Ignatieff Returns to the Great Intellectual Love of His Life: Big Ideas

By Michael Ignatieff

Revised, updated edition from Pushkin Press/May 2023

Reviewed by Bob Rae

June 11, 2023

Early one Monday morning in the fall of 1969, two young Oxford graduate students, Joe Femia and I, made our way to Sir Isaiah Berlin’s office in Wolfson College. We were starting our two-year B Phil degree, which included preparing for exams and writing a thesis. We had both decided to work on Hegel and Marx for the exams to be held in the late spring of 1971. Our Balliol tutor had told us that it was best to throw us into the deep end of the pool “and see who can swim”. That process included regular meetings with Berlin, the renowned liberal philosopher, who was then also president of Wolfson.

Joe, who went on to become a leading political theory scholar, wrote a doctorate (and later a book) on the Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci, for which Berlin would be his supervisor. My own path in life was far more circuitous, as many readers of this magazine will know. I have learned how to swim, thanks in part to times when my head was underwater. Joe and I did pass our exams.

In the late 1960s, there was no central heating at Oxford, and the fall term (known in Oxford parlance as Michaelmas) grew colder and damper as the months proceeded. But a constant source of both light and warmth was our two-hour session with Isaiah. He was welcoming, funny, and, we soon realized, one of the great conversationalists of our time. His breadth of knowledge and his anecdotal recall never ceased to astonish (although we would occasionally hear a story in December that we had first heard in October), and those two hours would keep us going as we struggled our way through Marx and Hegel.

Berlin got us both to write papers every week, and used these as a basis for discussion. It must be said that the virtuoso behind the landmark essay and intellectual party game The Hedgehog and the Fox was not a morning person. After the introductory niceties were concluded, we sat in comfy old chairs near the electric heater. Joe and I were taken aback when Berlin started talking and realized that we had no idea what he was saying. His early-morning voice was like an old car getting warmed up. He spoke quickly, and the words would have flown around the room like bullets had he not swallowed them all. But eventually, the ear adjusted, and I think he slowed down to accommodate the blank faces staring at him. “Ah yes, you want North American speed, I shall do my best to adjust…” He then turned to me.

“Mr. Rae, what is that on the floor between us?”

Long pause as I look down.

“Well, sir that would be a carpet.”

“Very good. Is there anything special about the carpet”?

“Well, it’s very nice, red, and a beautiful design.”

“Anything strike you about the design?”

“I don’t know, kinda symmetrical.”

“Yes, very good, but you’re missing the big point,” he said. “It’s not ‘kinda’ or ‘sorta’ symmetrical. It is perfectly symmetrical. Everything fits. And that’s the big thing you need to know about both Hegel and Marx. They were not men with doubts, or quibbles, or questions. They were men with answers, and they believed in theories that they were convinced explained everything. And as you go through life, you will have to decide whether everything fits, or whether you agree with Kant that ‘from this crooked timber of humanity nothing straight was ever made’.”

That dialogue stayed with me the rest of my life.

Berlin would regale us with the story of writing his own book on Marx (still in print), discovering that Marx had an illegitimate son. At that time, Isaiah was teaching a term at City College of New York, and shared his love of the United States, where he would soon be going to deliver a lecture to the New York Police Department. He was, in short, a phenomenon, but also a gentle, sweet man.

Arlene and I met Berlin again soon after we were married, and I had chosen the path of politics. He was far more interested in talking with her than with me, and he opened up a lot about his family in Latvia and Russia. He asked about our family histories, and gave us a superbly gossipy review of the current political scene. The pace of the flow was just as it had been twelve years before.

My last meeting with Isaiah Berlin was in Toronto, where, in 1994, he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Toronto. I was premier at the time, and he was most generous with his time and sense of the future. He had suffered a stroke in his voice box, and could only talk in the huskiest of whispers. I treasure a photo of the two of us together, which has pride of place in my office.

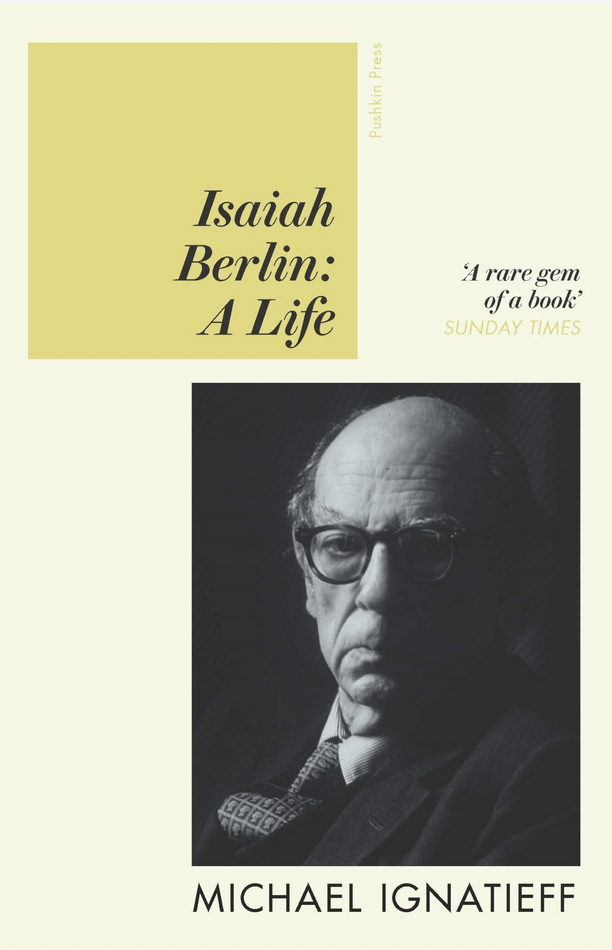

For the many of you familiar with Isaiah Berlin, it’s likely you know about him at least in part from reading Michael Ignatieff’s excellent biography, Isaiah Berlin: A Life. Ignatieff’s revised and updated Berlin book, recently published by Pushkin Press, is at once thoughtful and personal; more comprehensive than the first edition, which appeared in 1998, a year after Berlin’s death. If you have read the first edition, you will still need this version in your library, since it gives such a complete assessment of the man, his thought, and his times.

As many readers know, Michael Ignatieff and I have a long history. We met very briefly as kids when the careers of our diplomat fathers overlapped for a short time in Ottawa. My father Saul and Michael’s father George were students together at Toronto’s Jarvis Collegiate (my dad, an ambassador by way of vaudeville, remembered putting makeup on George for a school show he was directing) and then at the University of Toronto. Michael’s mother Alison was a very close friend of my mother’s, and emotionally close to all of us. When I came to U of T in 1966, Michael and I became classmates and friends, sharing an apartment above a Bloor St. shoe store. We worked together on Teach-Ins and the Varsity Review, and shared many good times together. I later slept on his couch when he was at Harvard studying for his doctorate and I was struggling to figure out my next steps. He was kindness itself during a difficult time in my life. I began law school in Toronto in 1974, and we did not live in the same place again until Michael came back to Canada to run for parliament in 2006. We corresponded, e-mailed, shared meals and jokes, and remained friends. We parted ways over the invasion of Iraq — he was for it, I was against — but visited Kurdish Iraq together in the years afterward.

A nuanced description of the private man, with his love of music and literature, rich friendships and complex romantic life, Ignatieff’s book is also a compelling review of why Berlin mattered, and why he still matters.

Michael’s father had followed Berlin at St Paul’s School and studied with him as a young Rhodes Scholar at Oxford. Their paths had crossed many times, and when Michael became a figure on the London intellectual and literary scene in the 1970s, Berlin and Michael were re-introduced. At Berlin’s request, Michael began interviewing the great man for the book that would eventually become his biography. Over the last twenty years, the Berlin archive at the Bodleian Library has been significantly increased, with masses of personal correspondence gathered, as well as manuscripts republished. Berlin was notorious for his difficulty in putting pen (or typewriter) to paper for publication, and often mumbled that he had never produced a “great book”. He once quipped of a fellow professor, “His every thought is in print.”

Following Michael’s shift to electoral politics in Canada, and then a challenging time as the Rector of Central European University in both Budapest and (thanks to Victor Orban’s personal loathing of George Soros) Vienna, he has now turned his attention back to the great intellectual love of his life; engaging with big ideas, making them intelligible to the general reader, and writing with a vigorous and eloquent style worthy of his subjects.

Michael gives us a picture of Isaiah Berlin different than many of Berlin’s students would ever have known. His father was a Jewish timber merchant in Riga, Latvia, and he maintained a deep love of Russian literature and followed Soviet politics closely. He detested Stalinism. He struggled with feeling an outsider in the English world that he joined as a young teenager after his family fled Russia. This part of Berlin’s life is explored with great depth and sympathy since Michael’s own family — as recounted in his family history The Russian Album — fled Russia after the Revolution (his grandfather was the Minister of Education under the Tsars). While their backgrounds were very different, subject and biographer shared enough to allow Berlin to confide his own turmoil and conflicts. Berlin, as famous for his quotable aphorisms as for his deep thinking, once observed that, “The Jews have too much history and too little geography.”

Berlin did everything he could to fit in to the Oxford of his time, and jousted with linguistic philosophers like Freddy Ayer and J.L. Austin in his role as a don at New College. But it was the war that allowed him to share in the world’s great struggles. He worked for the British Foreign Office in both New York and Washington, and it was there that his passion for people and politics, the feeling of working for a great common project, was put to great use.

Berlin made many friends in Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal administration, and also provided invaluable information on a weekly basis to Churchill and his government. All of us who knew him were lucky to have a tutor who saw there was a wider, consequential world outside political theory, and that leaving the academic life was not always a sign of failure. His own words to me on this subject meant a lot, although it was some time before they sank in.

A nuanced description of the private man, with his love of music and literature, rich friendships and complex romantic life, Ignatieff’s book is also a compelling review of why Berlin mattered, and why he still matters. Isaiah Berlin believed deeply in freedom, privacy, pluralism, history, ideas, learning, and laughter. He despised tyranny, totalitarianism, loose and lazy thinking, and regimentation. He was never boring, and his love of gossip and indiscreet jokes and stories endeared him to all those who were not their subject.

Michael defends Berlin’s actions and thinking at every turn. Berlin used to say that he could not bring himself to deplore the French Revolution, despite its excesses. “In that sense I guess I’m a man of the left.” I used to joke with him that equality and solidarity featured prominently in the revolutionary idea, and I didn’t get the feeling they were as close to him as liberty. He replied, “Sometimes a good quip is terrible politics.” At our last meeting in Toronto, Berlin whispered to me hoarsely that what Britain needed was another “moderate Labour government.” He passed away six months after the election of Tony Blair.

In embracing “freedom from”, or what he called “negative liberty” in his famous inaugural Oxford lecture “The Two Concepts of Liberty” in 1958, Berlin insisted that political tyranny started when those governing in the name of a theory imposed the ways in which people would be allowed to realize their true nature. But short of this, the entire world of modern liberal politics since the mid-nineteenth century has been based on the valid concern that for freedom to be meaningful, it must be more widely shared. Otherwise, we are left in a world where the rich and poor are both free to sleep under bridges — an option that, for some reason, only the poor and destitute avail themselves of. Hence, liberalism requires a strong dose of social democracy. At least that is how I have come to see it in my own intellectual and political journey.

As part of that journey, Michael and I were rivals for the leadership of the Liberal Party in both 2006 and 2008/9, and those contests, predictably enough, did not serve our friendship well. I never felt that the world of electoral and parliamentary politics, which had been my chosen field of battle since 1978, would be one where Michael would feel comfortable, or where his multiple talents and abilities would be treated fairly. Rivalries and competing ambitions within parties take a much heavier toll on friendships than do the battles between political platoons.

But what I know now is that Michael Ignatieff’s continuing contribution to the world of ideas and policy deserves our thanks and respect. He has returned to the world of The Russian Album and Isaiah Berlin, to the ideas of Turgenev and Tolstoy, John Rawls and Ludwig Wittgenstein. Michael has the ability to bring the past to life, and to make intellectual choices clear. He writes and speaks with eloquence, and cuts through difficult material in a way that few other people can. He has fought hard for liberty in difficult circumstances, and has faced political defeat with grace. I am proud to be his friend.

Bob Rae is Canada’s ambassador to the United Nations.