How the National School Food Program Can Make a Difference

Pexels

Pexels

By Clara Geddes

December 9, 2024

These are hard times for incumbent governments. A common explanation for this trend is that prolonged post-COVID inflation left voters feeling financially stretched, with further entrenched inequality amplifying the disconnect from political elites.

The Trudeau government clearly sees the writing on the wall. Down in the polls and facing an election in 2025, they’ve been pushing policies to make life more affordable for the average voter. Some of these initiatives, such as the two-month GST holiday, have been brushed off as pandering. But others could have lasting effects on Canada’s social safety net and are worth taking seriously.

One of these is the National School Food Program (NSFP), which the federal government introduced in Budget 2024 to help families with rising grocery costs. However, the NSFP could mean much more than just short-term financial relief for families. Around the world, school food programs have been shown to improve learning outcomes and deliver lasting economic gains for participating students.

The NSFP is promising, but it’s still very new. If the Liberal government is looking to get credit for supporting kids and families, they’ll need effective implementation to set the program up for success.

Through the NSFP, the federal government will invest $1 billion over the next 5 years by partnering with provinces and territories to deliver school breakfasts, lunches, and snacks. Some of this funding is currently tied up with the Supplementary Estimates B now before Parliament. At this writing, four provinces have already signed agreements with the federal government to receive NSFP funding: Manitoba ($17.2 million over three years); Newfoundland and Labrador ($9.1 million over three years); Ontario ($108.5 million over three years); and PEI ($7.1 million over three years).

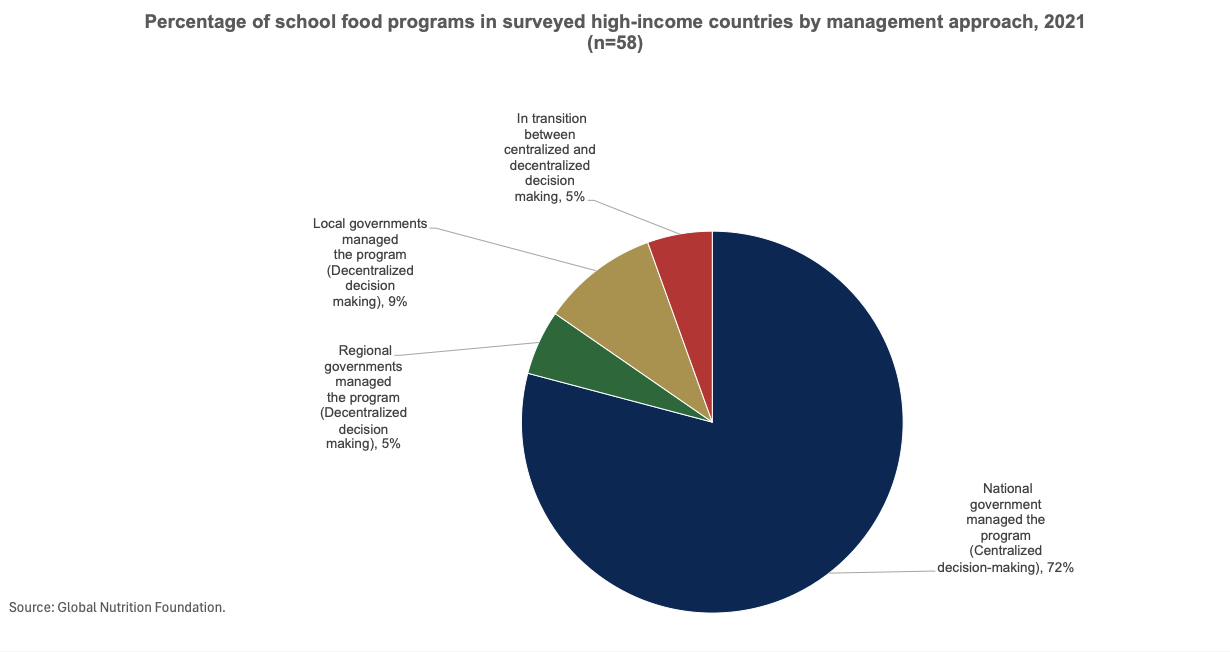

With this funding, the federal government plans to feed 400,000 children who aren’t currently served by a school food program. The NSFP will have a relatively small reach compared to the established, national programs in countries like the U.S. Canada will continue to rely on existing, local programs, which feed an estimated 2 million children a year. (see Chart1). Since the NSFP is so narrow in scope, it should be targeting the areas of highest need. This means looking carefully at who receives meals and what those meals look like.

Chart 1

There are two ways to decide who receives a school meal: means-tested and universal. A means-tested program would only provide free meals for students below a certain income level, whereas under a universal program, any student could request a free meal on a particular day.

The federal government plans to move towards the universal option. This is consistent with best practices. Research suggests students may be hesitant to accept a meal reserved for those from disadvantaged backgrounds in front of their peers. For now, Ottawa isn’t creating a universal program; it is supplementing provincial programs.

The federal government has said they’ll prioritize those facing the “highest barriers to accessing nutritious food” and those “most affected by food insecurity,” including racialized minorities, children with single parents, and remote communities. These are broad and expansive categories. In the interest of transparency, the federal government should track and report to Canadians on what demographics ultimately benefit from the NSFP. This could also allow them to update the program if certain vulnerable populations continue to remain under-served.

In addition to the distribution of federally funded school meals, it will also be worth looking at the meals themselves. Studies have shown that improving the nutritional contents of school meals is associated with better long-term outcomes. The federal government aims to provide school meals consistent with Canada’s Food Guide, but we still know relatively little about whether or how the NSFP will impact the meals that schools currently serve to kids.

