cyanide capsules is what happens when the shooting stops.

Sonia and Guy moved back to Canada after the liberation of Paris, at the end of 1944. He took on a succession of postings in the Canadian Armed Forces and she, after raising their six children, became a retail store manager. In other words, if you happened to have been shopping in a particular Laura Ashley store in Quebec City in the 1980s, that elegant middle-aged woman in pearls who helped you try on a floral sundress could have garrotted you with a hanger in three seconds if you’d asked just one more time to see it in another size. We all contain multitudes.

Sonia, by all accounts including this one, was not a Susan Traherne, the SOE fighter of David Hare’s Plenty who, after the war, is never able to sufficiently disconnect from the adrenaline-soaked, romantic adventurism of her days in the Resistance. With the notable exception of an incident near their post-war home in Hudson, Quebec, when she memorably deployed her SOE combat training on some bullies who were harassing her son, Sonia quietly embraced her new life raising a family, running their household during Guy’s long absences in Korea and elsewhere and eventually, of course, managing a Laura Ashley store without any recorded casualties. This is a survivor story, about two people who not only made it out alive but seemingly did their best to make sure their children would benefit from, not be burdened by, the lessons of their wartime service.

After Guy’s death, Sonia, then in her 70s, and Sydney Hudson were reunited in London, in a surprise (for her) encounter arranged by a British documentarian. The fact that the two then made a pilgrimage to their old field of operations in and around Le Mans accompanied by Hudson’s second wife speaks to Sonia d’Artois’ emotional strength and generosity of spirit — elements of character displayed through her time waging anti-Nazi subterfuge, surviving an SS sexual assault, and making the choice to leave Sydney behind to re-commit to a future with Guy.

So, The War We Won Apart is not a tragedy, although it contains, as all wars do, terrible sadness. Many SOE fighters — including friends and comrades of Guy and Sonia — were killed in action, executed, or died in German concentration camps. More than one-third of female agents and a quarter of the male ones never made it back alive.

Guy d’Artois lived to be 81. He passed away among his fellow servicemen after one final battle, with Alzheimer’s, at the Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue Veterans Hospital in 1999. Sonia died, peacefully, in 2014 at Montreal’s Lakeshore General Hospital. She was 90.

In The War We Won Apart, Nahlah Ayed, with the empathy and insight of a veteran war correspondent, has grippingly captured the events leading up to that relatively, miraculously happy ending.

Policy Magazine Editor and Publisher Lisa Van Dusen has served as a Washington columnist for the Ottawa Citizen and Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News and an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington.