Governing for Growth in a Time of Polycrisis

How do governments reconcile the ongoing necessities of fiscal crisis management with the political threat of anti-incumbency? Very carefully.

By Kevin Page with Ali Ghadbawi

November 18, 2024

We live in difficult times for policymakers and governments. The term “polycrisis”, coined by Edgar Morin and Anne Brigitte Kern in their 1999 book, Homeland Earth and revived for our recent era of perpetual disruption by then-European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker in 2018, has now been fully mainstreamed by historians and analysts, including Adam Tooze.

Economics, politics, geopolitics and the natural environment have been in a systemically challenging spiral since the 2008 global financial crisis. Financial Times journalist John Burn-Murdoch calls 2024 “the graveyard of incumbent governments”. Per one truism of economics, “Higher unemployment weakens a government, higher inflation can kill a government.” Or, in the version long applied to authoritarian regimes balancing oppression and stability, “When the people go hungry, governments topple.”

Former central banker Mark Carney was recently named chair of a Leaders’ Task Force on Economic Growth to develop a growth plan that Canada will likely see in Budget 2025. The challenge of both the scope and rapidly evolving nature of managing economic growth amid a world in polycrisis – including the pandemics, supply chain vulnerabilities, global inflation, political upheaval and geopolitical competition that make the economic status quo such a moving target – is evidenced by the fact that Carney’s is the second such assignment in a decade. The first was then-Finance Minister Bill Morneau’s Advisory Council on Economic Growth, chaired by another Canadian international financial player, McKinsey Global Managing Director Dominic Barton.

Is this the time for elected, Western governments to shift the focus from affordability to growth and productivity (inclusive and sustainable)? Yes. Canada is losing significant economic space to our competitors, namely the US. There is urgency.

Is this a natural policy shift for governments? No. Price levels are high. Policy pressures are numerous. Political tensions are high. Trust and confidence are low. Growth agendas involve longer term timeframes, collaborations, capital investments and structural policy changes (i.e., regulations). There is no low- hanging fruit for political leaders and the private sector.

