Finally, Hope for the Syrian People

Syrians welcoming Bashar al-Assad’s departure in Madrid/EPA

Syrians welcoming Bashar al-Assad’s departure in Madrid/EPA

December 8, 2024

At last, an event the world’s humanists might celebrate.

Finally, one of the world’s entrenched authoritarians has been defeated by a suppressed people. In 2011, when Bashar al-Assad crushed the peaceful democratic protests inspired by the Arab Spring, he did so ruthlessly, with extreme force. Dictators across the world, the military junta in Myanmar, Lukashenko in Belarus, the Chinese state in Hong Kong, Putin in Moscow, many others, took the lesson – crush the protestors without mercy and their cause will collapse.

The demise of the Assad regime after more than a half-century doesn’t prove that the arc of history necessarily bends toward justice – Assad will likely never face true justice – but it may validate the belief that repressed people will find their way.

How did it happen so fast? The Syrian Army was an empty shell, staffed by alienated draftees, and dependent on partnership with Hezbollah, which had just been decapitated and decimated by Israel in Lebanon. Russia tried some more bombing but then read the tea leaves, stretched as they are in Ukraine – Russian warships based in the Syrian port of Tartus have headed for home. And Iran, Bashar’s principal state ally, has other fish to fry, with the US especially.

So, collapse when it happens, happens fast.

Moreover, to whom will the regime fall? The rebels who today occupy the second city, Aleppo, and others on the road to Damascus, Homs, and Hama, are spearheaded by a militant Islamist group, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, not known for democratic impulses. (The US has a $10 million bounty on its leader, a dissident from Al-Qaeda but still hard-line Islamist, al-Julani). The Kurd forces want a separate Kurdish state in the North, anathema to Turkish President Erdogan, who remains in a protracted, bitter conflict with Kurdish separatists.

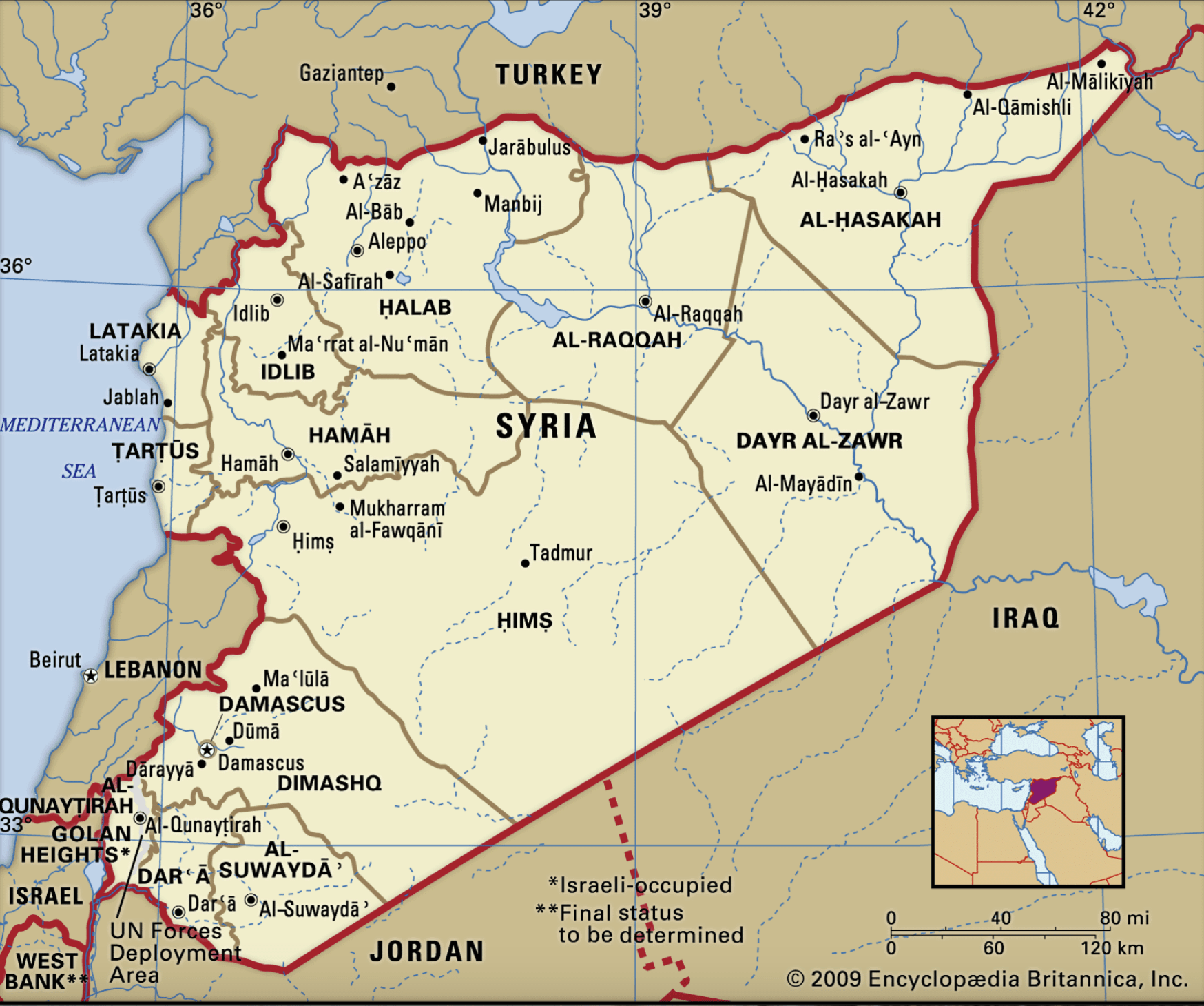

Britannica

Britannica

This morning, Syria’s ruthless dictator is said to have fled to Moscow. He has certainly fled Damascus. He may dream of eventually taking refuge in the relative security of his tribal Alawite heartland on Syria’s Mediterranean coast, in a new Syria partitioned among its diverse inhabitants: Syria’s 2011 population, before the Arab Spring ignited the civil war, was 22 million: about 70% Sunni Arab Muslims, Christians about 10%, Alawites (a more relaxed form of Shia Muslims) also 10%, and almost 2 million Kurds.

Fifty years ago, Hafez al-Assad, Bashar’s father, seized power on behalf of the Ba’ath socialist party, the Syrian version of the Arab nationalist movement, largely secular, that emerged in the 1960s. An Alawite, he extended command and control positions to minority Alawites, who benefited from corruption and favouritism to prosper disproportionately.

He created a police state, crushing all opposition, most demonstrably in Hama in 1982, after terrorist incidents in Damascus, when the army basically destroyed a Shia city that was a centre of protest, killing as many as 20,000 in the process. It became a teachable moment in the dictator’s handbook, known as “Hama Rules” ‑ a term coined by New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman to describe Assad’s brutality. If you protest – cause trouble – this is what to expect.

President Hafez Assad ruled for 29 years, eventually posturing as a benign dictator of a secular country that became almost an ally of the West in the Gulf War to expel Iraq from Kuwait in 1991. But inside Syria, the regime’s corruption and suppression remained resented. When Assad died in 2000, and power passed to his son Bashar, an opthamologist living in London, hope emerged that he would encourage the liberalization of the top-down regime of his father. That didn’t happen.

The fall of Assad will enable some international humanitarian attention to reconstruct the country, but the massive rebuilding needs in Gaza and Ukraine are already extremely daunting.

The Arab Spring was ignited in December 2010 in Tunisia where it chased the local dictator into exile. It spread like wildfire, notably to Egypt, where the massive protests centered on Tahrir Square inspired a popular revolution that brought down President Hosni Mubarak’s corrupt regime. Alas, the democrats could never get a coordinated political program going and became effaced by the well-organized and militant Muslim Brotherhood which formed a government. Its Islamist excesses led to the Army’s intervention and military rule that lasts till this day.

