In Both Constitutional and Electoral Politics, Quebec Still Looms Large

To paraphrase Samuel Johnson, nothing induces selective amnesia like the prospect of an election. And to paraphrase Daniel Johnson Sr., Quebec has launched a federal election litmus test on language rights whose signage seems to read, “Unconstitutional if necessary, but not necessarily unconstitutional.” Policy contributing writer and constitutional scholar Stéphanie Chouinard breaks down the political and legal prospects of a revised Official Languages Act and Bill 96.

Stéphanie Chouinard

The first half of 2021 has seen the reopening of an important conversation on a notoriously charged topic in Canada: language rights.

First, the federal government has begun to make good on its promise to revamp the Official Languages Act (OLA), a quasi-constitutional document that has not been thoroughly updated since 1988, when Brian Mulroney was in power in Ottawa. In February, Official Languages Minister Mélanie Joly presented a reform plan aimed at making the OLA more responsive to the needs of official-language minority communities who have, until recently, been the main drivers behind this reform. On June 15, she finally tabled Bill C-32, an Act for the Substantive Equality of French and English and the Strengthening of the Official Languages Act.

Items such as the support of community institutions, enlarging the scope of the Official Language Commissioner’s powers, and reinforcing bilingualism at the Supreme Court of Canada and in the public service were high on the list of priorities of the various minority-community stakeholders. Having voiced the need for an update to the OLA for several years, they seemed generally pleased with the bill. Although this legislative amendment could not possibly be adopted before Parliament breaks for summer recess, the latest federal budget spoke to the government’s ambitions, with some $500 million in supplementary funding announced for official language programs. Notably, close to $200 million was earmarked for the postsecondary sector, this in the midst of a crisis after Laurentian University slashed the majority of its French-language programs and University of Alberta’s Campus Saint-Jean faced yet another series of cuts from the provincial government, bringing the centennial institution to the brink of collapse.

However, Joly’s bill did not stop at the protection of official-language minorities. One of its main goals is, on the minister’s telling, to secure the place of French in Canada—and that includes protecting the language in Quebec. Indeed, socio-demographic data show French is slowly but surely losing importance in the country, even in the one province where it is spoken by the majority. Some of the proposals presented in Joly’s report included supporting French as a language of work in businesses under federal jurisdiction in Quebec.

But in this respect, Joly is facing some competition—from her counterpart in the Quebec National Assembly, Simon Jolin-Barrette. The minister responsible for the French language recently tabled Bill 96, which aims at modernizing Bill 101, notably by creating a French-language commissioner with sweeping investigative powers, making it easier to learn French, and limiting the creation of new English-language spaces in the province’s CÉGEPs. However, even more controversially, Bill 96 also proposes to impose Bill 101 on federally regulated businesses in the province, and to unilaterally modify the Constitution in order to recognize Quebec as a “nation” and French as its “common language”.

Not even in his wildest dreams would Robert Bourassa, in the middle of Canada’s last constitutional upheaval, have imagined such a ploy. For the Legault government, section 45 of the Constitution Act, 1982, according to which “each province may exclusively make laws amending the constitution of the province”, would allow Quebec to go ahead with these changes without the support of the federal government or other provinces. Many legal experts have weighed in, several of them disputing Quebec’s position. What would the recognition of Quebec as a nation mean for Quebec’s “nations within”—that is the Inuit and the First Nations with territorial claims all over the province? How would recognizing French as Quebec’s common language affect the province’s constitutional obligations toward its English-language minority (found, for example, in section 133 of the Constitution Act, 1867)?

These questions remain unanswered for now. The pre-emptive invoking of the notwithstanding clause in the bill is also suspect from a government that promised none of the English-speaking community’s rights would be infringed by the bill.

