Green Energy Goals, Red Ink Realities

Robert Kavcic

March 28, 2023

Overview: Food for Fiscal Thought

The 2023 Federal Budget is set against a backdrop of still-elevated inflation, disruption in the global financial sector and a likely looming recession. Despite uncertainty on a number of fronts, and a weaker-than-expected underlying budget balance, Ottawa continues to roll out net new stimulus to the tune of $4.8 billion in FY23/24, and $43 billion over six years. That mostly comes through targeted spending and a swath of tax credits aimed at the clean energy sector. While tax revenues are raised in a few areas and there is some trimming of government operations, the budget deficit sits at $43.0 billion in FY22/23, and about $10 billion per-year deeper through the forecast horizon, with no plan to balance the books. Indeed, the first hint of a balanced budget that we’ve seen in years, which showed up in the Fall Economic Statement for the out-years, lasted all of four months.

It’s notable that the FY23/24 deficit of $40.1 billion is now very much in line with the pre-COVID balance ($39 billion deficit in FY19/20). Over that period, revenues have surged by $120 billion, helped by a strong economic recovery and high inflation. But, program spending has also jumped by $110 billion, even after massive pandemic-era support spending has fallen away. In that sense, there has been some permanence to the jump in government spending that has prevented more fiscal consolidation. To be fair, the average price level in Canada is up about 13% from before the pandemic, and the population has expanded by another 4%, but we’re still seeing program spending hold above pre-COVID norms in real per-capita terms and as a share of GDP.

This budget does a number of things. There are immediate direct household transfers of $2.5 billion, curiously billed as a “grocery rebate” even though groceries have nothing to do with it. This adds to more than $10 billion of “inflation relief” already seen last year at the provincial level. Ottawa is also acknowledging the possibility of recession this year through a stress test of how finances would look in a below-expected economic outlook, which Finance is now making common practice. While the baseline economic assumptions are based on a private-sector consensus, the downside scenario features a recession- like 0.2% decline in real GDP in 2023 that comes with a $47 billion deficit. Finally, on the policy front, there are measures aimed at the clean energy sector in a response to the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act. More money flows into health and dental care, and there are some more tax increases aimed at higher-income Canadians and businesses worth roughly $4 billion annually a few years down the road.

This budget also avoids doing a number of things. Most importantly, large- scale immediate fiscal stimulus is held in check with net new measures weighing at around 0.2% of GDP this year. While inflation has shown signs of cooling, the Bank of Canada remains in a dog fight with price and wage pressures, rendering stimulative measures counterproductive (like direct support payments), although Ottawa just couldn’t fully resist on that front. Oft-rumoured and more contentious policy measures (e.g., broad capital gains inclusion rate, top income tax rate and principal residence exemption) are again unchanged in this budget. All told, this budget continues to push fiscal priorities against a weaker and riskier economic backdrop, leaving behind a deeper deficit path.

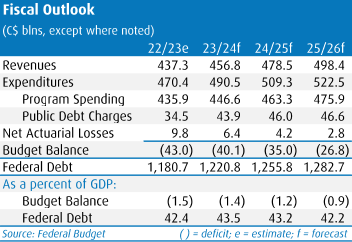

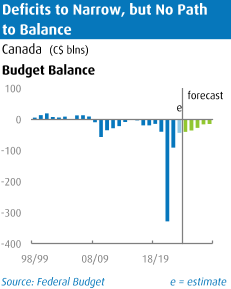

Steady Fiscal Outlook

The budget deficit is pegged at $40.1 billion in FY23/24 (1.4% of GDP), improved slightly from $43 billion in FY22/23. The latter is revised wider from $36.4 billion in the Fall Economic Statement (FES), as increased spending dwarfs a further in-year improvement resulting from the economy. While the deficit is now well down from the record $328 billion at the depth of the pandemic in FY20/21 (thanks to resurgent revenues and expired emergency programs), still-elevated spending, higher interest costs and a downward turn in economic momentum keep the balance in the red through the forecast. Cumulatively, the total deficit between FY22/23 and FY27/28 is now running $69 billion larger than in the FES, split roughly one-third due to economic developments, and two-thirds the result of new measures net of tax increases.

Revenues are projected to rise 4.5% to $457 billion in FY23/24, led by gains in personal income and sales tax receipts. Meantime, program spending is projected to rise 2.5% this fiscal year, with medium-term growth pegged at a similar rate. In the five years pre-COVID, total spending averaged a steady 14.5% of GDP. This year, total spending will run at 15.9% of GDP, before fading to 15.4% late in the forecast. That’s still a noteworthy increase in government spending as a share of the economy, especially at a time of full employment and when nominal output itself has surged on the back of rising prices.

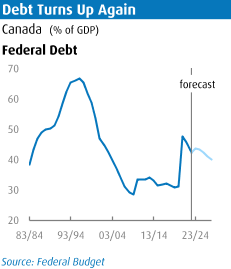

The debt-to-GDP ratio will rise to 43.5% in the coming fiscal year, from 42.4% in FY22/23, before declining gradually to just under 40% by FY27/28. Given that economic momentum is stalling, the major positive surprises of the past two years seem to have run their course.

Whatever Happened to the Fiscal Anchor?

A hard fiscal anchor or even the ‘fiscal guardrails’ set in 2020 had been disposed of well before this budget, probably because they didn’t support the narrative that Ottawa wanted. Let that remind everyone why balanced budget rules, anchors and guardrails, while telling a nice story on Budget Day, rarely hold much water. Ottawa’s guidance last year was “unwinding COVID-19-related deficits and reducing the federal debt-to-GDP ratio over the medium term”. Given that we are back to pre-pandemic levels on the deficit, the downward drift in the debt-to-GDP ratio is now the key major fiscal objective. This budget continues to project a gradual decline over the forecast horizon, but only after a near-1 percentage point increase this coming fiscal year. The issue with this as a fiscal anchor is that the debt-to-GDP ratio is not a hard anchor, and it is usually destined to jump when the economy (the denominator) slows or falls, as is the case this year.

Cloudy Economic Assumptions

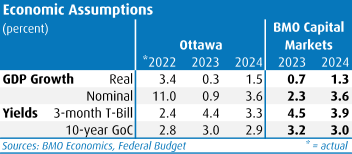

As is the convention, the budget projections are based on the private sector consensus. This round was put in place before turmoil broke out in the global banking sector, which would ordinarily point to immediate downside risk. But, the pre-turmoil consensus was arguably on the conservative side, especially for early-2023 growth. That combination leaves the 2023 growth forecast actually looking a little bit light, but we’re fully aware that this could turn back in a hurry depending on how the situation evolves in coming months.

The budget is based on real GDP growth of 0.3% this year (we are now at 0.7%), and 1.5% next year (1.3%). While real growth gets the focus, nominal growth has been the big story and the driver of revenues. Ottawa expects nominal growth to slow substantially to 0.9% this year after an 11% pop in 2022 (we’re at 2.3%) and pick up to 3.6% in 2024 (3.6%). After a multi-year run of large and persistent upside surprises to nominal GDP and revenues, it looks like the bar has been reset to a much more neutral level. In the downside scenario of a more significant recession (-0.2% real GDP growth this year and muted 1.0% rebound in 2024), the full path of the budget deficit runs about $7 billion deeper per year.

Meantime, interest rates now sit much higher than Ottawa expected along the curve last year. The 10-year yield is pegged at 3.0% this year, while the Bank of Canada is presumed to be finished raising rates. Both of those assumptions are generally consistent with our current view, although we are a bit higher than consensus in 2024.

Debt Management Strategy

With the deficit shrinking slightly, Ottawa’s borrowing requirements will take another small step down. Gross bond issuance is expected to fall to $172 billion, down $13 bln from the prior year. After accounting for maturities, that pegs net issuance at $19 billion. While the issuance figure continues to step down from prior years, keep in mind that the Bank of Canada is still running its quantitative tightening program through balance sheet runoff. In other words, the Bank will have roughly $70 billion of bonds maturing this year, adding to the amount that will need to be taken down by the market. To date, this hasn’t proven to be an issue.

Prior moves in the Debt Management Strategy have extended the term of debt, but issuance in the 10-year and 30-year sectors continues to step down on a relative basis in FY23/24. Planned issuance is $40 billion in the 10-year sector (23% of total) and $10 billion in the 30-year sector (6% of total), versus $52 billion (28%) and $14 billion (8%) respectively in the prior fiscal year. Meantime, 2- and 5-year issuance will see increases, to $76 billion and $40 billion, respectively. That comes alongside a phase- out of the 3-year sector given lower overall issuance needs. Benchmark sizes will increase from last year at the shorter end to absorb the loss of 3-year issuance, while the gradual move away from the long end will reduce benchmark sizes in those areas slightly. Treasury bill issuance is planned to rise to $242 billion. Ottawa will aim to continue the Green Bond program, with issuance dependent on market conditions.

In a surprise announcement, Budget 2023 announced that the Canada Mortgage Bond program is under review to be potentially consolidated into the regular Government of Canada borrowing program. The stated rationale is that it could provide an opportunity to reduce debt charges that can be reinvested into affordable housing programs. There were no additional details, and there will be market consultations over the next six months, with the government reporting back on the potential change at the fall economic and fiscal update.

Appendix: Highlights of Major Measures

The budget contains an array of measures, covering various spending priorities, taxation for higher-income households and corporations, as well as large effort in the area of clean energy. The net additional stimulus amounts to $4.8 billion in FY23/24, or roughly 0.2% of GDP, and $43 billion over six years. Here are some of the most significant measures or proposals:

Affordability measures

GST rebate increase: While billed as a “grocery rebate”, it really has nothing to do with groceries. The GST credit for lower-income Canadians is increased in what amounts to a maximum of $153 per adult. This is an immediate direct cash transfer to lower-income Canadians worth $2.5 billion, with the cost booked in FY22/23.

Student affordability: The Canada Student Grant is lifted by 40%, and the interest-free loan limit is raised modestly. Total relief will amount to $814 million in FY23/24.

RESP withdrawal limit: The withdrawal limit is increased from $5,000 to $8,000 for full-time students, and from $2,500 to $4,000 for part-time students.

Taxation measures

Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) framework: The AMT is a tax calculation run parallel to ordinary income tax rules, with the taxpayer paying whichever amount is higher. Three broad changes include lifting the AMT rate from 15% to 20.5%; raising the basic exemption level from $40k to $173k; and devaluing many exemptions and deductions. This effectively amounts to a tax reduction for a few exposed to the AMT at lower income levels, but a potential tax increase at the higher end (results will vary based on an individual’s mix of income and deductions). Key details inside the new framework include an increase in the capital gains inclusion rate from 80% to 100% for those subject to the AMT. A host of other deductions such as interest charges, moving expenses, child care, as well as most non-refundable tax credits, will be limited to 50%, broadening the AMT base. On balance, these changes lead to a net revenue increase of $150 million in FY23/24, rising to above $700 million by FY26/27.

Global Minimum Tax: Ensures that large multinational corporations are subject to a 15% effective tax rate on profits in the jurisdiction they are operating in, and is consistent with moves made in other countries. This will raise roughly $2.5 billion per year beginning in FY26/27, and has already been planned.

Taxes on financial institutions: This budget changes the tax rate paid on dividends received by financial institutions by treating the flow as ordinary income. Ottawa is expecting roughly $900 million per year from this measure, starting in FY24/25.

Tax on the share buybacks: As previously suggested, a 2% tax on share buybacks will apply to public companies as of January 1, 2024, if those buybacks exceed $1 million. The revenue impact will reach north of $600 million in two years.

Clean economy and response to the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act

The majority of Canada’s focus in this area looks to be coming in the form of tax credits to incentivize investment. The following new/expanded credits come with modest fiscal cost in FY23/24, but rising to more than $5 billion per year by FY26/27. Interestingly, full access to some of these credits is contingent on maintaining a prevailing wage, based on existing union compensation including benefits and pension contributions. At the same time, at least 10% of tradesperson hours will have to be conducted by apprentices.

Clean Electricity Investment Tax Credit: A 15% refundable tax credit on eligible investments (e.g., wind, solar, electricity storage, transmission equipment).

Clean Technology Manufacturing Investment Tax Credit: A 30% refundable tax credit on machinery and equipment in clean technology manufacturing, and to offset the cost of mining and production equipment for critical minerals.

Clean Hydrogen Investment Tax Credit: Credit ranges from 15%-to-40% on project costs related to the production of clean hydrogen.

Clean Technology Investment Tax Credit expansion: The recently-announced 30% refundable rate for those adopting clean technology will expand to include geothermal energy, and the credit will be phased out two years later in 2034.

Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage Tax Credit expansion: The list of allowable expenses under the credit is expanded, and the credit expands to projects in B.C.

Other notable measures

Canadian Dental Care Plan: The dental plan expands to provide coverage for all Canadians with family income below $90k and without insurance. This will be administered by Heath Canada, and cost an additional $2 billion per year by FY24/25 ($1 billion more than previously budgeted).

Details on provincial health transfers: The provinces are receiving an immediate $2 billion top-up the Canada Health Transfer amount, and annual growth is set at a minimum of 5% for the next five years (the formula is normally driven by nominal GDP growth).

Various measures to monitor and limit foreign interference, money laundering and risk in the crypto space. For example, OSFI’s mandate will expand to oversee measures related to limiting foreign interference; and a federal beneficial ownership registry will be created. Amendments to the criminal code will be made to strengthen the AML/ATF regime.

Cost savings: Ottawa will clamp down on internal travel and outsourcing work to consultants. The spending category of professional and special services has more than doubled in the past five years to north of $20 billion. Savings in this area look to run at $7 billion over five years before settling into $1.7 billion per year thereafter. Other departmental spending reduction targets look to cut 3% by FY26/27 for additional ongoing savings of $2.4 billion per year. That said, a good chunk of this ($3 billion per year by FY26/27) was already built into last year’s budget.

Robert Kavcic is director and senior economist at BMO Capital Markets.