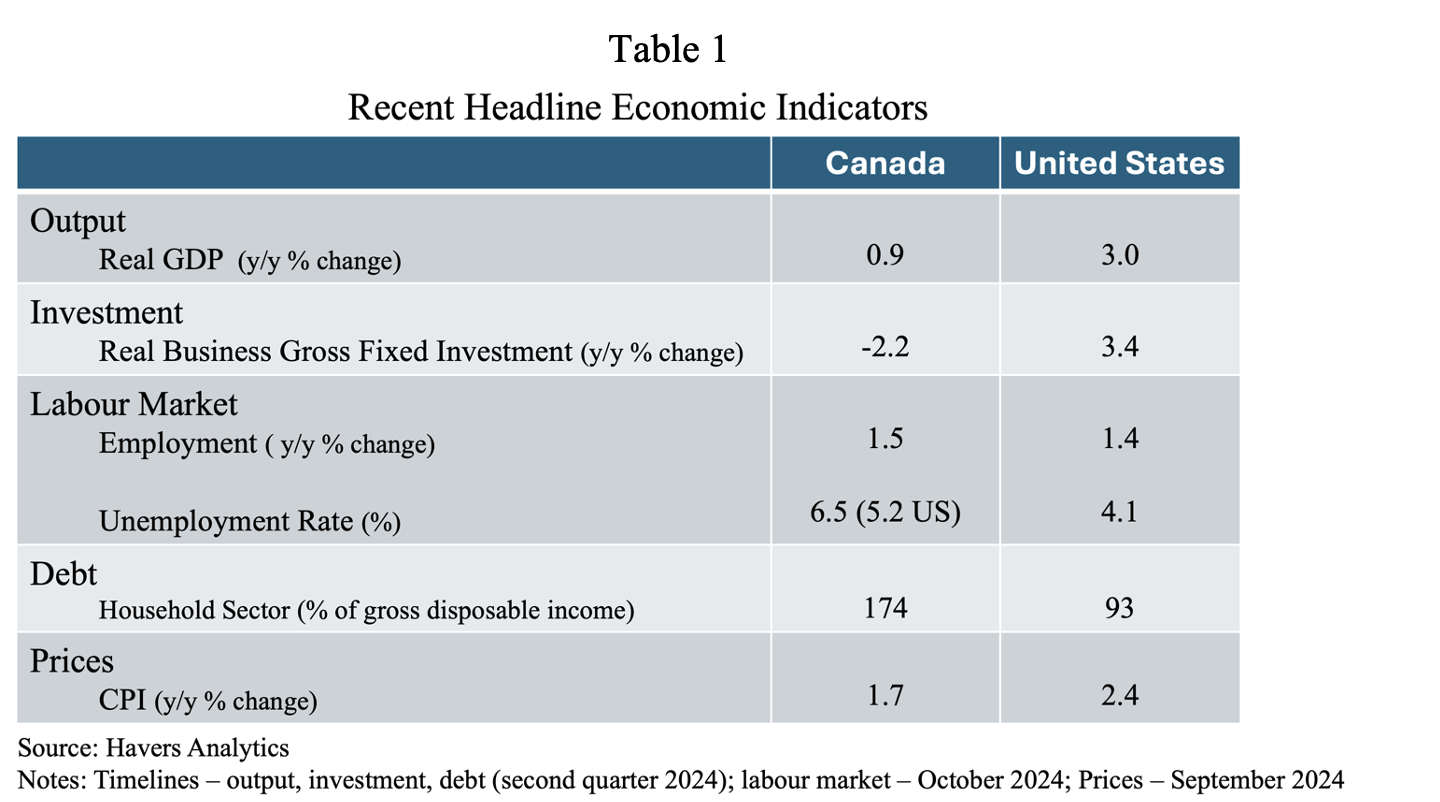

Table 1 highlights some current economic performance gaps. While both Canada and US are seeing a return to modest inflation rates and are experiencing employment growth (good news), Canada is losing badly on growth and investment. On a year-over-year basis, Canada is growing at one-third the pace of the US. The weak growth rate in Canada includes the recent technical adjustments made by Statistics Canada which increased the level of GDP. Real business investment is growing in the US and shrinking in Canada. Reflecting higher labour-force growth and weaker output, Canada’s unemployment rate is a full percentage point higher (on a US comparable basis). Canada is loaded down with high household debt.

Canada needs lower interest rates and growth to lighten the debt load. Canada needs growth to generate budget revenues to pay for new progressive policies (e.g., children, dental, pharmacare).

Chart 1

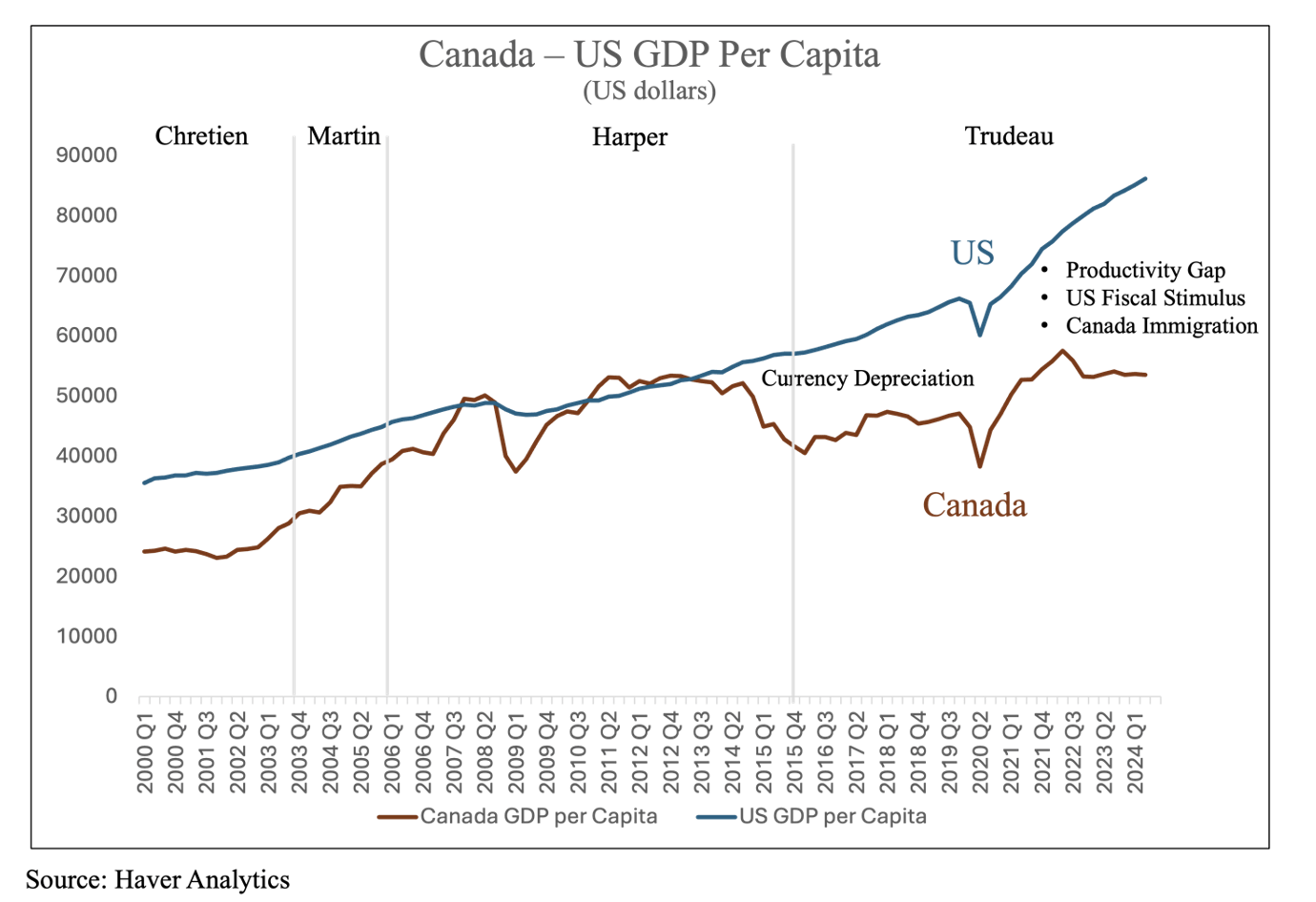

Most Canadians have a sense that we are gradually but significantly becoming the less well-off neighbours to the north. We travel south. We watch and read the news. Could it be that income growth for Canadians, not inflation, will be the next curse that sends future governments to the graveyard?

Chart 1 shows the sizeable average income gap (GDP per capita; US dollars) in 2024 – $86,000 in the US vs $53,000 in Canada. While Canada can make claim to a strong social safety net; better health indicators; and more equitable distribution of income and wealth – $33,000 per capita is significant money. It is a noticeable gap that has widened over the Harper and Trudeau governments.

To be fair, income gaps with the US are widening with most OECD countries. Ironically, it is happening at a time when the US electorate voted an incumbent government out of office, in part, because of the perception of poor economic performance and higher prices, two weeks after an Economist cover dubbed the US economy The Envy of the World.

Why has the income gap grown so significantly since the 2008 global financial crisis?

One factor is currency depreciation. The Canadian dollar is down more than 25 percent since it reached parity with the US just before the 2008 financial crisis. Warning. The late US businessman and political figure Ross Perot said “A weak currency is a sign of a weak economy. A weak economy leads to a weak nation.”

A second factor is fiscal policy. Federal budgetary deficits in the US are about 6.5 percent of GDP, compared to less than 2 percent of GDP in Canada. The Canadian economy would be growing much faster if we added the equivalent of 4.5 percentage of GDP ($140 billion) of deficit-financed fiscal stimulus to our $3 trillion economy. US fiscal policy is not sustainable. In time, market and political pressures will push for greater fiscal responsibility in the US – likely driven by the impact of higher interest costs on the public debt.

A third factor is the recent high population growth in Canada. It is skewing comparisons of GDP per capita. In Canada, population growth is up 3 percent on a year over year basis, compared to only 0.5 percent in the US. This comparison will change with the recent policy reset in Canadian immigration policy and prospects for illegal immigrant deportation in the US under the new Trump administration.

The fourth factor is productivity. Canada is losing ground to the US on productivity. This is a key measure of Canada’s capacity to generate value-added output relative to the size and quality of the labour force and capital investments. Economic history tells us that productivity is linked to the capacity of economies to innovate to deliver better quality goods and services for citizens through the use of new technologies and more efficient ways of working. Economies grow by increasing labour and capital inputs and/or becoming more productive.

Over much of the post-world war period, the Canadian and US economies grew in tandem as seen in similar output and employment trends. From 1960 to 2000, both countries experienced similar labour productivity growth rates of about 2.3 percent. Post-2000, however, a persistent productivity gap emerged – with average annual US labour productivity increasing at more than double the Canadian rate (2.1 vs 0.9 percent). This has resulted in relatively higher US growth and per capita incomes.

Chart 2

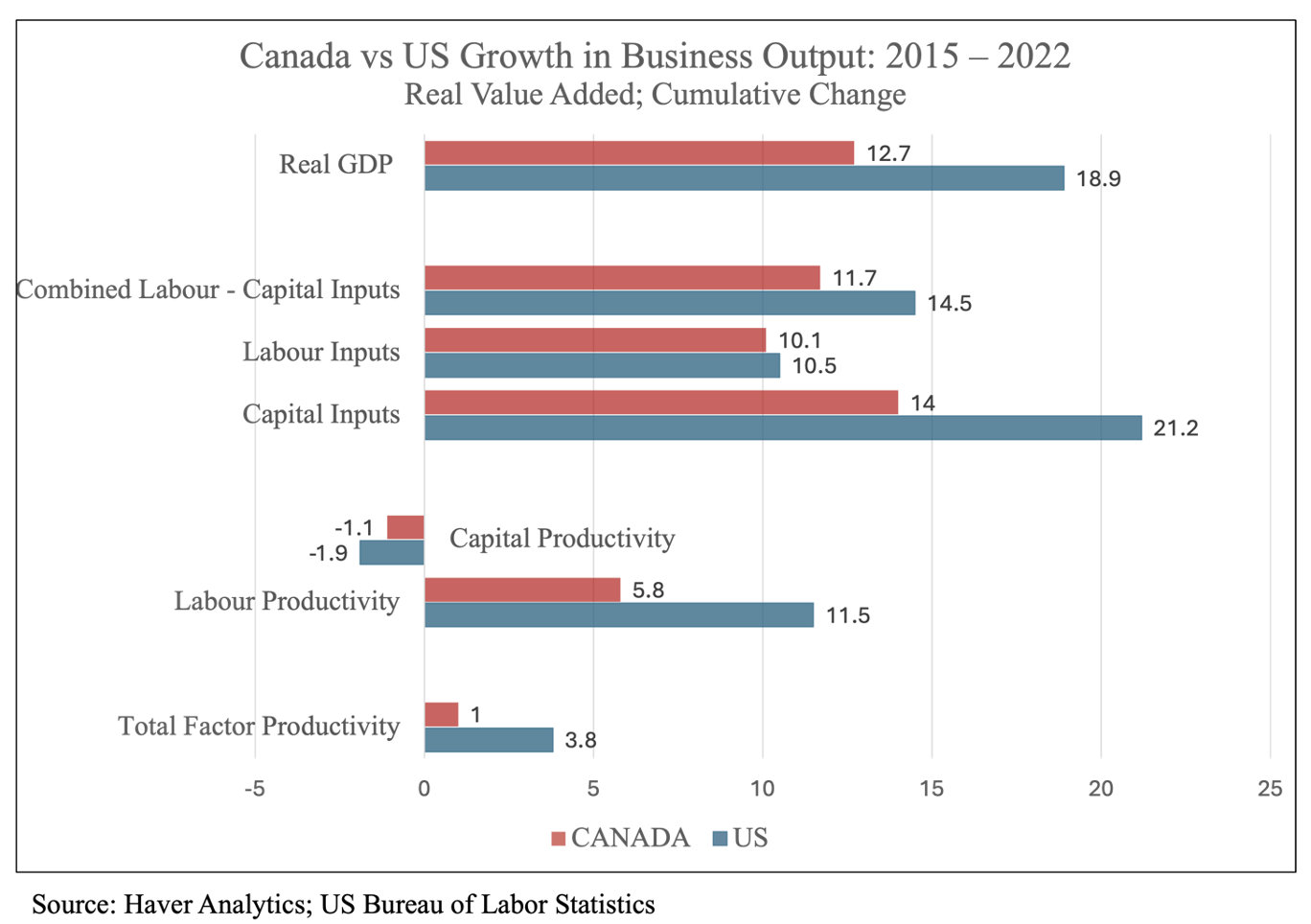

Chart 2 deconstructs Canada and US economic performance over the 2015 to 2022 period from a growth and productivity perspective (i.e., much of the current Liberal government time span) using public data from Statistics Canada and the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Value-added real business output in the US grew much faster than Canada (18.9 percent vs 12.7 percent).