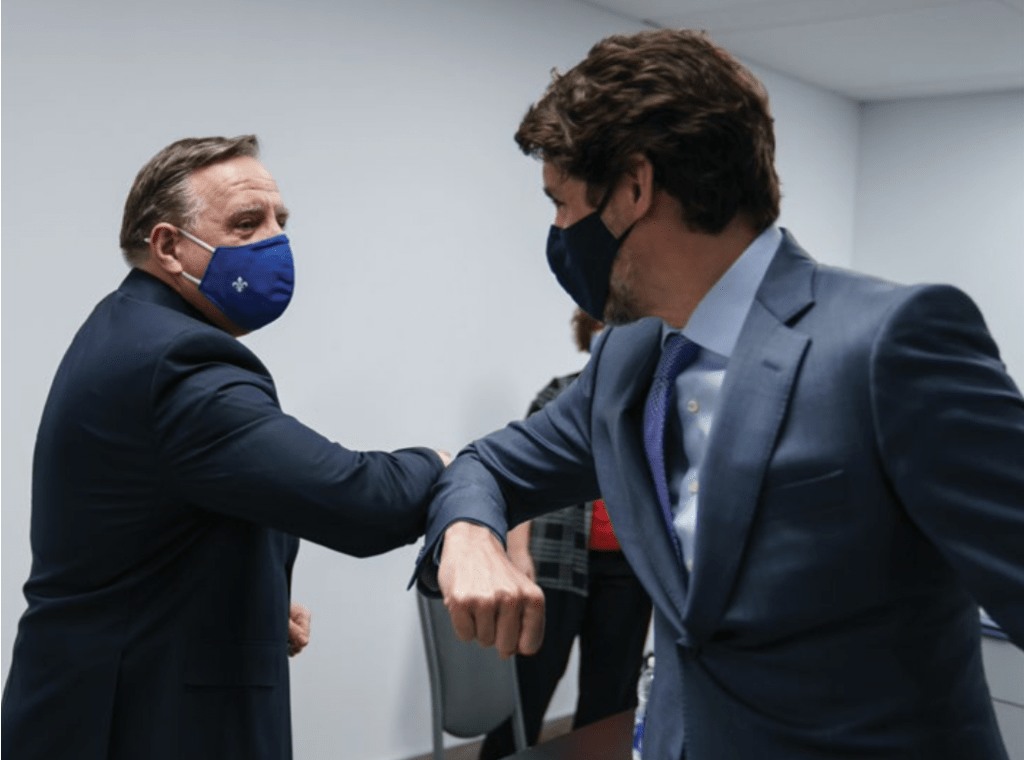

However, when Prime Minister Trudeau himself publicly supported Quebec’s constitutional plan, declaring that both of the elements Quebec wanted to enshrine were self-evident, most were taken by surprise. This would indeed seem a strange stance coming from the same man who, just a few years ago, declared Canada was a “post-national state”.

But from a man with an eye on the next election, which may come as soon as this fall, this statement may not appear so strange.

Indeed, the competition between Ottawa and Quebec City for a place in Quebecers’ hearts—at least the francophone ones—should not surprise us. Playing the identity card has always been up the Coalition Avenir Québec’s sleeve, as is attested not only by Bill 96, but by Bill 21, the Legault government’s far more contentious legislation, which forbids the wearing of religious symbols for almost any public office holder in the province. But while François Legault and his government have been enjoying sky-high levels of popularity for the past year and should not face the electorate for another 16 months, the federal prognosis is much different. The province, and its 78 seats in the House of Commons, are at the heart of both Trudeau’s path to a Liberal majority government and Erin O’Toole’s path to getting the Conservatives back into government. In order to secure these seats, the Liberals are attempting to brand themselves as the “champions of the French language”, while the Conservatives have been trying to seduce Quebec’s right-wing nationalists by making “respect for the country’s two founding nations” one of their key messages.

Both parties have to contend with Yves François Blanchet’s Bloc Québécois, a party that just a decade ago was nearly wiped from the electoral map, standing at just four seats after the NDP’s 2011 “orange wave”. Blanchet, a former senior executive in the province’s music industry who won the Bloc’s leadership race in January 2019, has proven to be a worthwhile opponent, and one who has played with Quebecers’ heartstrings while sometimes acting as Legault’s “megaphone in Ottawa”.

This strategy earned the Bloc 32 seats in the 2019 election, proving it is still a force to be reckoned with. As rumours of an October federal election are growing as fast as the vaccination rates in the country, the table is set for a political showdown, where Quebec’s voters will undoubtedly be heavily courted and bill C-32, introduced too late to be adopted, will most likely find itself in the Liberal platform.

This is not to say that all Quebecers are content with this state of affairs. The province’s sizeable anglophone community are feeling both let down by the federal Liberals’ emphasis on protecting French in their overhaul of the OLA, and worried about the impact Bill 96 will have on the place of English in the province, notably as a language of study and as a language of work. Since the Quebec Liberals have also announced their support of Jolin-Barrette’s proposals, they are finding themselves, for the first time in decades, without a political home in their own province. While they attempt to voice these concerns before both levels of government over the course of the summer, the possibility of a court challenge appears to be a likely option for them to protect their rights.

Contributing Writer Stéphanie Chouinard is an Associate Professor at Royal Military College in Kingston, cross-appointed to Queen’s University, specializing in the Constitution, federalism, minority and Indigenous rights and judicial politics.