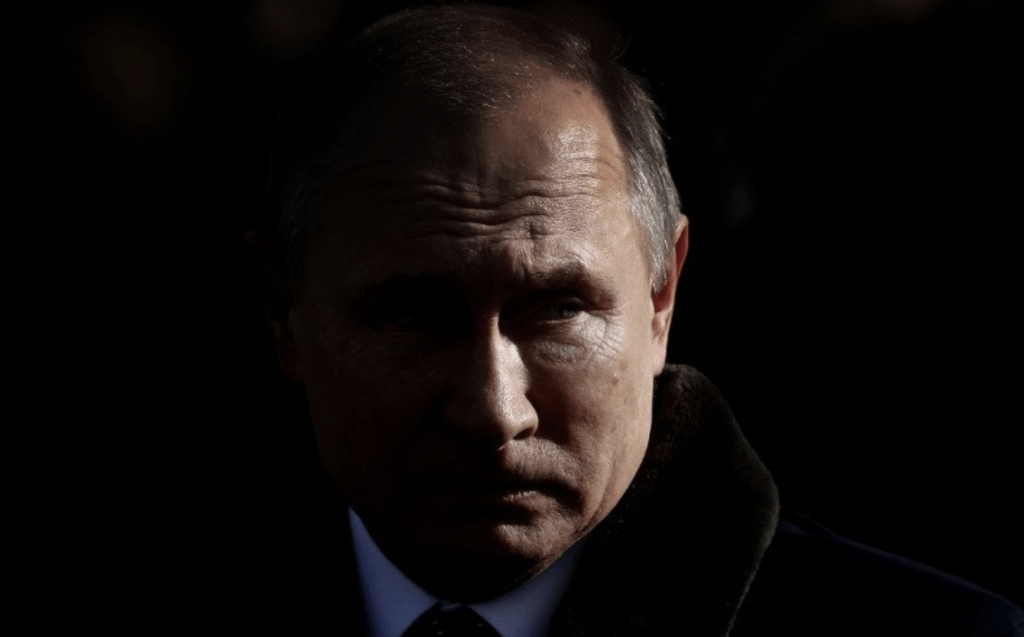

From Russia with Terror: Vladimir Putin, Dystopian Honeytrap

OSW

OSW

Lisa Van Dusen

March 6, 2022.

In the culture of intelligence operations, a honeytrap is a stratagem designed to lure a target into a compromising or incriminating narrative that appears self-sabotaging but is in fact unscrupulously engineered from beginning to end to secure a preordained outcome.

Our popular notion of a honeytrap comes from the old-school, fictionalized version that James Bond specialized in first disarming, then shagging — the double agent assembled from profiling-customized parts to be irresistible, wielding a spiked martini or an ingeniously concealed stiletto.

As an element of the 21st-century narrative warfare currently being waged to undermine democracy — from repugnant performative presidencies to Cecil B. DeMille-scale disruption sieges — a honeytrap can be anything from an offer too good to refuse to a catastrophe too horrible to ignore.

Vladimir Putin’s unprovoked, criminal war against the democracy of Ukraine also serves as a new world order proxy provocation against NATO, Europe, the West and — as the democracy degradation target of greatest strategic value — the United States. That war has already been unprecedented in its deployment of propaganda — including a firehose of falsehood that started in the “pick a casus belli, any casus belli” phase.

This is definitely not From Russia with Love and Vladimir Putin is no Tatiana Romanova. But he is a player steeped in KGB spycraft — a quality that cast him as yesterday’s man for about five minutes in 1999 before placing him ahead of his time as an anti-democracy asset for a new century.

And this is not, if you can stomach a ludicrous oxymoron, a civilized war. It is as much a war on the conventional rules of war, also known as international humanitarian law (IHL) — of which the Geneva Conventions form the core — as it is a war on innocent Ukrainians. Putin did not target the site commemorating the Second World War shooting massacre of 34,000 Jewish Ukrainians at Babyn Yar for territorial gain. He did not stage a cinematic blaze at a nuclear reactor to secure an energy source. Both those propaganda operations carry disproportionate emotional and psychological cargo in a country that lost four million people, including one million Jews, to the Nazis, and that still bears the scars from Chernobyl, the worst nuclear accident in history.

Such blatant psychological warfare, or psyops, has figured in conflict since long before Sun Tzu catalogued its uses more than 2,500 years ago. (If you think Vladimir Putin hasn’t read The Art of War, by the way, consider the images of Russian blundering from the first week of this invasion and the mystery of that “stalled” convoy outside Kyiv in light of this pro tip: “All warfare is based on deception. Hence, when we are able to attack, we must seem unable; when using our forces, we must appear inactive.”) But in our globally connected, collectively assailable, instant-consumption propaganda environment, psychological warfare has gone — forgive the awkward callback — nuclear.

This is definitely not From Russia with Love and Vladimir Putin is no Tatiana Romanova. But he is a player steeped in KGB spycraft — a quality that cast him as yesterday’s man for about five minutes in 1999 before placing him ahead of his time as an anti-democracy asset for a new century.

And in the larger context of a global war on democracy that constantly pollutes this borderless battlefield with escalations of Wag the Dog, outcome-rationalizing narrative wankery into Wag-the-Hellhound dystopian assaults on the rules-based international order, what happens in Ukraine is definitely not meant to stay in Ukraine. Putin’s most reprehensible acts of terror against Ukrainians are also acts of terror against human beings everywhere on behalf of a worldview that sees truth and freedom as existential threats and whose contempt for humanity is now being expressed in ways far more brutal than disenfranchisement alone.

Which is why the world has responded so viscerally to the David-and-Goliath courage and resilience of the people of Ukraine, including its actor-turned-politician president, Volodymy Zelenskyi, in telling a power-addled Marvel villain to idy nakhuy, per the viral response of Ukraine’s Snake Island soldiers to a Russian warship — now an exuberantly profane hashtag.

The difference between the current humanitarian intervention debate and previous ones is that this one unfolds within a larger operational war that includes the weaponization of treason, the commodification of mendacity, the covert use of strange-bedfellow proxies, operational propaganda posing as journalism, and a reliance on tactical intractability and strategic corruption to secure otherwise unthinkable results. Those are the unseen advantages in this dynamic that give Putin what appears to be an irrational level of confidence, interspersed with what may or may not be disinformation as to how justified that confidence is.

So, the chances of a NATO intervention plan being besieged or subverted by all of the above — as have so many high-value political and geopolitical narratives of recent years — must be factored in. That perverse calculation was not generated by Western governments. It is the product of an aspiring world order whose shameless embrace of evil as a means to an end of power consolidation has only one near-precedent, in scope and scale, in modern history.

Which is not to presuppose what should or should not be done to help people who, based mostly on location and timing, have become human pawns in a larger war. But to quote Sun Tzu, “If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles.”

Lisa Van Dusen is associate editor of Policy Magazine. She was Washington columnist for the Ottawa Citizen and Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News, and an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington.