Has Canada Turned the Page on Foreign Policy Passivity?

Like so many things in our 21st-century, post-internet context of geopolitical competition, foreign policy isn’t what it used to be. The fight for domination once manifested in battles over territory and spheres of influence now plays out in narrative warfare on social media screens and in previously unthinkable headlines. Tom Axworthy, who served as a senior advisor to Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, writes that Canada’s foreign policy needs a reboot. Activism over Ukraine may be the spur.

Thomas S. Axworthy

In Policy Magazine in March 2018, former Foreign Affairs Minister John Baird succinctly described the fundamentals of a successful foreign policy: “Foreign policy is about two things: promoting our values and promoting our interests.”

Canadians understand this: a recent (January 2022) comprehensive survey by the Macdonald-Laurier Institute on Canadian attitudes towards foreign policy found that 87 percent of Canadians believe that defending Canadian values, such as democracy and human rights, on the world stage, is important and 85 percent believe that pursuing jobs and economic growth is also critical. Over three quarters (77 percent) also believe it is important to be influential on the world stage, a perspective our political leaders should embrace since foreign policy was almost totally absent from issues debated in the 2019 and 2021 election campaigns.

But the survey also reveals a critical disconnect between mass and informed opinion, a chasm that informs the rest of this article. Sixty-three percent of Canadians believe that Canada is very or moderately influential in world affairs, an increase of 10 percent since 2020. This is a dangerous delusion. If Canadians believe we are influential in the world when we are not, this lets our decision makers off the hook — they can continue to under-invest in the military and development aid, play to domestic voting blocs rather than do the hard work of diplomacy, and be content with government by press release instead of building capabilities.

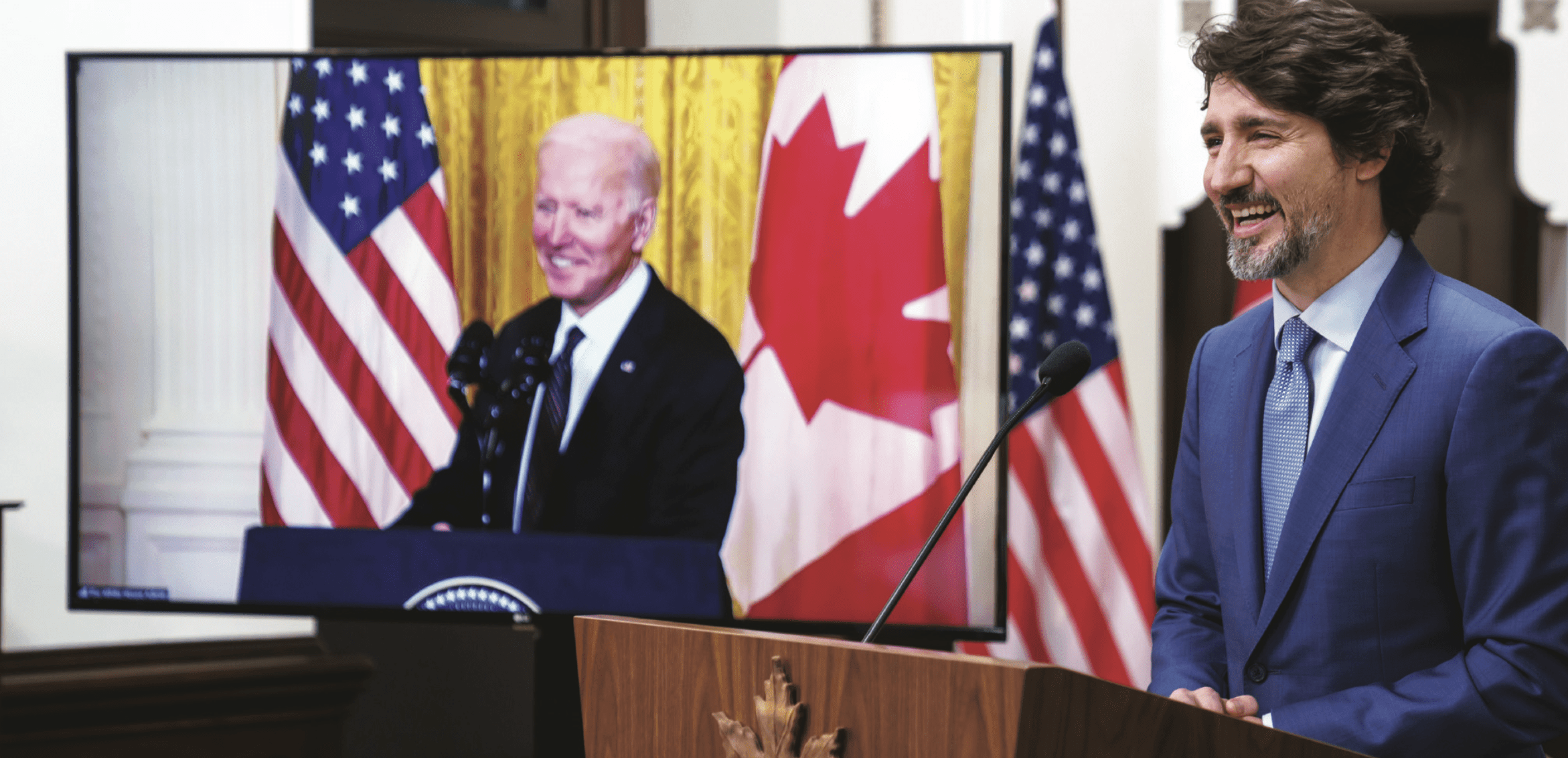

Contrary to the broadly held public view that Canada’s foreign policy influence is strong and even rising, the annual review of the Canadian Foreign Policy Journal gave only a C grade overall to Canadian foreign policy in 2021, with the sub-categories of diplomacy and defence receiving a D+. Looking at results, versus the rhetoric of the Justin Trudeau government, the authors conclude: “This government has failed to provide any strategic guidance on foreign policy since 2015.”

In 2020, Canada failed in its attempt to win election to a UN Security Council rotating seat, which followed a failed attempt of the Harper government in 2010. Prior to the last 20 years, Canada had been elected to the Security Council rotation six times or roughly once a decade under prime ministers St-Laurent, Diefenbaker, Pearson, Trudeau, Mulroney and Chrétien. Unlike Australia, Canada was not asked to join the 15-nation Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership in Asia. Signed in 2020, this pact will create the world’s largest trading zone. Nor was Canada asked to join the United States, Australia and the United Kingdom in 2021 in AUKUS, a new defence pact aimed at containing the growing military might of China. It is abundantly clear that in the realm of world politics and international relations, the phone lines in the PMO, prior to the crisis in Ukraine, had not exactly been ringing off the hook.

It was not always so. In the 50 years of the post-war era after 1945, roughly to the end of the 20th century, Canada was often the first mover in suggesting important initiatives such as NATO by Louis St-Laurent or the Arctic Council by Brian Mulroney. Canada had sufficient military resources to make peacekeeping a reality (and a subsequent vocation) after Lester B. Pearson first suggested the concept in 1956. Under Pierre Trudeau’s leadership, in 1976, Canada was asked to join the G7, the key coordinating body of democratic economic powers. Mulroney’s government negotiated the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement of 1988 and Chrétien’s government initiated the Ottawa treaty on prohibiting the stockpiling and use of landmines.

And it was not only ministers or prime ministers who made a contribution: many Canadian public servants and diplomats were recognized by the world community for their excellence. John Humphrey drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, John Allan Beesley was chair of the drafting committee for the Law of the Sea in the 1970s, and Elizabeth Dowdeswell in the 1980s helped negotiate the Framework Agreement on Climate Change and was subsequently elected to head the United Nations Environment Program.

There have been foreign policy achievements, of course, since 2000: the Harper government negotiated the Canada-EU Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) in 2014 and the current government of Justin Trudeau preserved the NAFTA free trade agreement from the onslaught of Donald Trump, but the record of achievement in the last 20 years looks pretty thin when compared to the highlights of the previous 60.

The main distinguishing feature between the successful foreign policy achievements of 1945-2000 compared to the recent lacklustre record is that the prime ministers of the day understood the realities of the world they had inherited. They adapted Canada’s foreign policies to meet the challenges, they invested in the tools of defence, development and diplomacy to give Canada capabilities to match objectives, and they personally engaged with foreign policy priorities, sometimes even taking large political risks to achieve their goals. The postwar governments of Louis St-Laurent and Lester Pearson understood that the isolationism of Mackenzie King had to go and they created the framework of building international organizations and regimes to bind, or at least influence, the great powers to follow international norms collectively negotiated. They also invested in defence so that as well as launching the idea of NATO, Canada made one of the most significant early deployments to Europe. In 1960, according to the World Bank, Canada was still allocating 4 percent of GDP to military expenditure, by 2020 this had fallen to 1.4 percent.

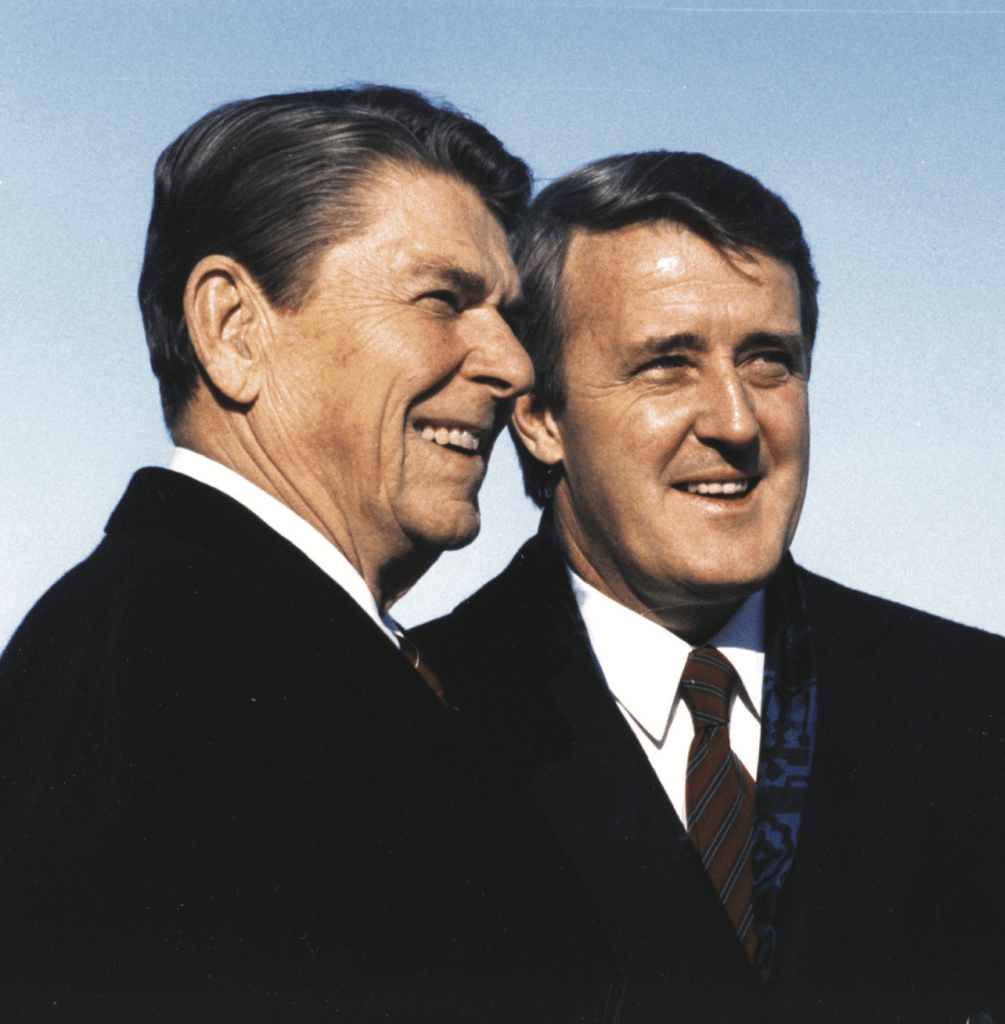

Coming to power in 1968, Pierre Trudeau recognized that the age of colonial empire was over and that countries in Africa, Latin America, and Asia wanted their own voice and independent sway. He began by recognizing the People’s Republic of China. He promoted La Francophonie, created the International Development Research Center, was sympathetic to the Group of 77 developing nations who sought economic fairness with the West and, in 1978, created Operation Lifeline as an initiative to allow private sponsorship of refugees, a first in the world. Trudeau allocated 0.5 percent of GDP to development assistance-today it is only half as large at 0.26. Norway, one of the countries that defeated Canada for a seat on the Security Council in 2020 spends over 1 percent of its GDP on development, Brian Mulroney wanted a robust relationship with the United States and used his notable skills of persuasion to bring this about. James A. Baker, the influential secretary of state for President George H.W., Bush has written: “Brian Mulroney understood that one of the major sources of Canada’s global influence rested on building strong and durable ties with the United States.” The 1987 negotiation of the Canada-US FTA was one result of this influence, but there were lesser-known achievements, too. John Noble, in a 2020 address to the Canadian War Museum, for example, recalled a visit to Ottawa by President Bush, who asked his Canadian hosts for ideas on arms control. Officials came up with the idea of a revamped Open Skies proposal to build trust. When Mulroney raised the idea with Bush in a subsequent meeting at the White House, the President made the proposal his own.

