He Shoots, He Scores—The Backstory to the Series that Changed Hockey

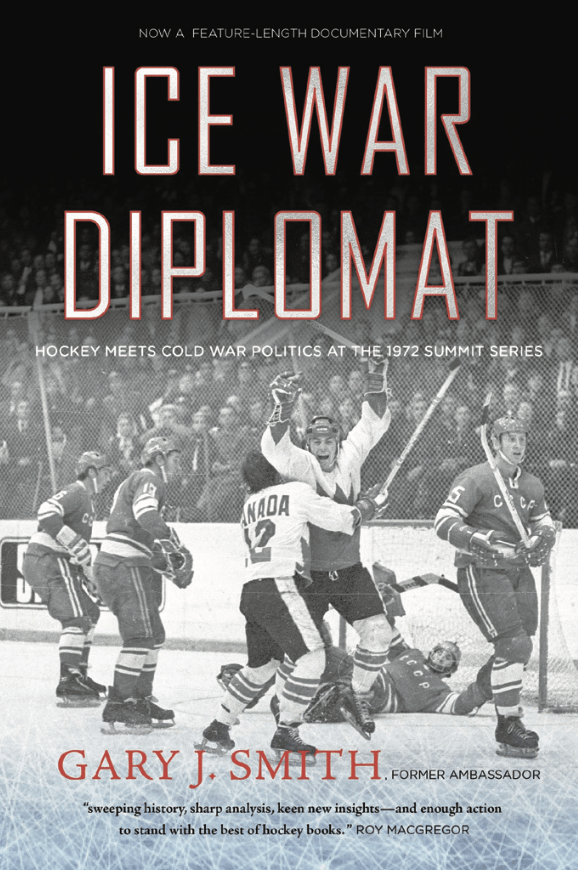

Ice War Diplomat: Hockey Meets Cold War Politics at the 1972 Summit Series

By Gary J. Smith

Douglas & McIntyre, 2022

Review by Paul Deegan

Spoiler alert: we won. Like most Canadians, I have seen or heard Paul Henderson’s: “The Shot Heard Around the World” so many times that I feel like I was there in the stands in Moscow. I can recite the missed pass from Yvan Cournoyer when Henderson was tripped by a Soviet defenceman. I can picture Phil Esposito sending the puck towards Henderson, Vladislav Tretiak’s initial save, and Henderson recovering the rebound and sliding it past Tretiak into the net to give Canada a 6-5 lead with a mere 34 seconds left in the game in what turned out to be the series winning goal.

Gary J. Smith’s new book Ice War Diplomat tells the intriguing story of how the 1972 Summit Series came to be in the middle of the Cold War. To my great surprise, the roots of “Canadian ice hockey” in Russia go back as far as the winter of 1918-1919, when the Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force played in Vladivostok. Their commander organized an eight-team league to keep morale up among his troops. The first organized game in the Soviet Union didn’t take place until 1946. Eight years after that, the Soviets beat us at our own game by winning the World Championships in Stockholm.

Smith begins by astutely putting the bi-lateral relationship in context, “Russia is the only country which makes Canada appear small.” He goes on, “If Canada is said by some historians to suffer from too much geography and not enough history, then Russia suffers from too much of both.”

In May 1969, Smith, a young Canadian diplomat who was just ending his probationary period, was to be assigned to the Canadian embassy in Moscow. After Russian language training in Ottawa, Smith, with his red diplomatic passport, landed in Moscow in 1971. He was quickly recruited for the Moscow Maple Leafs – a team made up largely of Canadians, including a one-time NHL player and the journalist Peter Worthington, but it also included Finns, Swedes, and a Marine from the American embassy as goaltender. They dubbed themselves”Canada’s Greatest Road Team”.

The Canadian Club in the basement of the embassy became a popular watering hole for diplomats from other Western countries. When they drained “Canada dry” of beer, they simply wrote to John “David” Molson, and ordered 1500 cases of Ex and Canadian along with bleu, blanc et rouge jerseys. Molson delivered and the team became the “Moscow Canadiens”.

While Pierre Elliott Trudeau did not play team sports, he enjoyed spectator sports like hockey. He astutely recognized the political value of a dropping a puck at centre ice and the importance of hockey in Canadian culture and identity, and more importantly, in national unity. In the early days, his government quickly set up Hockey Canada, and Trudeau was heavily engaged in proposing that the World Hockey Championships be open to all players – both amateur and professional.

Trudeau’s counterpart, Russian Premier Alexei Kosygin, was also a hockey fan, and he had played the game. During a 1971 trip to Canada, Kosygin faced angry crowds in Canada. In Vancouver, the itinerary called for him to see the hometown Canucks play the Montreal Canadiens. Kosygin was not interested in being booed by 16,000 hockey fans and was going to take a pass. Paul Martin Sr., who was assigned to accompany the premier across Canada, convinced him to attend. He was escorted to centre ice by Henri Richard and Orland Kurtenbach. Kosygin later described his reception at the game as the “the warmest I have received outside my home country.” The light went on for the premier: if the Soviet Union wanted to improve its relationship with Canada, all roads led to hockey.

Against this backdrop, Smith, the diplomat/beer leaguer, and many others established a hockey bridge between Canada and Russia. According to Smith, it is “a bridge which can carry more traffic in the time ahead”. While Smith does not refer specifically to the current prospect of a Russian invasion of Ukraine, he notes, “Engagement and dialogue remain the foundation of diplomacy. Hockey has been, and can again be, part of that process with Russia.”

Canadian painter Kim Dorland’s work was once described as “Like Tom Thomson on Acid”. Similarly, Gary Smith’s Ice War Diplomat is like Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy meets Disney’s Miracle on Ice , with cases of Molson and vodka as the rink boards and KGB spies masquerading as hockey officials. Smith captures the troika of hockey, history, and diplomacy in one fascinating book. We all know the ending, but it’s a long and winding – and sometimes wild – road to Henderson’s goal in this gripping first person account, which promises to delight.

Contributing Writer Paul Deegan is a former public affairs executive at BMO Financial Group and CN Rail (and a Habs fan).