From My Parents’ Homeland to My Own

As a journalist and then a polling executive at the Angus Reid Institute, Shachi Kurl has explored the questions around immigration and its role in the Canadian experience and identity. As the Canadian-born daughter of immigrants herself, Kurl understands how emotional the issue can be. And, especially during an election year at a time when immigration has become a loaded issue across Western democracies, just how politicized it can get.

Shachi Kurl

Allergies. Specifically, a violent allergy to ragweed.

We’ve come to expect the origin stories of Canadian immigrants to be more romantic, or dramatic. Flight from conflict. First steps into a new culture. Canada as a deliberate destination, a conscious choice.

For my parents, it was an accidental affection. By the time they drove up to the Peace Arch border crossing between Washington state and British Columbia, they had already lived in the United Kingdom and the United States, having emigrated from India.

But the American dream was not to be for my father. His teaching options limited him to universities in the Midwest, which limited him to terrible health due to hay fever. So, he and my mother packed up their lives, (including their most precious possession, my sister) and set off for Vancouver.

The beauty of the Coast Mountains was a strong selling point, the salty crispness of fresh marine air wafting from the Pacific Ocean sealed the deal.

My story of Canada is one of a choice made for me. I was among the first generations of Canadian-born children of immigrants educated under official multiculturalism. When you’re little, you’re not alive to the importance of it. You just know that you’re in a school full of kids whose parents—or who they themselves—were born in other parts of the world. We ate different foods. On special occasions, we wore different clothes.

They brought the RCMP in to pose with us. It made for a sweet tableau, but having kids in a school mostly populated by the children of immigrants put on “ethnic dress” and smile with a police officer wasn’t just bromide, it was crucial to trying to build trust in a law enforcement institution that often suffers from a lack of it, particularly among visible minorities. Other facets of multiculturalism policy led to classroom discussions and events that exposed us to cultures beyond those of the so-called founding nations, French and English.

Just as Francophones took a sense of meaning, belonging and long-sought equality from official bilingualism, multiculturalism policy has helped solidify a sense of place in the centre of society, not on the margins, for visible minorities. It provided a sense of parity.

By design, the decades have revealed Canada to be successful in the way newcomers settle in this country. Employment rates among people born outside Canada are higher than many other Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) nations. Due to the points system, two-thirds of Canada’s foreign-born adults have completed post-secondary education, notably higher than the rate for Canadian-born adults and significantly higher than the foreign-born rate for all other OECD countries.

These outcomes beget financial success. In Vancouver, the country’s most expensive housing market, the average assessment value of single detached homes owned by immigrants is nearly 20 per cent higher than the average assessment of single-detached homes owned by Canadian-born residents. In broad terms, most immigrants to this country are educated, working, and doing well financially.

And yet, for the first time in more than two decades, public opinion polling shows Canadians would prefer to see fewer, not more immigrants come to Canada. This feeling has spiked dramatically in recent years:

So, what’s happening? To start, not everyone may be comfortable with what is literally the “changing face” of our nation. Consider that 2016 census data shows us the number of visible minorities in this country now roughly equal to the number of people in Quebec. By 2036, Statistics Canada projects immigrants will make up more than one-third of the total population. Perhaps it is not wholly surprising then, that two-thirds in this country when polled said newcomers need to do more to “fit in”.

Still, conversations of assimilation and integration have been the perpetual undercurrent flowing parallel to the debate over immigration, even during times of support for acceptance of more newcomers. So, it can’t explain everything. Instead, I would suggest two key occurrences that straddled the Trudeau government’s mandate, and the political reactions to them, are more likely responsible for this unenthusiastic response to more immigration.

The first was the resettlement of Syrian refugees, the second, the arrival of thousands of people claiming asylum at undesignated border crossings.

Chart 1: Should Immigration Levels Increase or Decrease. 1975–2018

In the fall of 2015, public opinion was overwhelmingly of the view that this country had a role to play in mitigating the human tragedy unfolding in the mass migrations from the Middle East and North Africa. But until the drowned body of Alan Kurdi—the three-year-old boy whose aunt was so desperately trying to get him and his family to sanctuary in Canada—washed ashore in Turkey, public opinion was also divided over whether people fleeing Bashar Al-Assad’s brutal regime should be resettled here—and if so—how many? That began an election campaign bidding war that saw each of the main party leaders—Stephen Harper, Justin Trudeau and Thomas Mulcair—up the ante over the number of refugees who would be accepted, and under which timelines.