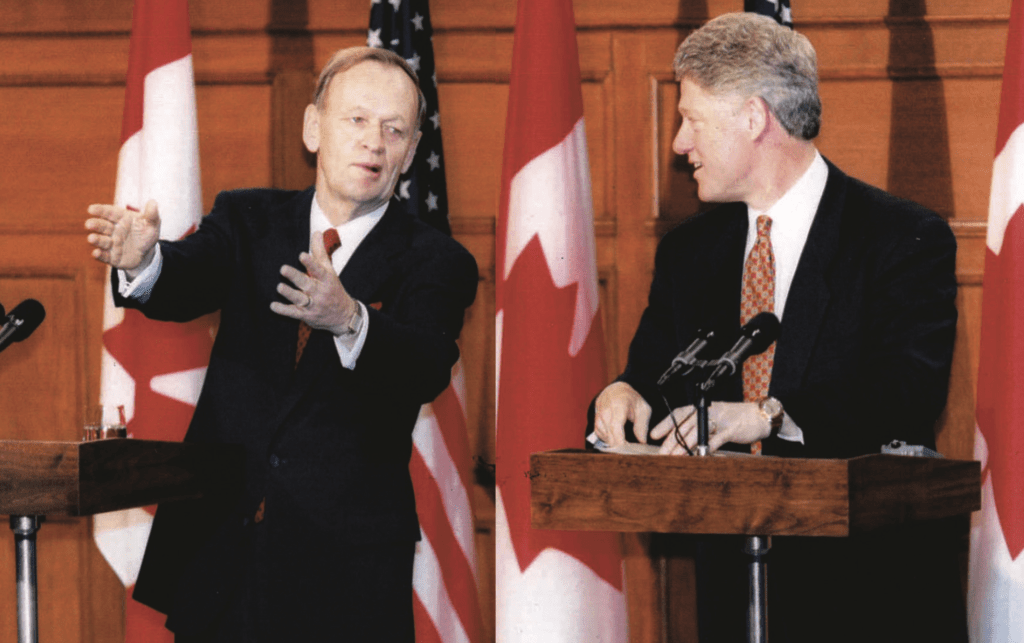

In the 1990s, the world was changing again with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union. It was a hopeful era and the government of Jean Chrétien, urged on by his foreign minister, Lloyd Axworthy, moved with the times. Ottawa proposed a new human security agenda with initiatives on a land mines treaty, support of an International Criminal Court and an ethic of the Responsibility to Protect persecuted peoples even at the expense of traditional state sovereignty. Chrétien and Axworthy took risks in calling for a 1996 Ottawa conference to draft the landmine treaty — the US was opposed and who knew how many states would sign on? The safest course was not to take any chances. But successful prime ministers take risks and when, in December 1996, the UN General assembly adopted a resolution to ban anti-personnel land mines, it had had 115 co-sponsors.

The Land Mines Treaty also shows the centrality of the partnership between the leader of the government and the foreign minister: St-Laurent-Pearson, Trudeau-MacEachen, Mulroney-Clark, Chrétien-Axworthy all complemented each other and brought different skills to the table. The current Trudeau government has had five ministers of foreign affairs in a little over six years. No government serious about foreign policy allows a revolving door to characterize its approach to the management of international relations.

The successful prime ministers were able to take hard assets of power – military strength and economic clout – and use them to achieve results. This, in turn, developed reputation, which is a soft power asset. Canada has enjoyed the reputation of a well-governed, orderly, prosperous, peaceful state which ranks high in human development indexes and is one of the immigration magnets of the world.

This reputation, however, may now be at risk. The recent obstruction of the border with the United States, disruption of supply chains and commandeering of downtown Ottawa, the nation’s capital, by illegal blockades has led to Canada, of all countries, being identified as ground zero for a new form of anti-democracy attack. In Canada today, a truck has become a political weapon.

But recent weeks have seen a burst of government activism: the Trudeau government brought in the Emergencies Act to give police new powers to end the illegal blockades and, no sooner had this crisis ended, another began with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Here the government has been bold and surefooted. Canada not only joined its allies in imposing economic sanctions on Russia and delivering weapons to Ukraine, but it has been a leader in denying airspace to Russian civilian aircraft, calling for the SWIFT transactions system to be added to the economic sanctions and petitioning the International Criminal Court to investigate alleged Russian war crimes.

In defending values and promoting interests internationally, Canadians need a government capable of understanding the world and willing to invest the financial and human resources necessary to build reputation and achieve real results. Preaching from a safe distance is no substitute for such a needed strategy. The war in Ukraine may be a turning point in showing that Canada once again understands this truth.

Contributing Writer Thomas S, Axworthy, Public Policy Chair of Massey College at University of Toronto, was Principal Secretary to Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau from 1981-84.