From a productivity perspective, there are a few signature highlights. One: the US has made significant capital investments in technology and infrastructure, spurred on, in part, by the US Inflation Reduction Act. Long-term sustainable growth requires investment in capital and workers. Two: US labour productivity growth has maintained a pace roughly double that of Canada’s. Three: total factor productivity, reflecting the synergies between labour and capital investments, is running much faster in the US.

The context for a shift to a more pro-growth and productivity agenda has started.

Widespread political and business concerns about a future Trump administration with an “America First” agenda that includes tax reductions, deregulation, tariffs and deportations has elevated the sense of urgency for a plan on growth and productivity.

Canada’s leading think tank on productivity, the Canadian Centre for Living Standards, has provided excellent independent research on the policy challenge .

Bank of Canada Governor Tiff Macklem, his predecessors, and business leaders have all called for more investment in priority areas (spending on research and development is well behind OECD averages) that will increase productivity as well as for reforms to improve business growth, regulation and technology adoption.

Canada’s competitors have growth priorities, strategies and fiscal policies that could be adapted to inform and shape an agenda for Canada. While many of Canada’s productivity challenges are homegrown (e.g., inter-provincial trade barriers), best practices elsewhere can be adapted for setting priorities, targets and allocating capital investments:

The Mario Draghi European Union 2024 study on competitiveness focuses on economic challenges created by the US and China and calls for significant new investments (750-800 billion euros annually) targeted to designated key areas – energy, artificial intelligence and pharma.

Prior to COVID, Germany launched Industrie 4.0 to help manufacturers integrate the latest developments in digital technologies into their production methods. Germany ranks 4th in the Global Competitive index. Canada ranks 14th.

Finland’s national agenda emphasizes innovation and sustainability. Finland has targeted 4 percent of GDP on research and development by 2030 (Canada is current spending 1.9 percent). Finland ranks 7th in the 2024 Global Innovation Index. Canada ranks 14th.

The US Inflation Reduction Act was launched in August 2022. It enhanced or created more than 20 tax credits for clean energy and manufacturing. In the second quarter of 2024, US real business fixed investment was up 3.4 percent on a year-over-year basis in the second quarter of 2024. In Canada, real business fixed investment shrank 2.2 percent.

China aims to lead globally in green technology. Between 2016 and 2020, China invested over $440 billion in renewable infrastructure, making it the world’s largest investor in solar, wind and hydroelectric power. It has targeted 40 percent of its news cars to be sold by 2030 as electric vehicles. China now accounts for 30 percent of the world’s renewable energy capacity (2022) and in 2023, nearly 60 percent of new electric vehicle registrations were in China.

A new Canadian plan for growth and productivity should be informed by an evaluation of the strengths and weaknesses of Canada’s current plans, policies and investments. The policy foundations of the Liberal government go back to the 2017 Canadian budget with a focus on strengthening the middle class, innovation and long-term productivity.

The time has come for a new focus on growth and productivity. Canada is playing a catch-up game. We have lost economic ground to the US – a trend that is likely to persist if we do not prepare for an America First agenda. Global trade wars are not good for growth. Canada’s global competitors are making large strategic investments to keep pace with the US and China. Canada needs a plan. It will require significant resources and collaboration across sectors.

Jean Claude Juncker famously said, “We all know what to do, but we don’t know how to get re-elected once we’ve done it”. The antidote to the virus that sends incumbent governments to the graveyard is likely consultation and performance. Canadians need to be involved in the development and implementation of a new growth plan. They have skin in the game. It will take time.

A federal election is scheduled for next year but could come sooner than October. Political platforms of all parties will be under pressure to develop priorities to increase growth and productivity. The policy pivot must happen – from affordability to growth; from consumption to investment.

Ali Ghadbawi is a fourth-year economics student at the University of Ottawa.

Kevin Page is the President of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa, former Parliamentary Budget Officer and a contributing writer for Policy Magazine.