Free at Last*: Make Emancipation Day a National Holiday

The declaration of August 1st as a national Emancipation Day holiday would be an obvious way to acknowledge ongoing systemic racism within a continuum of injustice.

Editor’s note: On March 24, 2021, the Canadian House of Commons voted unanimously to recognize August 1st as Emancipation Day across the country.

Tiffany Gooch

July 31, 2020

Growing up in Windsor, my Emancipation Day was annually spent connecting with elders and learning of the stands taken and sacrifices made by generations before my own, striving toward human dignity for all.

I remember a particularly sad moment alongside local historians when a commemorative plaque was delayed, again, this time with the excuse of an election. The Amherstburg Regular Missionary Baptist Association, comprised of ten churches, stood over 150 years as a historically Black Canadian institution, with South-Western Ontario church buildings that were used as a part of the Underground Railroad. The devastation in that room as we learned it could be another year before a plaque would be unveiled and celebrated was crushing. It was ridiculous to me, as a child, that elected officials would delay the long-awaited historic building acknowledgement in a dismissive letter.

This year, I had high hopes for Emancipation Day. At the midway mark of the UN International Decade for People of African Descent, federal leaders were having more pointed discussions about the failures in our systems. The declaration of August 1st as a national Emancipation Day holiday, accompanied by an apology, would be an obvious way to acknowledge ongoing systemic racism within a continuum of injustice. Black history societies across Canada, and especially the Ontario Black History Society, have been leading efforts to see this holiday declared for decades.

Emancipation Day in Canada marks the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, which came into effect in Upper Canada on August 1st, 1834. Proclaimed a holiday in Ontario in 2008, it is a day to celebrate freedom fighters, and commemorate the slow and incremental strides made toward democracy in Canada for all. It is a day to remember that we were once governed by leaders whose families owned other families and their descendants, and that our political systems sought to compromise and grandfather-in liberty so as to protect their economic interests. And so this is a day to acknowledge that freedom was not given, but hard fought-for and won.

It is through this lens that we can understand how institutional structures were not built for Black people in Canada to succeed, and how overcorrection is still required all these years later as the legacy of that structural inequality remains prevalent today.

That legacy is apparent in everything from the casual racism that registers in myriad transactions and fleeting, impactful choices to the refusal on the part of some public figures to even acknowledge systemic racism based on the word of the people who actually experience it.

Canada has been a meeting place of African diaspora groups over centuries, including those who were gradually freed by the Slavery Abolition Act, those who sought freedom and refuge here following the Slavery Abolition Act, and generations of immigrant communities from Africa and the Caribbean, each making meaningful cultural contributions to this country.

We can and must take an honest look at the lived experiences of Black people living in Canada today and see policy gaps closed where they continue to persist.

While the COVID-19 pandemic ultimately put a halt on national festivals this year, international marches erupted as a global movement galvanized around the murder of George Floyd.

With this seismic shift, institutional leaders have begun using the appropriate language and acknowledging their roles in perpetuating anti-Black racism within our systems and communities. Beyond those statements, we need leadership with visionary approaches to responding to this global movement demanding change.

The commitment to “recognition, development, and justice” as laid out in the framework of the International Decade for People of African Descent seems to have been stunted at “recognition” in Canada. Without foundational development support, justice will elude us.

The disproportionately negative outcomes Black people living in Canada experience through our justice, health care, education, children’s aid, and economic systems make it clear that there is more work to be done.

That legacy is apparent in everything from the casual racism that registers in myriad transactions and fleeting, impactful choices to the refusal on the part of some public figures to even acknowledge systemic racism based on the word of the people who actually experience it.

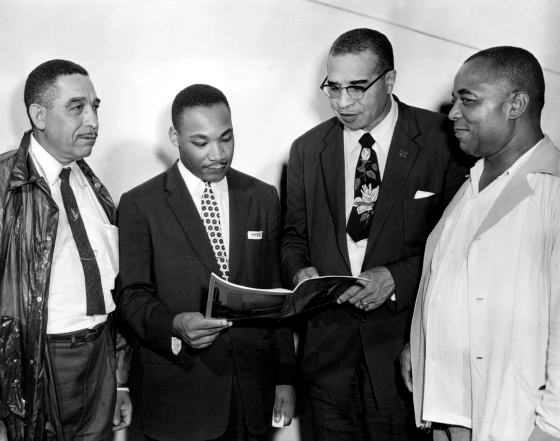

A critical mass of responsive and understanding government leaders is needed at all levels of democratic forums in this country. We can combat institutional anti-Black racism in Canada with leaders inspired by the late US Congressman John Lewis, by bringing good trouble to our democratic institutions until everyone is respected and lifted.

In his posthumously published New York Times essay, Representative Lewis laid out the path forward:

“You must also study and learn the lessons of history because humanity has been involved in this soul-wrenching, existential struggle for a very long time. People on every continent have stood in your shoes, through decades and centuries before you. The truth does not change, and that is why the answers worked out long ago can help you find solutions to the challenges of our time. Continue to build union between movements stretching across the globe because we must put away our willingness to profit from the exploitation of others.”

All across Canada, there are Black women and men performing miracles with very little to preserve Black Canadian history, provide research for current impacts or advocate on a case-by-case basis to see commemoration and sustainable programs created to correct longstanding inequities. As important as it is to acknowledge how far we’ve come, we must not mistake recognition for justice.

It has been a tragic year, and an especially difficult one to not be able to come together across generations. My heart breaks with each community pillar that has fallen during this COVID-19 crisis.

But we will meet, safely, again.

In the meantime, I will dream of Emancipation Day in 2024. I hope to see mammoth national celebrations bridging the final year of the UN International Decade for People of African Descent and our renewed commitment to freedom. I look forward to moments of connection with Black Canadian leaders while gathered around beautiful new monuments across the country; shared stories of groundbreaking change made and cookouts of epic proportions in Jackson Park in Windsor, historic freedom celebrations in Owen Sound, and the world-renowned Caribana festival in Toronto.

The African diasporic waves that have shaped Canadian culture are deserving of seeing their contributions set in stone. The reinforcing silver lining of 2020 is the collective consciousness coming to a new understanding of the Black experience in Canada and imagining a better way.

What does freedom look like beyond 2020? A world where the honesty, self-examination and moral inventory with which we processed all of these events — the ugly persistence of racism, the murder of George Floyd, and the immortal legacy of John Lewis — have translated awakening into the kind of serious change that is needed. As John Lewis might say, that’s the prize we should have our eyes on.

Tiffany Gooch is a Toronto-based Liberal strategist and writer. Her last piece for Policy was Beyond Blackface: Repairing the History of Anti-Black Racism.