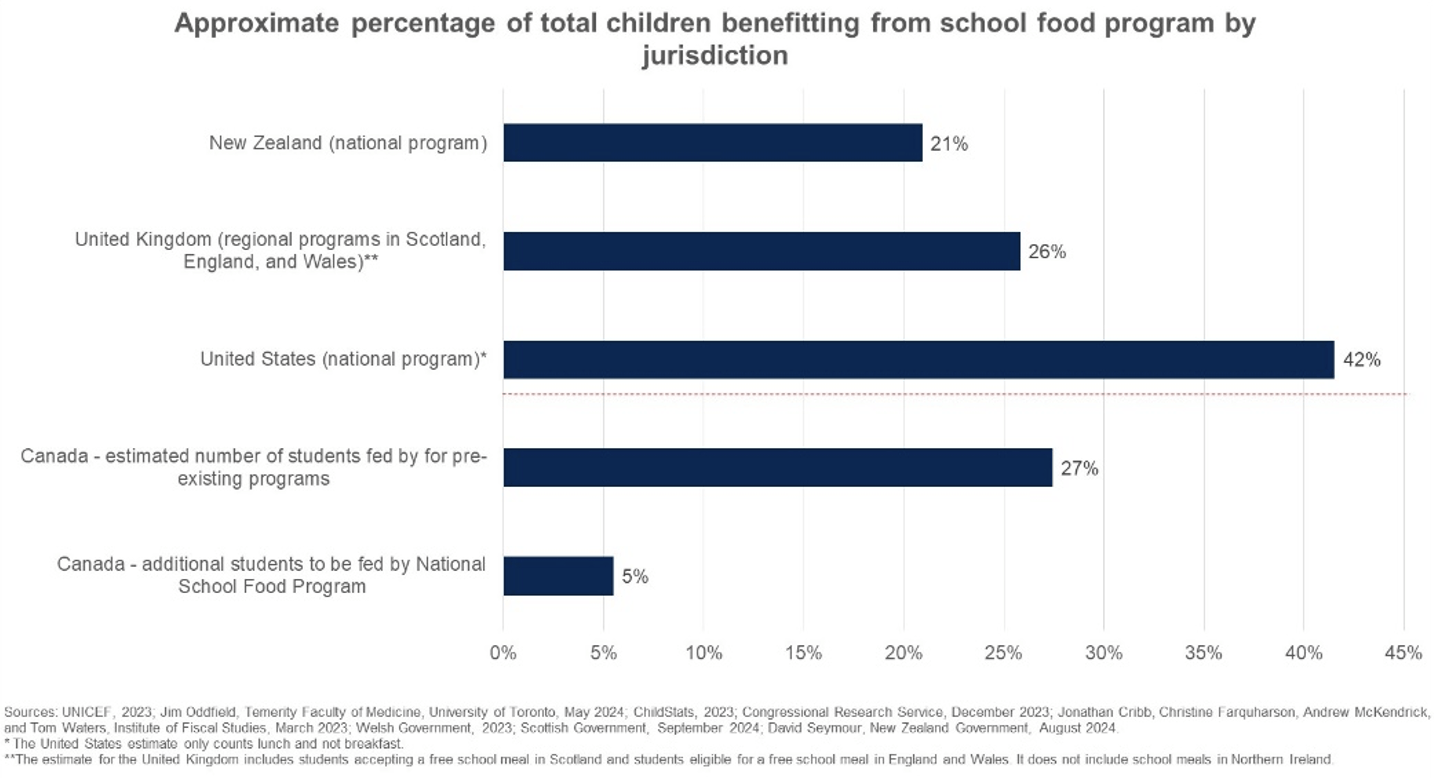

Provincial governments are already responsible for setting and enforcing school meal standards. Although regional governments aren’t usually responsible for managing the school food programs in high-income countries (see Chart 2), it makes sense for the Canadian context since provincial governments are responsible for the public education system.

Even if the federal government isn’t responsible for setting school food standards, they could still provide funding to enhance the meals in existing programs. This is particularly salient in the current economic climate, where Canada’s school food programs have reported that rising costs due to inflation have limited the meals they’re able to offer.

The federal government has started providing funding for infrastructure in existing school food programs. As a complement to the NSFP, they created a $20.2 million school food infrastructure fund for community organizations. And their bilateral agreement with Ontario includes funding for equipment. Outside of these capital expenditures though, we don’t know if the NSFP will address any issues in Canada’s existing school food programs.

Chart 2

The NSFP is meant to provide meals for 400,000 children who aren’t served by an existing program. But are the highest-needs children necessarily the ones not served by any program? Or are they currently being under-served by existing programs?

For example, while existing school food programs serve 2 million children, they tend to offer breakfast and snacks rather than lunch. Even though these kids already receive school food, in the future, we may want to consider whether it would be worth using some of the NSFP funding to add lunches to these programs.

As the NSFP grows and evolves, it’s important for the federal government to work with provincial governments to make sure we track these types of program gaps. Knowing who these programs are feeding and what they’re feeding them is the only way to make sure the NSFP is meeting the needs of Canadian children.

Facing a potential change in government, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has doubled down on his assertion that government can and should spend money to make life better for the middle class. A successful school food program could be a great way to make this point. But that legacy requires solid execution. As the saying goes, the proof of the policy will be in the eating.

Clara Geddes is a senior researcher at the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa.