Fixing the Fisc: Free Advice for Canada’s Next Prime Minister

Shutterstock

Shutterstock

By Sahir Khan

March 13, 2025

For as long as Mark Carney is Canada’s new prime minister, and beyond that into the outcome of the upcoming federal election, the country’s political leader will get lots of advice on policy and political options. This is not that kind of note. This isn’t about what government puts in the window to win support, or to avoid sticker shock among voters. This is about the fiscal plumbing of government…unsexy but necessary to get right.

Fiscal plumbing is about the decisions governments take on how to allocate and spend public money, the controls in place to ensure spending delivers results, and the people interpreting the rules. Like regular plumbing, it is often unseen, but when mistakes are made, the repercussions can be unpleasant and damaging. It is crucial that these often unseen and undiscussed systems work to foster sustainability, transparency, and deliver results.

Hereby some free advice on fixing our fiscal plumbing:

Ensure sustainable public finances

- Establish a meaningful fiscal anchor – stuff that can be measured, that builds constraints into the system, and drives an internal competition for the best, most considered ideas.

- Review spending by department – figure out what aligns to priorities, is effective and efficient…and what isn’t.

- Reallocate funding to what matters most – that means linking resources, programs and outcomes.

- Grow the economy to manage current spending or get ready to cut, and it will hurt

Get the system in order

- There are no easy fixes, i.e., AI, large IT projects, attrition, won’t fix this

- Get the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) to the job it is legislated to do and put it at the front of the process. This is not for English majors (no offence intended), but for experts in costing, due diligence and program analysis. Departmental Chief Financial Officers should drive cabinet submissions, not just sign-off on them.

- The ‘system’ should be tough at the front-end to catch problems early…you don’t gain popularity from being tough, because people expect it; but, when ‘the system’ fails, you get kicked out of office.

Tell people what you’re really doing

- Fix the budget process, i.e., report like the majority of OECD countries (please see below for details)

- Get parliament to do its job. It’s better for everyone.

- Hiding behind a weak system is not an excuse. Fix the system, make better decisions, get better results. When you do that, you’re not afraid of transparency.

Context for change

It seems that with every election we get a new set of ideas on how to fix government. It appears that that the further away we are from government (e.g. tech, capital markets), the easier the fix seems to be and the more confident are proponents that their ideas will be transformative. Maybe someone sees a book in the airport (e.g. Deliverology) and thinks that this is the shortcut to fixing government. Or maybe you’re watching events down south and are thinking…DOGE looks interesting. It’s not. Let’s not fall into these traps.

With the first election for new Liberal Party and Conservative Party leaders, lots of people will whisper ideas into the ears of the leaders and their teams. Some leaders will feel new fiscal pressures and will look for ways to spend while trying to look fiscally responsible.

In this context, it’s important to remember that governments do the stuff that nobody else wants to do. Please think about this for a moment. Canadian Forces personnel are prepared to die to protect our country. First responders go towards the hazards, not away. Public servants design and deliver programs to reduce poverty, improve health outcomes and drive long-term economic growth.

The private sector generally gets involved when they think that there is money to be made in solving public policy problems. As shareholders, we should want this. We want companies to maximize shareholder value. On the other hand, as taxpayers, we want governments to speak for all constituents and put reasonable constraints on these activities to ensure that externalities are contained. Governments must also ensure that the risks and returns for the private sector partners are well understood. This is not often the case (e.g. see P3s and the failure of risk transfer; large IT project run amok; defence procurement delayed or with ballooning budgets).

Public financial management

Getting government right is key to maintaining the confidence of Canadians in their public institutions. To that end, we can use public financial management as a lens for a series of reforms that are achievable over the course of a single mandate and tend to align with good practices in other OECD countries.

