Have Europeans Fallen for the Anti-Democratic Right?

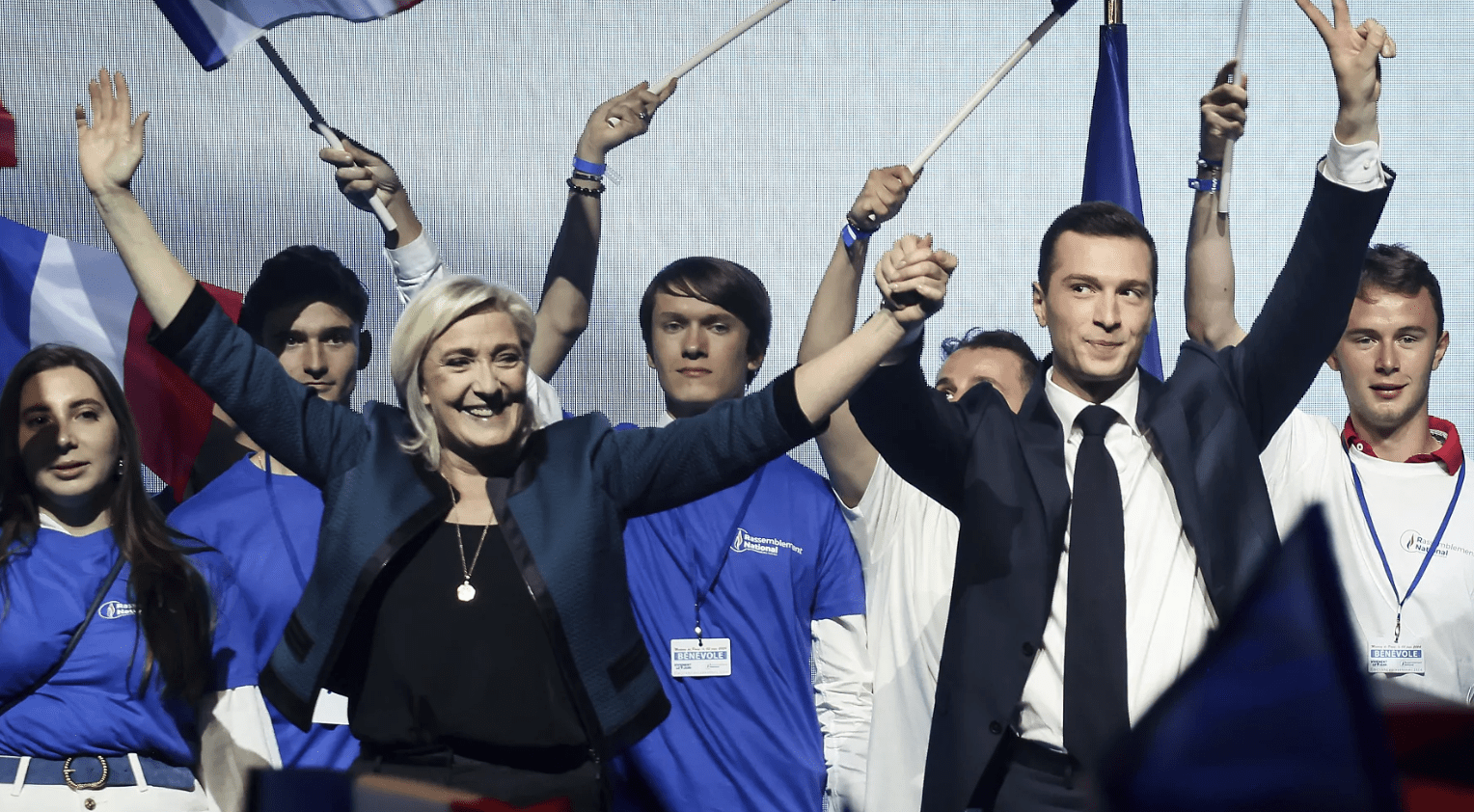

Far-right National Rally Leader Marine Le Pen and party president Jordan Bardella, June 2, 2024 in Paris/AP

Far-right National Rally Leader Marine Le Pen and party president Jordan Bardella, June 2, 2024 in Paris/AP

By Jeremy Kinsman

June 11, 2024

The European Parliament occupies a vast structure in the Euro-land quartier of Brussels. It occupies another one in Strasbourg, France, to which its 720 members and its attendant suite of administrators and ambassadors migrate each year a couple of times at great expense.

Members of the Parliament (MEPs), who are often activists and former government figures, have a pretty comfortable gig, without much to do. No one takes them too seriously. When I was in Brussels years ago, an MEP named Nigel Farage was fronting the UK Independence Party and was more or less a running joke. Live and learn.

The European Parliament has never occupied much of a place in the hearts and minds of EU citizens, who nonetheless vote every five years to renew its membership, in an exercise that makes it the second-largest electoral mass in the world, after India. Its role has always been murky. It has, in recent decades, obtained the right to approve – or not – the EU’s legislation, but without the right to initiate legislation on its own.

EU member states’ own parliaments, and hence, their governments, don’t favour a competitive campaigner for “their” citizens’ votes. But on the other hand, the principal popular criticism of the EU political project has been that the EU is too bureaucratic, permitting technicians to call the shots over citizens’ lives. National politicians love to blame the EU bureaucrats for everything negative. Even though Charles de Gaulle made sure at the European project’s inception almost 70 years ago that fiscal management would remain the sole prerogative of national governments, finance ministers and national leaders have always complained to the public either that “Brussels made me do it,” or that “it’s in Brussels that our economic struggle begins.”

For decades, therefore, elections to the European Parliament have permitted citizens primarily to signal their feelings about the way things are going generally. It’s the perfect occasion for a low-cost protest vote, meant for their own national leaders.

The mood in Europe today, where the economy is tepid, is one of inchoate distaste for politicians, establishments, and “elites.” That mood heralded a surge by the nationalist, rejectionist, right — angry for the same reasons as many Americans: cost of living, immigration, too much woke-ism about gender and inclusion, and, more recently, about the costs of policies addressing climate change.

European Parliament politics are organized through sometimes awkward groupings of like-minded members from left to right. These recent elections are a test of the strength of the far-right in Europe.

I agree with the Globe and Mail’s European sage, Eric Reguly, that in this instance, the “centre held,” but that the far right “broke its fringe status,” and became a mainstream player. Being a protest vote (and turnout was relatively high, more than 50%), some citizens perversely supported rabidly right-wing opponents of immigration or carbon abatement who would struggle to get elected back home. Even in sensible Czech Republic, for example, two MEPs were elected from the overtly fascist Prisaha party (“Oath”) that is formally “extra-parliamentary” altogether, given to Nazi reverence and right-wing disruption shenanigans.