Other democratic movements in the Gulf states failed to dislodge authoritarian monarchs, while in Libya, Gaddafi was pushed out with the help of NATO bombings, but the country descended into the anarchic chaos that persists.

In Syria, however, the Arab Spring’s message of hope, especially to youth, was contagious. After the regime arrested and tortured student protesters, massive peaceful marches took place in Deraa. After the military began to pick off participants with sniper bullets, the protests doubled, brave marchers chanting, “Sniper, sniper, here is my neck, here is my head…”

With US help, a Free Syrian Army was trained, and lawyers and teachers were coached by State Department-funded Americans on how to be effective local mayors and civic officials. US and French ambassadors were attending the funerals of the murdered students. The protests spread.

While the Free Syrian Army, the democrats’ aspirational military fist, never amounted to much, other forces intervened with increasing effectiveness, notably dissident Kurds (trained by the US) from the North, and various Islamist groups, with war experience in Iraq, and, most ominously the Islamic State (ISIS) or Daesh extremists that had already captured thousands of square miles of land, from Iraq to Syria.

By 2015, the Assad regime was considered to be on the ropes. Diplomatic talks debated how the country could be apportioned to the different ethnic/sectarian groups, with the possibility of Assad retreating to the Alawite coastal stronghold. Alternatively, various outside actors speculated that Assad could take refuge in Moscow. The Putin regime was not that committed to saving him, and at that point, it wasn’t a decision Assad could take. Millions of Alawites would lose everything if he defected.

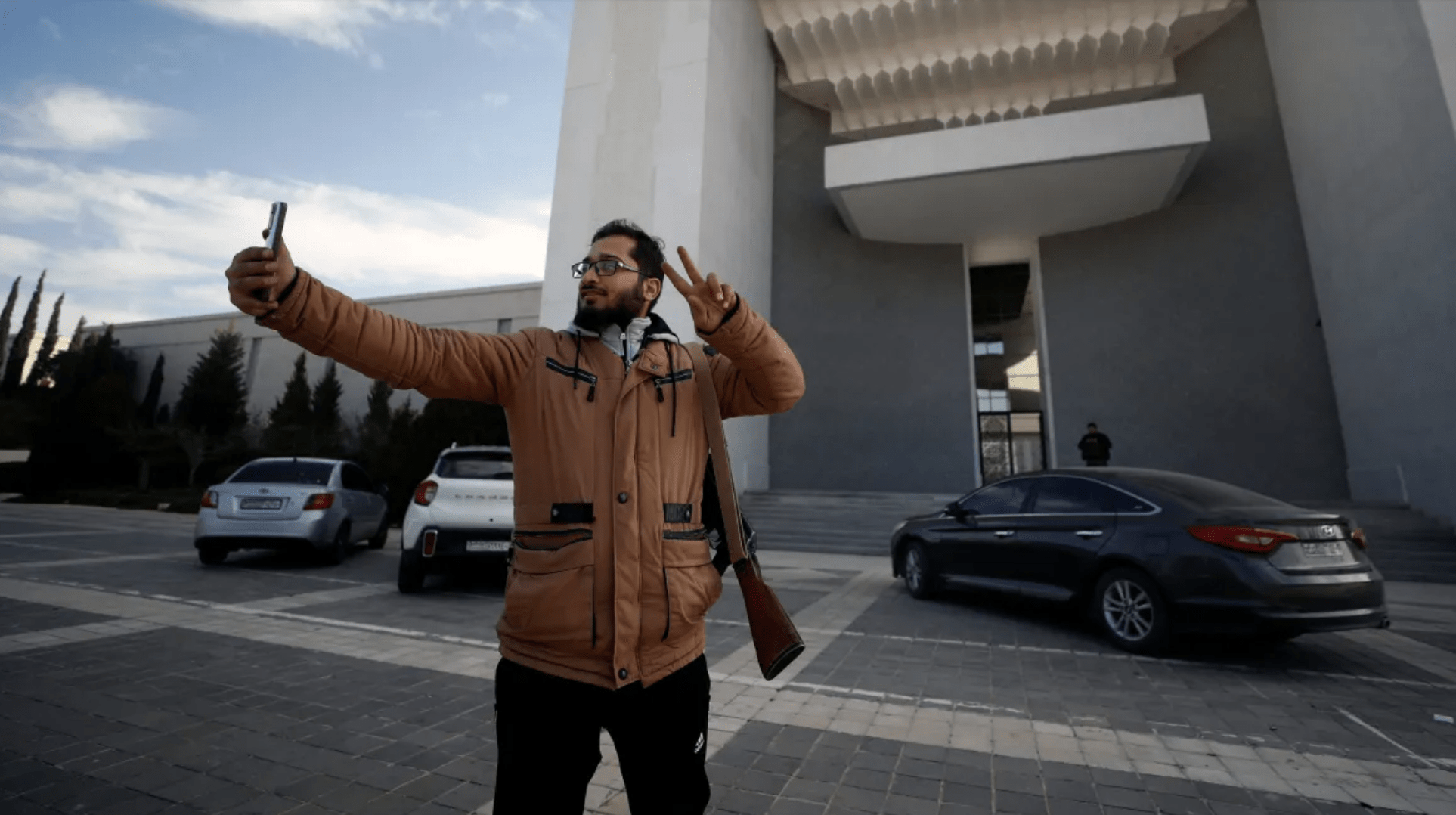

A Syrian opposition fighter takes a selfie at the abandoned presidential palace in Damascus, December 8/AP

A Syrian opposition fighter takes a selfie at the abandoned presidential palace in Damascus, December 8/AP

But the Syrian Army seemed near collapse. Only the Iran-supported Hezbollah fighters allied with Assad were at all effective. The ISIS fighters were steamrolling over the Syrian defenders and there were real prospects that the extremist and murderous Islamist State could imminently take Damascus and capture a real state for the first time, a nightmare for everybody else, including, incidentally, for Russia, which had its own problem with Islamist terrorism from Chechnya.

So, Russia intervened at Assad’s request, providing air-to-ground support that decimated ISIS forces exposed on open ground. While this act of intervention against the principal enemy, ISIS, was welcomed by the boots-on-the-ground-averse west, Russian attention pivoted to supporting the Syrian military against the non-ISIS insurgent forces, and against the civilian populations in the mostly Sunni cities that supported them.

The carnage was monumental. Of a population of around 22 million, over 600,000 died (1200 from chemical weapons). Fourteen million were displaced from their homes. Syria became the world’s largest refugee crisis: about 7 million fled the country, placing a harsh burden on Syria’s neighbours, Jordan, and Turkey especially. Canada, from 2015, welcomed roughly 45,000 Syrians who have become part of the country’s socioeconomic fabric. How many will choose to return to Syria will depend on what happens in the weeks and months to come.

The Syrian refugees also turbo-charged the wave of migrants hitting Europe (almost a million Syrian refugees in Germany alone), provoking the domestic nationalist right-wing opposition that sealed Brexit and whose parties are now forces of democratic destabilization across the continent.

Today’s Syria is a failed state: 90% live beneath the poverty line, and 7.2 million remain internally displaced.

The fall of Assad will enable some international humanitarian attention to reconstruct the country, but the massive rebuilding needs in Gaza and Ukraine are already extremely daunting.

However, this triumph in Syria – if it is real, and if it is genuinely a triumph of the people – sends a message of hope to repressed people everywhere. And it will remind Putin, Ayatollah Khamenei, Lukashenko, Burmese generals, and even Beijing, that people who can’t take it any more sooner or later, and often suddenly, do rise up and make history.

Policy Contributing Writer Jeremy Kinsman was Canada’s ambassador to Russia, high commissioner to the UK, ambassador to Italy and ambassador to the European Union. He is a Distinguished Fellow of the Canadian International Council.