Fiscal Policy and the Post-COVID Recovery

Governments around the world, including Canada’s, have spent nearly a year re-orienting their fiscal calculations around the health and economic Catch-22 of a deadly pandemic that could only be contained by a self-induced economic coma. As COVID-19 vaccines begin to make their way into the bloodstreams of Canadians, the economic recovery could still take many shapes, writes former Parliamentary Budget Officer and Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy founder Kevin Page.

Kevin Page

Historians debate key turning points in history—Pax Romana; the birth of spiritual leaders like Jesus and Mohammed; the invention of the printing press; the renaissance; and many more. Will the 2020 global pandemic mark an inflection point, the beginning of a special moment in human history? Can global leaders imagine a new future? Can countries, public and private sectors and citizens work together to address challenges and opportunities?

The year 2020 started with the spread of the COVID-19 virus around the world. It has ended with the roll-out of vaccines. The pandemic has taken its toll on human lives—1.6 million deaths globally; 13,000 deaths in Canada. In the Dave Matthew’s song “Space Between”, the singer/songwriter makes the case that life is about bridging the gaps that lie between people. The cooperation of international pharmaceutical efforts has highlighted the power of collaboration bridging gaps. Policymakers are now coalescing on agendas focused on sustainability, inclusion and resilience.

Fiscal policy is the use of government spending and revenues to promote growth and the provision of common goods. Economic channels include the allocation of resources, income distribution, savings and investment and aggregate demand. Fiscal policy can be used to stabilize an unstable economy through built-in stabilizers (e.g., unemployment benefits; progressive tax systems) and stimulus measures (i.e., deficit financed measures to strengthen demand). Fiscal policy was an important stabilizing influence in the 2008-09 global financial crisis.

Fiscal policy is the use of government spending and revenues to promote growth and the provision of common goods. Economic channels include the allocation of resources, income distribution, savings and investment and aggregate demand. Fiscal policy can be used to stabilize an unstable economy through built-in stabilizers (e.g., unemployment benefits; progressive tax systems) and stimulus measures (i.e., deficit financed measures to strengthen demand). Fiscal policy was an important stabilizing influence in the 2008-09 global financial crisis.