What we may have forgotten was the new Liberal government’s initial insistence that 25,000 Syrians would be resettled within less than two months. Much concern and criticism over seemingly impossible timelines over security and vetting ensued. At the time, Angus Reid Institute polling showed half of those Canadians who said they were opposed to resettlement pointed specifically to the timelines as the reason why.

In response, then-Liberal Premier Kathleen Wynne’s suggested such concerns “… allows [sic] us to tap into that racist vein when that isn’t who we are.”

Whether the federal government gave into the tapping of a ‘racist vein’, or whether bureaucrats convinced their political masters the timelines were indeed, too tight, the settlement date was extended.

Wynne’s comments would not be the only example of political rhetoric took precedence over an important opportunity to communicate to Canadians about the country’s immigration policies.

For the second time, a politician squandered a critical opportunity to strike a careful balance in response, instead going for the feel-good factor that may ultimately have done more damage to the immigration debate overall. In January 2017, Prime Minister Trudeau tweeted, “To those fleeing persecution, terror & war, Canadians will welcome you, regardless of your faith. Diversity is our strength #WelcomeToCanada”

But what came to national attention as something of a curiosity—and for many a representation of the “best of Canada”—later gave way to pointed questions about how officials planned to deal with the tens of thousands who would later arrive, seeking to make a home on this side of the 49th parallel.

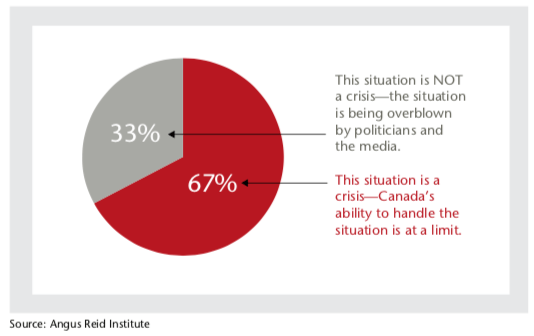

By September of 2017, slightly more than half of Canadians said the country has been “too generous” to the border crossers, more than eight times as many as those who said Canada hasn’t been “generous enough”. By August 2018, following another summer of asylum-seeking arrivals, two-thirds were calling the situation a “crisis”, and the country was having to grapple with uncomfortable questions about how welcoming we really are.

Wynne’s comments would not be the only example of political rhetoric took precedence over an important opportunity to communicate to Canadians about the country’s immigration policies.

What has been the impact of these two narratives on our views towards immigration overall? Consider the potential damage that has been wrought by ideological reactions that failed, at least initially, to acknowledge or straightforwardly address the expressed anxieties of Canadians. I would posit that it has also had the effect of obscuring important differences over the kind of immigrants we mostly accept.

In 2018, the refugee and humanitarian class accounted for just 15 per cent of the number of permanent residents accepted into Canada— and did not include those who had crossed the border irregularly. Family class immigrants, those sponsored by a relative who is already in the country as a permanent resident or citizen, account for 28 per cent of the total.

The rest (57 per cent) are economic class immigrants, those who come fill jobs. You probably wouldn’t know this based on the conversations about immigration today. And yet, we need work-ready newcomers to hold up our tax base, to fill labour shortages. To pay for the nice things we like to have in this country, such as health care and pensions and transit. We’re neither having enough babies nor building enough robots to do that without our immigrants.

Can we absorb more newcomers of all classes into our nation? Arguably yes. Do our leaders need to make a stronger case for them? Very much so.

Chart 2: Canadian Views on Irregular Border Crossings

We can no more take for granted a perpetual approval in public opinion of more immigrants any more than I can take for granted the gift my parents bestowed upon me to make this my home. I recognize this gift when I board flights home to Vancouver and give thanks that I am a woman living in Canada, free from much of the societal, cultural and official repression, harassment and barriers to economic upward mobility faced by so many of my sex around the world. I feel it when we raise the flag on July 1 and marvel at the relative ease with which we live; no war, little corruption, a civil society that functions the way its supposed to.

We have a gift to bestow upon those who don’t have these things. We also have a responsibility to ensure our quality of life is maintained by ensuring our workforce remains robust and skilled. Immigration is the key to both. We need to be more rationally, more frequently, and more emphatically reminded of this.

Shachi Kurl is Executive Director of the Angus Reid Foundation, a national not-for-profit polling and public opinion research firm based in Vancouver. A former journalist, she writes a column in the Ottawa Citizen and is a frequent guest on broadcast panels such as At Issue on CBC’s The National.