How a New Bilateral Bromance Could Enhance Climate Action

There may be no issue that better illustrates the shared interests of Canada and our nearest neighbour than the need to address climate change. After four years during which an American president did everything in his power to reverse progress on global warming mitigation, Canada now has a partner it can work with.

Dan Woynillowicz and Eric St. Pierre

In the days following the American presidential election, you could sense a weary (and wary) relief settle in among most Canadians. It had been a challenging four years, to put it mildly, and now there was at least one reason to look forward with some optimism. This sentiment was even more acute among those Canadians concerned about climate change; there was even a sense of ebullience among those of us working to advance climate solutions.

Simply put, Donald Trump’s presidency had been a train wreck for federal climate policy in the US, with the debris field sprawling northward into Canada. Trump had his team scouring for any and every opportunity to roll back and weaken environmental regulations. The result? According to a New York Times analysis, informed by research from Harvard Law School, Columbia Law School and other sources, the Trump administration reversed, revoked and rolled back more than 80 environmental rules and regulations, and 20 rollbacks were still in progress as of November.

Some of those had a direct impact on Canada, such as the weakening of vehicle emission regulations (which are harmonized between our two countries), while others, such as rules to reduce potent methane pollution from the oil and gas sector, bolstered opposition to regulating pollution in Canada on the grounds that it would impact competitiveness.

With the arrival of a US administration that not only accepts the myriad threats posed by a changing climate—to health, the environment, the economy, and security—but aspires to find opportunity in addressing them, Canada once again has an ally and partner. Presuming, of course, that President Joe Biden is as committed to climate action as candidate Biden was.

Biden was a compromise candidate for the Democratic nomination. As the primary started heating up in early 2020, climate action emerged as a key issue among Democratic primary voters and the contenders jockeyed for position. Based in part on his embrace of the Green New Deal, Bernie Sanders briefly topped the polls and took early leads in the Iowa caucuses, where he was edged out by Pete Buttigieg, and in New Hampshire, which he narrowly won. Meanwhile, Jay Inslee, the governor of Washington State, focused his run singularly on climate change, laying out the most comprehensive climate platform conceivable. Kamala Harris laid out a $10 trillion climate plan and played up her credentials as a prosecutor who would target

big polluters.

Meanwhile Biden, the establishment candidate and frontrunner, laid out a moderate approach to climate change that was broadly perceived as a potential drag on his candidacy.

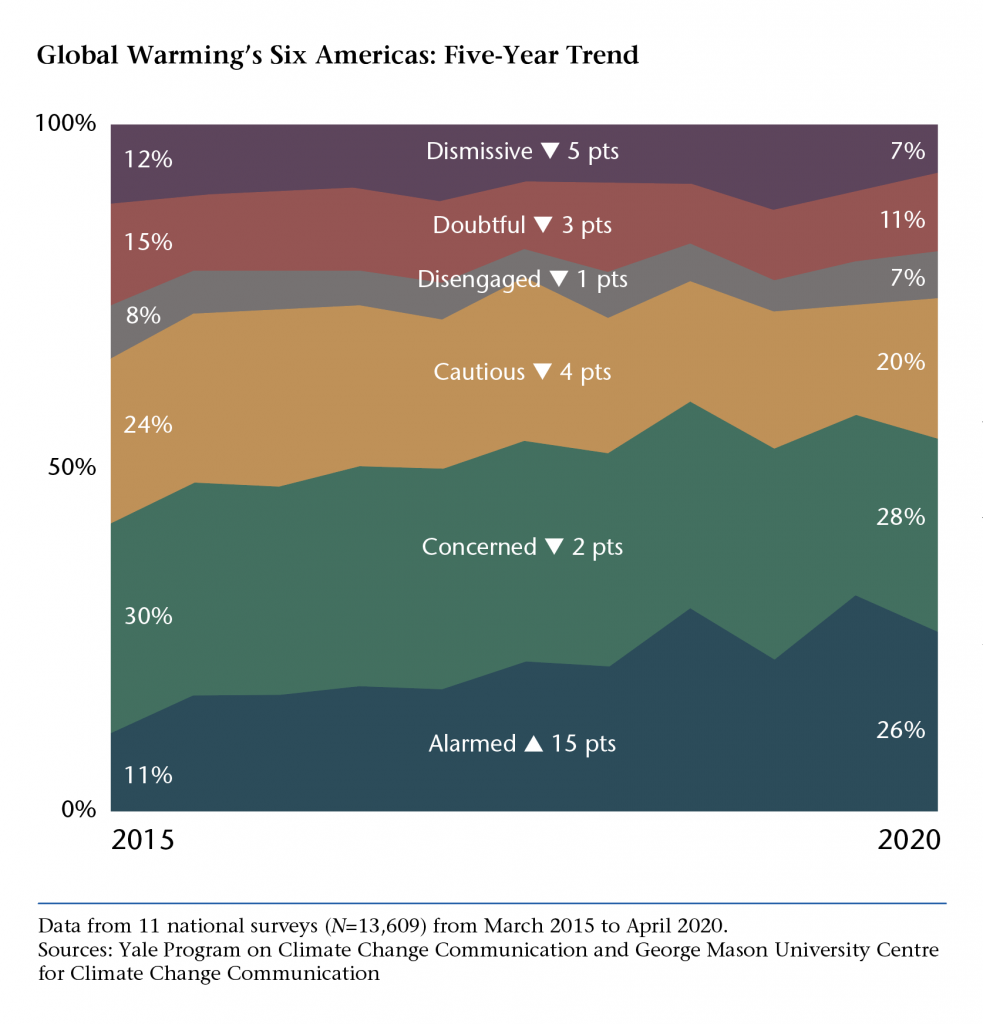

But as the primaries wore on, it became clear that climate change wasn’t just going to be a significant issue for the Democratic base. Opinion research published in April by the Yale Program on Climate Communication, part of an ongoing study of views on climate change dating back to 2008, found a significant shift in public opinion: “Today, the Alarmed (26 percent) outnumber the Dismissive (7 percent) nearly 4 to 1. In 2014, they were tied at 1 to 1. That’s a major shift in the political, social and cultural climate of climate change.”

Similarly, research in May targeting “persuadable voters” conducted by the Global Strategy Group found that, contrary to previous elections, climate change was not a liability but an advantage among swing voters. While not necessarily a top issue for all voters, it was found to be just that for the voters Biden would need to win over in November: young people and persuadable Trump voters.

Similarly, research in May targeting “persuadable voters” conducted by the Global Strategy Group found that, contrary to previous elections, climate change was not a liability but an advantage among swing voters. While not necessarily a top issue for all voters, it was found to be just that for the voters Biden would need to win over in November: young people and persuadable Trump voters.

As it became clear that Biden would be the Democratic nominee, he struck a Unity Task Force. Co-chaired by former Senator and Secretary of State John Kerry and Congresswoman Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez, it merged climate action recommendations from leading House and Senate Democrats, Biden’s primary platform, and a cross-section of civil society climate change and environmental justice advocates, to inform Biden’s platform for the general election.

This approach united his base, expanded his appeal, and informed a soundbite he would repeat numerous times throughout the campaign: “When I hear the words ‘climate change’ I hear another word: ‘jobs.’ We can solve our climate crisis and our economic crisis at the same time.” It was a position that echoed the approach to the post-2008 financial crash recovery, when Biden, as Barack Obama’s vice president, oversaw a recovery program that combined economic stimulus with clean energy innovation.

Biden’s platform included two key planks that wove together his climate, energy and economic ambitions into a plan for a clean energy revolution, environmental justice, modern sustainable infrastructure and an equitable, clean-energy future. With a federal commitment of $2 trillion over four years, Biden laid out a vision and numerous goals, plans and programs to undo Trump’s regulatory rollback spree, re-engage Washington in international climate diplomacy and set the US economy on a trajectory to achieve net zero emissions by 2050.

Polling commissioned by the New York Times just weeks before the vote seemed to prove-out the thesis that climate action could be a vote-winner: 66 percent of respondents were supportive of Biden’s $2 trillion climate plan. In the weeks following the election, it became clear that young Americans had cast ballots in record numbers, playing a key role in handing a victory to Joe Biden, with early research suggesting climate change concerns were a major driver of this turnout.

As President-elect Biden began the transition process, it was abundantly clear he had won a clear climate mandate—and high expectations to go with it.

In the midst of the election the Biden campaign had signalled its interest in appointing a “climate czar” who would drive climate action from the White House. Experience from the Obama administration informed the Biden team of this imperative, and so Obama alumni teamed up with academic experts and former government officials to provide Biden’s transition team with advice on how to deliver on his climate agenda using every department and agency. Unconventionally but wisely, the Climate 21 Project shied away from prescribing policy advice and instead focused on delivering “actionable advice for a rapid-start, whole-of-government climate response coordinated by the White House and accountable to the president,” including memos with recommendations for 11 White House offices, federal departments, and federal agencies, as well as cross-cutting recommendations on personnel and hiring.

Appointments to date suggest that President-elect Biden got the message: John Kerry, who helped forge the Paris Agreement, has been appointed special presidential envoy for climate—now a cabinet-level appointment with a seat on the National Security Council—and asked to help raise global ambition for action. Brian Deese, a brilliant former climate aide to President Obama, has been tapped to lead the National Economic Council. And Janet Yellen, who was chair of the Federal Reserve under President Obama, has been nominated Treasury Secretary, hot on the heels of a stint with former Bank of Canada and Bank of England governor and current UN envoy on climate finance Mark Carney leading the Group of 30, a think tank of former and current policy makers, academics and finance executives exploring how best to shift the global economy toward net zero emissions. It’s clear that Biden means business.

At first blush, all of this is wonderful news for Canada and our climate ambitions, for the federal government especially. There’s some hope that the brief 2015-2017 bromance enjoyed by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and President Barack Obama could be rekindled with President Biden. After all, it was Vice President Biden who visited Canada in the waning days of the Obama administration to urge Trudeau to take up Obama’s progressive torch and there is significant alignment between the two leaders’ climate plans.

But while there is undoubtedly plenty of scope for collaboration, there are also some warning signs that require prompt prioritization by the Trudeau government. All of those climate-action induced jobs and economic benefits Biden promised? He wants them in the US. From zero-emission vehicle manufacturing to producing the batteries that go in them, to advanced biofuels and clean-tech solutions, Biden has “Buy American” on his mind.

Last fall, Canada landed commitments from Ford and Fiat Chrysler Automobiles to re-tool their Canadian assembly plants to produce electric vehicles for the Canadian and American markets alike. We have the ability to produce and export a surplus of clean, renewable power that can help the US achieve its 2035 decarbonization goal. And we’re home to a growing clean tech sector that punches above its weight and whose growth will be fueled by exports to, among other places, the US.

Domestic pipeline politics in general, and Keystone XL in particular, mean that the federal government will need to be seen to champion it with Biden, despite his commitment to rescind permits and cancel the project. But from both a diplomatic and practical perspective, it should hardly be “top of the agenda,” as Foreign Affairs Minister François-Philippe Champagne has vowed it would be.

But we simply can’t afford to get mired in a divisive, and now mostly symbolic, debate about pipelines. The economic and political winds have shifted, and clean energy collaboration and effective climate action must be the top priority.

There is, after all, precedent for doing so. In June 2016, President Obama, Prime Minister Trudeau and Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto established the North American Climate, Clean Energy, and Environment Partnership. But by November 2016 Donald Trump was President-elect, and the partnership was effectively dead.

While it needs to be updated—to reflect the heightened ambition of new net zero targets and new opportunities to develop North American supply chains for batteries, zero emission vehicles and other clean technologies—and may not necessarily include Mexico this time around, this collaborative approach could be coupled with a commitment to keeping the borders open to free-flowing trade.

For the first time ever, we have federal leaders in Ottawa and Washington, DC who have been elected with clear mandates to take action to address the climate crisis. They also now share the challenge of doing so within the context of pandemic-ravaged economies, and, despite majority support, polarized electorates and regional divisions on matters of climate and energy policy.

Prime Minister Trudeau appears primed to this potential. His government’s strengthened climate plan, released in December on the five-year anniversary of the Paris Agreement, noted “there is an opportunity to collaborate with the incoming United States Administration on strong cross-border climate action that can better position the North American economy, as well as Canadian workers and companies so that they can continue to be globally competitive.”

While seizing this opportunity, and tackling this challenge, are better done in collaboration than isolation, the reality is that while President-elect Biden will be a much stronger ally for Canada than Trump was, his first priority will be Americans and the American economy. Canada has managed to carve out exceptions and partnerships to our advantage in the past, and the imperative is that Prime Minister Trudeau do so again—for our environment and our economy.

Dan Woynillowicz is the Principal of Polaris Strategy + Insight, a public policy consulting firm focused on climate change and the energy transition.

Eric St. Pierre is the Executive Director of the Trottier Family Foundation, which supports organizations that work towards the advancement of scientific inquiry, the promotion of education, fostering better health, protecting the environment and mitigating climate change.