There are four objectives of a well-functioning public financial management (PFM) system and government:

- Sustainable public finances (real fiscal anchors that ensure that debt is declining relative to GDP while maintaining competitive tax rates)

- Spending on priorities of Canadians (keeping in mind that Canadians can be fickle and contexts change)

- Effective and efficient spending (delivering for results)

- A transparent budget process (there is no accountability without transparency)

Dr. Alan Schick of Brookings and the University of Maryland developed a version of this framework in 1998: A Contemporary Approach to Public Expenditure Management. Kevin Page and I call him the godfather of budgeting and have been mangling his work for our own purposes for the last 20 years. Alan always thought it was hilarious.

Some fiscal background

Public finance matters but probably not in the way a lot of people would think. There is little correlation between an incumbent government’s fiscal balance and their subsequent electoral result. However, governments lose elections on the failure of execution, particularly the longer they are in power.

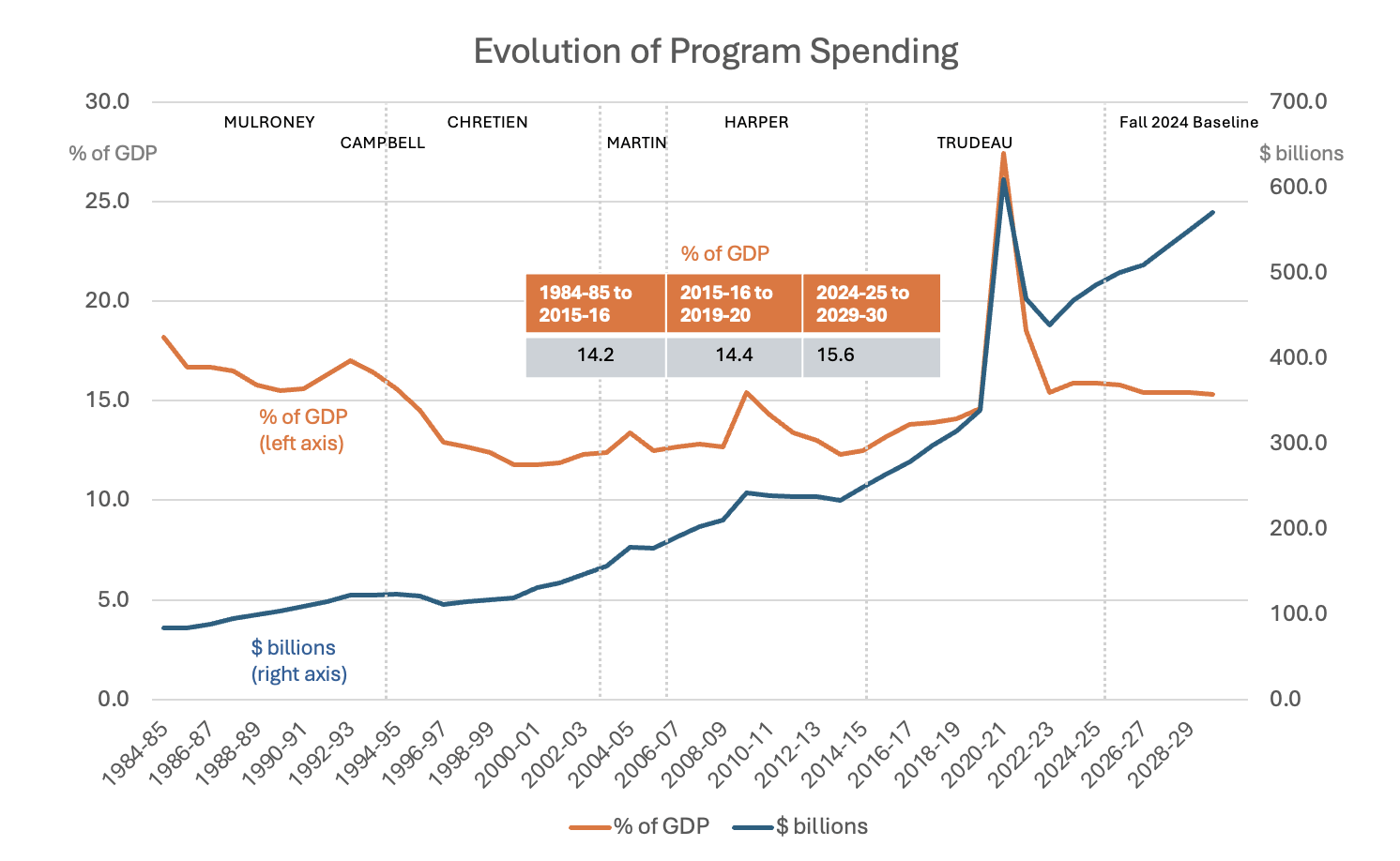

Through the tenures of Jean Chrétien, Paul Martin, and Stephen Harper, federal government spending stayed within a range of 12-13% of GDP, barring a crisis here and there. The Trudeau government has program expenses at about 16% of GDP, breaking what some might argue was a social contract. Further, the emphasis of the new spending was social in nature, rather than economic, with execution being a weak point for the government.

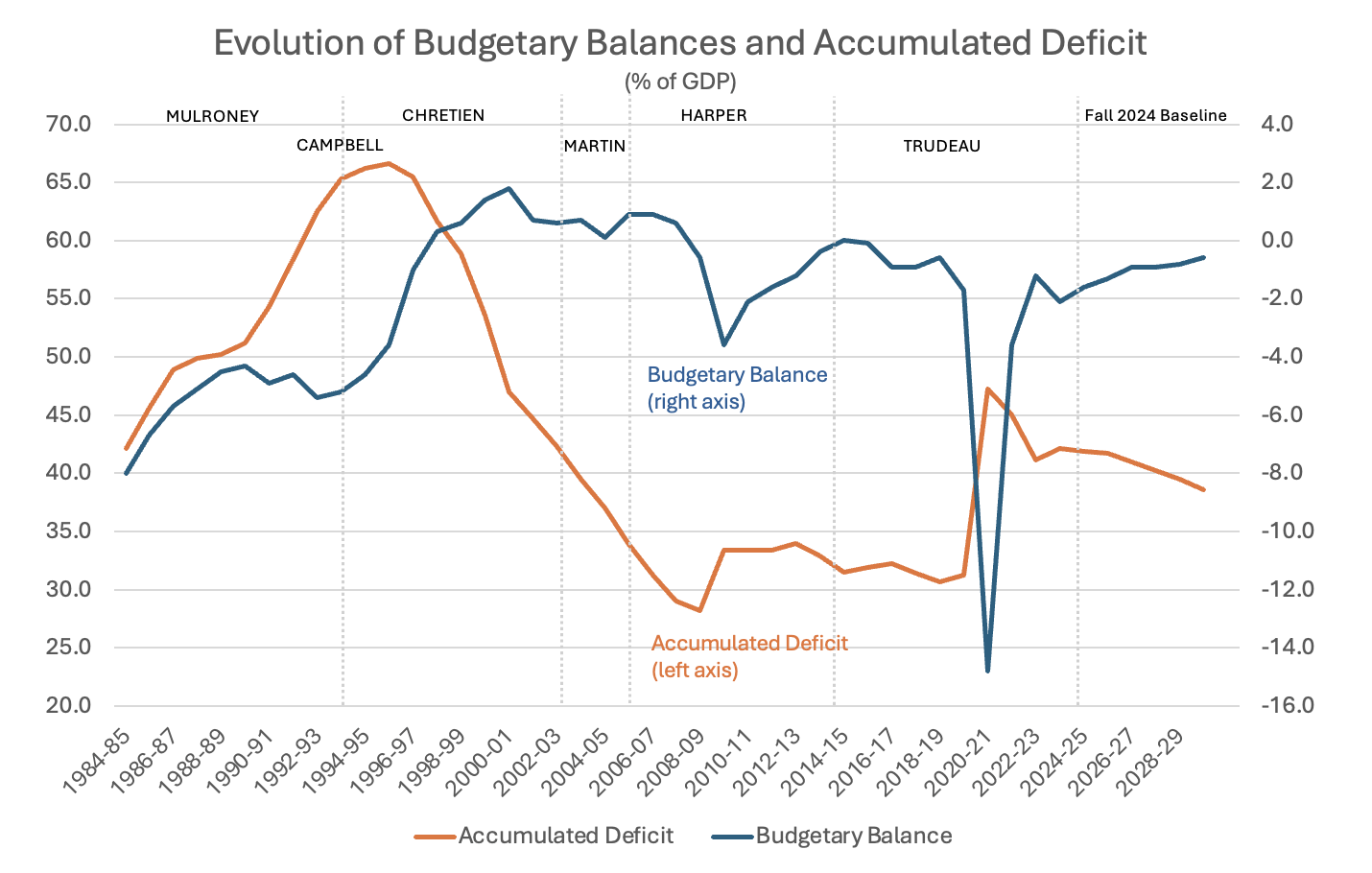

But this requires a little nuance…over the last 10 years, revenues as a percent of GDP have also increased without an increase in the tax rate (except for a new tax bracket). The federal government had a positive primary balance from 2014-15 to 2018-19, when COVID led to a significant primary deficit. The last two years show revenues at 15.7%, a small primary surplus in 2022-23, and a small primary deficit in 2023-24 (mainly due to the booking of the Indigenous settlement-related contingent liabilities). The recent Parliamentary Budget Officer forecast shows a primary surplus for 2024-25 and the next four years.

We also need to keep in mind that one of the reasons budgetary balances don’t appear to loom large in recent elections is that the measures undertaken by Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin in the 1990s gave us a fiscal structure that enabled Canada to withstand COVID and can be expected to weather a trade war with the United States. The challenge is that the fiscal crisis of the 1990s was decades in the making and the result of unsustainable spending…one program, project or transfer at a time.

How to regain public confidence

So, the popular political dialogue is to reduce spending. Depending on your ideology, this might mean keeping the status quo, rebalancing between social spending and economic or reducing spending to levels before the Trudeau government took office. It’s easy to say that we want to go back to the spending levels of the Chrétien government, but the 3 percentage points of spending, relative to GDP, is worth about $90 billion dollars per year.

But a US-Canada trade war, pressure to increase defence spending to reach 2 or 3% of GDP, tax cuts, and new investments mean that to maintain fiscal anchors, the arithmetic will have to work. We are hoping that party platforms for the upcoming election will help fill out these details.

There is also the reality is that the current 16% spending level is hard coded with social programs like dental, pharma, childcare, child benefit and Indigenous reconciliation (40% of the growth in spending). Canadians are attached to the entitlement programs and some of the Indigenous spending was the result of litigation that the federal government lost. The next government will likely have to outgrow this spending, while accommodating for new spending to deal with the US trade war and higher defence spending.

What is also missing from the current system is a meaningful fiscal constraint that forces ongoing priority-setting in the public service. When lots of money is sloshing around the government, the system of internal controls tends to get sloppy, and the culture is based on competition for new announcements and speed. Costing, due diligence and execution considerations tend to take a back seat. This isn’t really about money, it’s about culture. The next government will have to compel the public service to treat every dollar like it matters — poor performers are let go, tech is integrated where practical and you invest in the people you keep.

A comprehensive spending review is required

Avoid gimmicks (e.g. AI, large IT projects, efficiency reforms). Many of these have failed in the past. If you are a leader or a potential minister, please remember to ask people old enough to give you the history. Please keep in mind that program cuts are politically difficult but fiscally reliable (only 16% give-back in the 1990s Program Review). Efficiency savings are politically easy but fiscally dubious (2005 procurement reform written-off, Phoenix payroll, secure channel, Shared Services Canada etc…).

The 2012 Deficit Reduction Action Plan (DRAP) worked by laying off 35,000 public servants. It might have been inelegant, but it got the books largely back to balance; a political objective rather than an economic one, to be sure.

Some parliamentarians and columnists have mused about cuts to the federal public service as the backbone of a fiscal strategy to right-size spending; the “easy button” as it were. This will likely prove disappointing. The current public service payroll is $62 billion. Whether a government aims to 5% or 20% of the workforce, with annual savings of $3 to $12 billion respectively, the larger the cuts, the more significant the impact on services to Canadians. And these savings will be partially offset in the initial year with workforce adjustment costs. Further, pension penalty waivers and enhanced severance might be required to ensure the right mix of departures. Finding the “right size” of government should be part of a human resource strategy that falls out of a government’s policy priorities, fiscal strategy and a determination of the type of capacity needed to effectively and efficiently deliver services to Canadian. Cuts may be part of the agenda, but they shouldn’t drive the agenda.

So, reducing the public service payroll will have only a minor contribution to fiscal consolidation. While cost reductions are important, a rebalancing between social and economic/defence spending, coupled with an emphasis on program performance, is what is required.

A focus on reallocation and program performance should drive a spending review where every department will have to assess each program on three criteria:

- Is it aligned to the priorities of the government (i.e. does the federal government need to do it)?

- Is the program effective (i.e. delivering results)?

- Is the program efficient (i.e. are there more efficient instruments or method of delivery)?

Led by the deputy minister, departments should identify the bottom 10% of spending for potential reallocation or reduction, depending on the priority. An external board should review the efforts of each department. Treasury Board should lead the exercise for central agencies.

With execution and delivery being ongoing challenges, the review should also examine why projects such as ArriveCan and Phoenix failed and what measures can be put in place to prevent such failures in future.

Such an exercise will be challenged by the lack of information on inputs, outputs and outcomes for each program, but rebuilding the information should be the first task of every deputy minister.

The composition of the public service should flow out of the government’s priorities and the program review. The structure and resources should flow from these priorities. If it isn’t necessary, reallocate it. Program Review in the 1990s meant both a leaner public service and a clear role for other partners in the private and not-for-profit sectors.

Commit to including parliament in the process. This can start with large procurements and capital spending. There is rarely a political win for government in large IT, defence or other capital projects. Expanding the accountability will share the credit but also the downside political risk.

Expenditure management, budget making and cabinet

The expenditure management system can only be controlled at the front end of decision-making. In the current process, Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) is largely symbolic in its role. Cabinet scrutinizes some new measures while others go to the budget process directly (e.g. two-pagers). The level of rigour on new spending measures is uneven at best, delinquent at worst.

Have new measures go through Treasury Board before cabinet and before budget consideration. In our current system, the Privy Council Office tends to focus on prioritization. Finance focuses on the economy and aggregate fiscal discipline. Once cabinet has approved a policy and the prime minister (PM) and finance minister (FM) have approved funding notes, to go with the policy committee recommendation, things are largely good-to-go. Later, TBS spends time on costing, instruments, authorities and performance but has a role, in our PFM system, that ends up being largely symbolic. Treasury Board ministers rarely overturn decisions of the PM, FM and Cabinet. In our system, there are few incentives to recognize failure or to attach performance to programs, unless it is positive.

We need to turn the system upside down…start with the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS).

When considering new spending questions, ministers and central agency officials may wish to ask the following (you don’t even need to read the submission to ask):

- Can you clearly identify the problem that you are solving?

- Has any other jurisdiction faced this problem? How did they address it (i.e. real options analysis)?

- Do you understand the current and future states? (Status of a process or organization before and after changes are made)

- Do you have a plan to realize benefits and manage risks and the experienced team to implement it?

- Do you know how much the measure will cost?

- Do you have a performance measurement framework to capture inputs, outputs and outcomes (and to report transparently)?

TBS is the place to figure out the issues around costing, execution and results. Once we have properly kicked the tires at TBS, then a new measure is ready for cabinet consideration. This also means empowering chief financial officers in line departments to take a leadership role in cabinet submissions, not just signing off on them 24 hours before the meeting. This will slow things down, but they will be in much better shape. This is how Ontario does things and TBS is taken far more seriously than at the federal level. Like the chess mantra from the movie Searching for Bobby Fischer, cabinet should live by the creed: “Don’t move until you see it”.