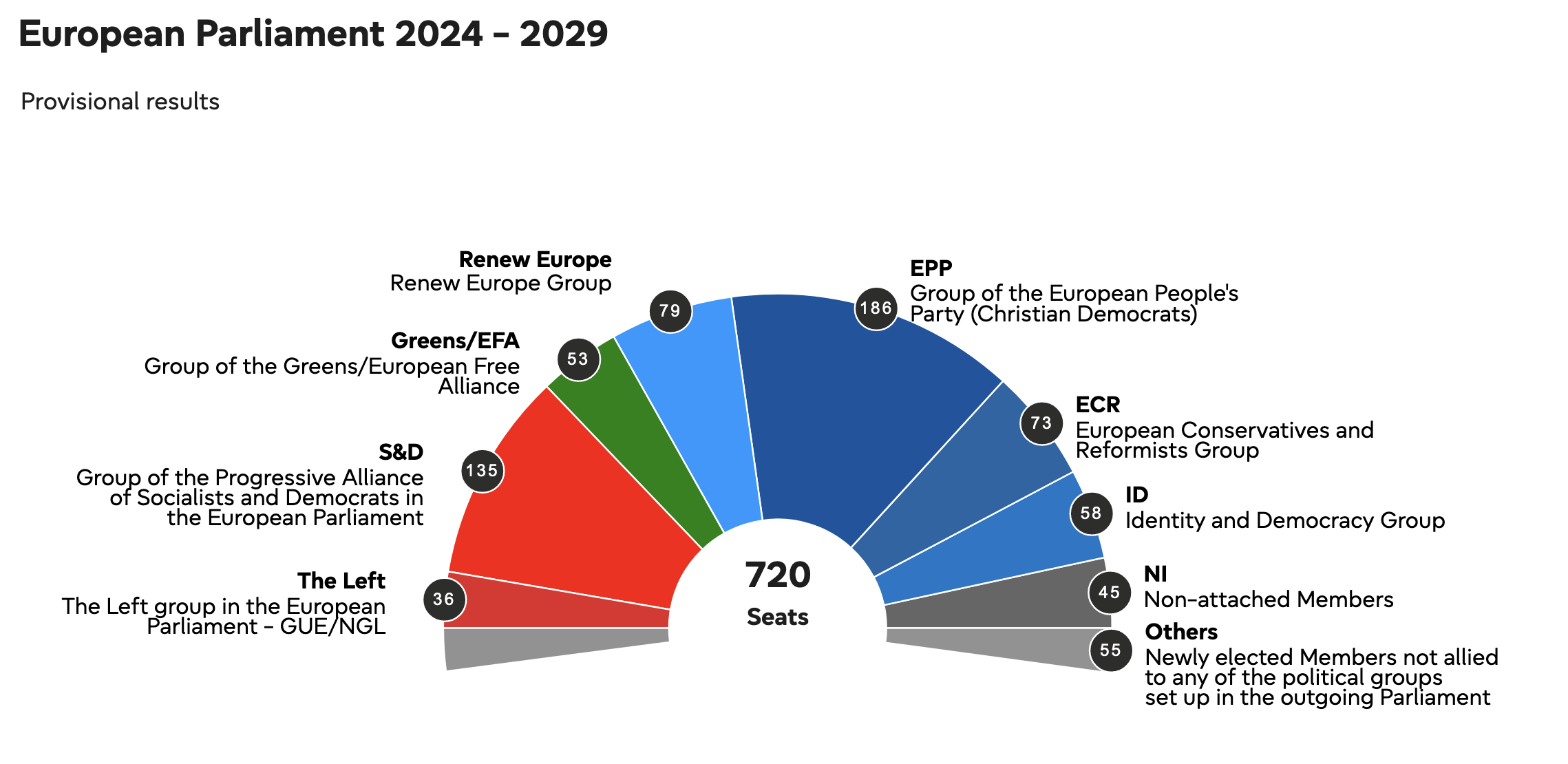

Source: Elections Europa

Source: Elections Europa

While the dominant centre-right grouping (“EPP”) kept its lead majority status in Parliament, the far-right increased its representation enough to make the parliament’s approval of another term for European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen touch-and-go, the math further complicated by European Council President Charles Michel’s overt scheming to prevent von der Leyen from keeping her job. “Member states are increasingly irritated about Charles Michel’s role in the selection process for the Commission President,” one EU diplomat told Politico. “It seems to be driven by purely personal motives.”

The implications for the most prominent European national leaders, especially France and Germany, are dramatic. In France, the very-right wing (though less than before) Rassemblement National, or National Rally party of Marine le Pen — who is expected to have a good chance at winning the presidential elections in 2027 in her fourth attempt — won 31% of the French vote (in a crowded field), double that of President Macron’s Renaissance party.

Macron’s decision to immediately dissolve the French parliament and declare new elections for June 30 and July 7 won’t affect his own tenure, which ends in 2027, but risks him having to appoint a prime minister from the National Rally, another in what the French call a “cohabitation” of rivals. Le Pen’s sidekick, 28-year-old Jordan Bardella, currently the National Rally president, could be that next French prime minister if the party breaks through in the upcoming elections. The political world was astonished at Macron’s audacious move, as if they hadn’t seized even now the extent to which he is a high-stakes gambler, who often wins. After all, he created his own party from nothing in 2017 to sweep elections to the Elysée Palace and then to a majority in parliament, tossing into a dumpster the venerable Socialists, and centre-right Republicans, who, along with the Communists, are from the discredited old world.

Does Macron think that now, at last, the truculent and eternally protesting French voters will face up the truth that, only he, Jupiter, can move French national life to the next (and longed-for) positive level? His self-belief is a force of nature. My own feeling is that he expects Le Pen to win the French election at the end of the month, and her party then to be charged with the reality of office, which in the allocation of duties under the Fifth Republic, awards the PM-designate and government with the hard and dirty work – the economy and the budget, social benefit issues, union protests, health care and education reform, etc. – while Macron can loftily attend to the future of Europe, Ukraine, national security, leaving cuts in the budget to her gang to show the public what to expect from these people (who Le Pen asserts are “the people”, not the “pampered elites in power in Paris today”).

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz is a less self-confident figure. Leader of the the SPD, the German social democrats, Scholz is rated by polls as uninspiring. His coalition government (a necessity in multi-party Germany), with the Green Party, and the Free Democratic Party (FDP) – centre-right semi-libertarian social progressives (more or less) – has been squabbling. The ascendant challenging forces are the revived Christian Democrats on the center-right (more so than under Angela Merkel), solidly in front, but with AFD (Alternative for Germany), a protest party centered in a “left-behind” East Germany that is isolationist and anti-immigrant (and anti-gay, anti-elite, anti-liberal, anti-vax, and anti-Brussels) jumping into second place. Germany’s stature as Europe’s power plant and top dog is now shaky at a crucial time.

Curiously, the leader with enhanced stature is the diminutive but daring Prime Minister of Italy, Georgia Meloni, whose rightist “Brothers of Italy” party (back in the day, pro-Mussolini), made gains, largely at the expense of Greens (again) and the Lega, the formerly dominant right-wing nationalist grouping under the pro-Russian Matteo Salvini, who was trashed. That is good news. PM Meloni has made her government both pro-Brussels (within reason, and a main reason is that EU financing is an Italian necessity), and pro-Ukraine. She remains hostile to EU immigration rules, which keep Italy a catchment for boat migrants, and, as a traditionalist pro-family Catholic, hit an apparent Italian sweet spot, with rejection of woke-ism.

This week, Meloni will host the G-7, whose embattled leaders look at re-election struggles as a potential end of their political rides (don’t even think about poor UK PM Sunak).

They will look at PM Meloni with admiration, and as the proof that Europe will survive all this.

Somehow.

Contributing Writer Jeremy Kinsman served as Canada’s Ambassador to Russia, Italy and the European Union and as High Commissioner to the UK. He is a Distinguished Fellow of the Canadian International Council.