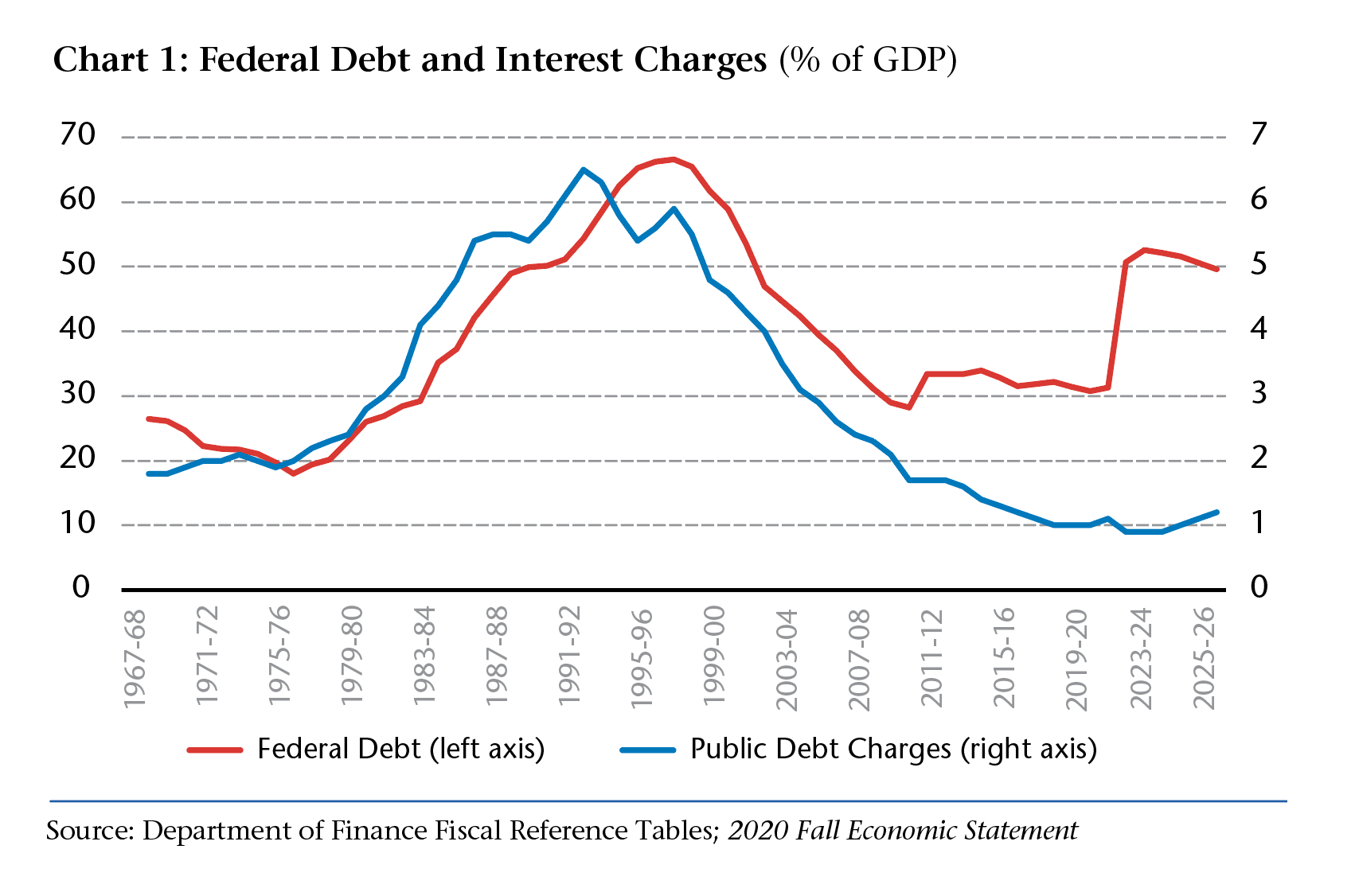

Government capacity to use fiscal policy as an economic stabilizer depends on its fiscal room. The reduction in federal debt in Canada from 66 percent of GDP in 1995-96 to 28 percent of GDP in 2007-08 (corresponding reduction in public debt charges from 5.9 to 1.7 percent) gave the federal government of Canada much needed fiscal space to support the Canadian economy in both the 2008-9 financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic. The fiscal advantage was supported by a AAA bond rating (i.e., highest investment grade) from the major agencies.

Canada unloaded fiscal firepower to support Canadian households and businesses to facilitate social distancing and slow the spread of the virus. Direct fiscal supports in 2020-21 are estimated at $275 billion (12.5 percent of GDP). Total federal-provincial-territorial multi-year supports including tax payment deferrals and credit supports are estimated near $600 billion.

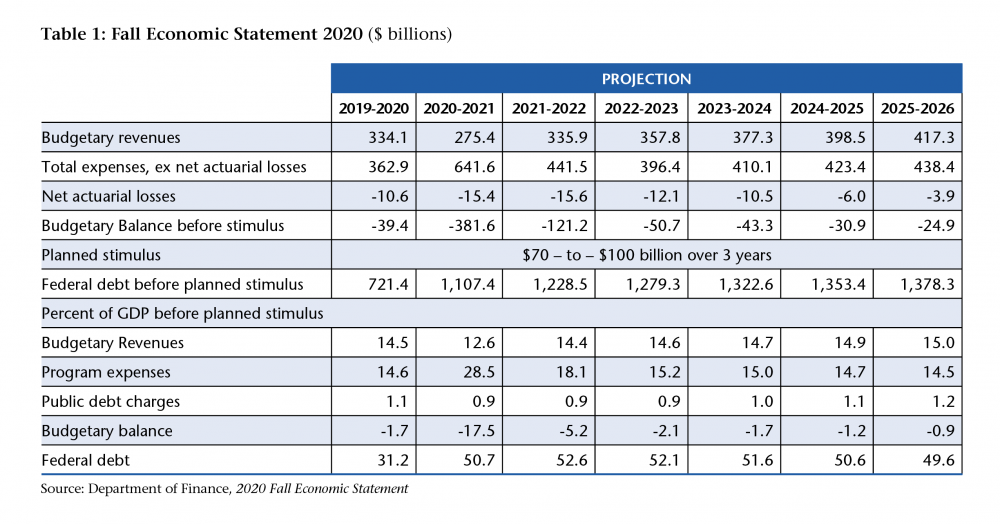

How does the federal budgetary deficit go from $39.4 billion (1.7 percent of GDP) in 2019-20 to $381.6 billion in 2020-21 (17.5 percent of GDP)? Start with $381.6 billion. Take away $275 billion in direct fiscal supports. Take away a $76 billion drop in budgetary revenue from the Budget 2019 projection because of a deep recession. We are left with a deficit of $31 billion—a number that would not raise eyebrows in financial markets in normal times.

Olivier Blanchard, a former Chief Economist at the International Monetary Fund, makes the case that fiscal policy during the COVID19 crisis has three objectives: infection fighting; disaster relief; and support for aggregate demand.

How much fiscal stimulus will be needed to support demand in a post-pandemic economy is an open question. Canadian national accounts numbers for the first three quarters of 2020 show a deep dive, a strong bounce and an increase in savings. Blanchard’s advice is for governments to be ready but should not commit to a specific level of fiscal expansion before the outlook becomes clearer.

There are downside and upside economic risks around the post-pandemic economic recovery. The key driver remains the evolution of the virus. A U-shaped recovery for GDP is linked to struggles controlling the virus and the cumulative impact of scarring on jobs and investment. A Z-shaped recovery is linked to successful global vaccination and the release of pent up consumer demand highlighted by recent increases in savings and the return of investor confidence.

International research on the potential impacts of fiscal stimulus has increased significantly since the 2008 financial crisis and introduction of record-low interest rates. Many factors are seen to influence the effectiveness of stimulus. These include the economic context, and the timing, size, composition and duration of the fiscal stimulus.

International research on the potential impacts of fiscal stimulus has increased significantly since the 2008 financial crisis and introduction of record-low interest rates. Many factors are seen to influence the effectiveness of stimulus. These include the economic context, and the timing, size, composition and duration of the fiscal stimulus.

In the 2020 Fall Economic Statement, the government indicated an intention to use fiscal stimulus to strengthen the post COVID-19 recovery. Different economic scenarios were presented with stimulus values ranging in the $70 billion to $100 billion range over a three-year period starting in 2021. As well, the government indicated intention to use labour market indicators—employment rate, unemployment, hours worked—as guardrails to guide the shape of fiscal stimulus.

One of my favourite holiday movies is “Planes, Trains and Automobiles”’. In the 1987 film, the principal characters, including Jim Neal (played by Steve Martin) and Del Griffith (played by the late Canadian icon John Candy), struggle to get home for the holidays. By comparison, our new Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland and newly named Deputy Minister Michael Sabia will spend the holidays trying to get Canada back to fiscal normalcy. The Finance movie would be more akin to “Fiscal Anchors, Guardrails and Rules”.

There is a genuine intellectual debate around fiscal discipline in a post-pandemic environment.

On the one side, some argue that in a low-interest rate environment there is a “‘get of jail free” card for running up large debt to support households and businesses during a lockdown to protect and support growth. Debt-to-GDP should fall with primary budget balances and interest rates lower than the growth in the economy.

On the other side, some argue that higher debt will eventually be paid by higher taxes. They argue it is voodoo economics to assume interest rates will stay low for long and that public investment will pay for itself. Higher debt will limit fiscal room for future generations and create economic instability risks. Fiscal consolidations are costly—a lesson learned in Canada in the 1990s.

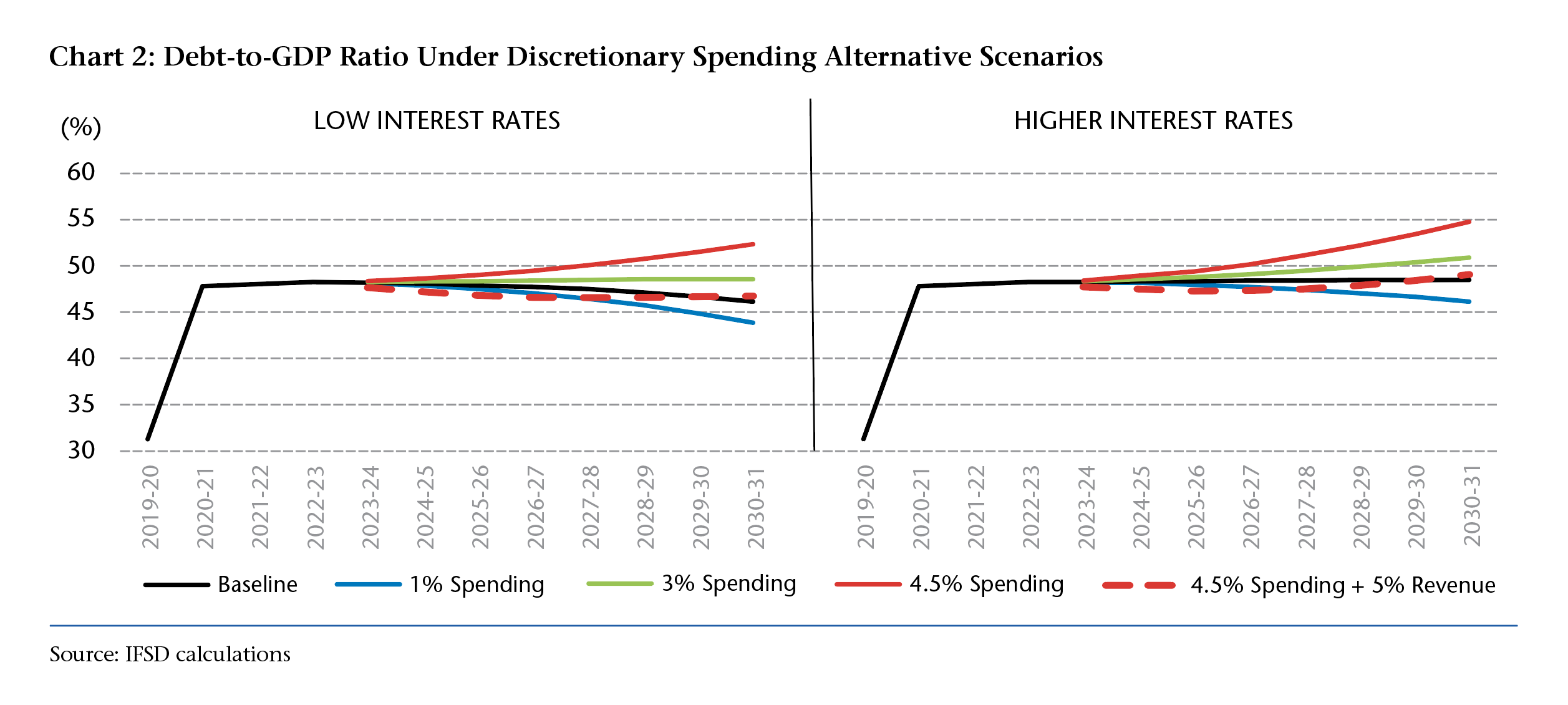

Finance scenarios and work by IFSD suggest Canada is headed for a much higher debt-to-GDP ratio over the medium term—likely in the 50 to 55 percent range. This is well above the 30 percent debt-GDP ratio in the pre-pandemic period. On a positive note, these debt numbers are well below debt loads of most advanced countries. PBO analysis suggests this level of federal debt with the current fiscal structure (i.e., before initiatives highlighted in the 2020 Speech from the Throne) could be sustainable in face of aging demographics. On the other hand, provinces are not sustainable, largely because of assumptions regarding health care spending growth.

It is said that discipline is about knowing what needs to be done, even if you do not want to do it. Canada will need a fiscal planning framework with discipline or risk passing on higher unnecessary debt to future generations; not being able to support Canadians in the next recession; and potentially losing a hard-earned AAA credit rating.

There is lots of good advice on fiscal discipline from international organizations. Are we able to implement it?

- Outline a fiscal strategy. How will fiscal policy be used to support economic recovery and long-term structural policy shifts (e.g. climate change)? How will corrective fiscal measures (e.g. spending restraints and tax increases) be introduced over the medium-term as economic conditions improve.

- Investment spending should be defined. Non-investment initiatives should not be deficit-financed in a post pandemic period.

- If fiscal stimulus is required, a performance framework should be established. Stimulus programming should not have a permanent impact on deficits. Fiscal analysis should accompany the setting of fiscal guardrails (e.g., estimates of the output gap, cyclically-adjusted budget balances, spending and tax multipliers)

- Long fiscal sustainability analysis should be tabled with the budget.

- Set a fiscal anchor. It should be a prudent level of debt relative to income.

- Set fiscal rules. These are operational targets consistent with the fiscal anchor including primary balances (program spending, less revenues); discretionary spending growth; and public debt interest charges as a percent of GDP.

- Establish escape clauses. Fiscal policy needs to adjust if assumptions are substantially altered.

- Use the Parliamentary Budget Office to provide support for Parliament on the enforceability of the fiscal anchors, guardrails and rules.

Contributing Writer Kevin Page is the founding President and CEO of the Institute for Fiscal Studies and Democracy at University of Ottawa and was previously Canada’s first Parliamentary Budget Officer.