A few things to remember for the next prime minister…if you are told that the Canadian context for a new measure is unique and requires a one-off custom solution, then strap-in for another boondoggle, whether it’s a new program or IT project or defence procurement. We need to buy at marginal cost even if that means solving only 80% of the problem (as identified by peer jurisdictions). The cost of the last 20% will be astronomical.

Stop making the budget about incremental spending

Let’s stop being the exception of the OECD in how we budget.

Let’s normalize timelines on the federal financial cycle. We can set fixed dates for the budget, mid-year update and public accounts. These don’t need to be politicized. The public service will adapt. Political leaders will still get their announceables.

Integrate the budget with appropriations and do so with a single accounting language (i.e. accrual). Present the budget in its totality, like other OECD countries, instead of only presenting new measures. Include a renewed Annual Reference Level Update (ARLU) process, for previous spending decisions already in the fiscal framework, to ensure that all spending is considered alongside new measures. Include tax expenditures as part of the annual budget exercise. This is about $150 billion in annual expenditure that does not go through parliamentary scrutiny.

Present the budget and main estimates together as a single document. Supplementary estimates bills can deal with off-cycle measures.

You shouldn’t need a decoder ring to understand the budget, estimates and public accounts, with different accounting languages. Implement a citizen budget to promote transparency and public participation. The International Budget Partnership calls this best practices. It will democratize budgeting.

Better spending, better transparency, better results

For a new government, setting the tone early is critical and that is done by setting a few, clear, measurable priorities and having other people measure them (you can’t mark your own homework). Clear fiscal anchors can be measured by the PBO. Tangible results on the NATO target can be tracked by NATO itself. Economic and productivity growth measured by StatCan. Put this all on a website dashboard. Cut the comms spin, focus on the serious work of getting sh*t done.

While strengthening the Parliamentary Budget Office to assess the prospects of the government’s fiscal targets, the PM may also wish to adjust the tenure of the PBO to a single term, even a longer one, to avoid making the renewal a political issue. This is the practice with the Auditor General (AG).

Including Parliament in the federal financial cycle can’t just be some pre-budget consultations at the finance committee and some video clips from public accounts after an AG report. Launch an advisory panel to drive reform of the estimates and departmental planning process. The advisory panel should work with both the government and the government operations (OGGO) committee of parliament. Ultimately, we want parliamentarians to vote on program activities rather than operating, capital, transfers.

Make better use of standing committees and the PBO in reviewing spending and eliminate the deemed rule; parliament’s power of the purse should no longer be taken for granted. Link the departmental planning and performance reports into how the government actually manages resources and programs and integrate them into the parliamentary financial cycle. Empty reporting is a burden on departments and only provides a synthetic transparency for parliament.

Reform defence procurement by implementing the proposed Defence Procurement Canada agency. When weighing Canadian Forces requirements, fiscal constraints, and Canadian jobs; pick two. Doing all three is very expensive. Recognize that the problems we have in Canada stems in part from small production runs, trying to satisfy too many requirements, not buying from production lines.

Strengthen infrastructure planning with a comprehensive needs assessment and planning approach. Consider the United Kingdom’s models to support analysis and discourse. Focus on infrastructure that drives economic growth, shortens economic distances and ensures a more resilient Canada. Canada can no longer be dependent on other jurisdictions for the platform under its key industries.

Resources are not infinite, and institutions are not permanent; nor is the patience of Canadians with their governments. Change must be practical and results demonstrable within a reasonable period of time. Doing better isn’t just an option but a requirement for the next prime minister. These ideas are designed to be implemented within a single mandate, do not require other jurisdictions to coordinate, and do not require the hiring of additional staff. We hope that some of them will make it into the platforms of Canada’s federal parties.

Sahir Khan is Executive Vice President, Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa and former Asst. Parliamentary Budget Officer. With help from IFSD colleagues Kevin Page, Dr. Mostafa Askari, Azfar Ali Khan and Dr. Helaina Gaspard.