Fewer Workers Means Fewer Homes: Fixing the Construction Labour Shortage

By Aftab Ahmed

October 7, 2024

The construction industry faces a twin problem: labour shortages and an impending wave of retirements. This is not a simple issue with an easy fix. It negatively affects four sequential components of the housing supply chain: workforce availability, the recruitment and retention of skilled labour, the development of housing projects, and the timely delivery of completed homes.

Fiscal policy measures – such as billions in housing investments – or regulatory reforms – like cutting red tape on zoning – will not succeed fully without ensuring there are enough workers to build the ambitious number of housing units needed to meet housing demand in the coming years. Statistics Canada indicates that the country continues to experience alarming losses in construction jobs, even as it consistently meets and exceeds its annual immigration targets. To be clear, the industry is not losing jobs per se: it is losing workers. The demand for labour remains high, but qualified and interested candidates are in short supply.

In 2023, CBC reported tens of thousands of unfilled construction jobs across Canada, including 20,000 in Ontario – a microcosm of a larger issue. Between June and July 2024, 45,000 jobs were lost – a sharp 2.8 percent drop – not due to falling labour demand but because more workers left than entered the industry. Construction, which historically contributes 7% to GDP during peak infrastructural booms, faces a wicked problem when factoring in retirements: 20% of its workforce is set to retire in the next decade.

Ontario, aiming to build 1.5 million homes by 2031, faces more than 80,000 retirements. Alberta expects to balance retirements through 2032, but British Columbia will lose 38,000 veteran builders without enough local recruits. Smaller provinces like New Brunswick expect 33% of workers to retire in four years, while Prince Edward Island’s need for construction workers doubled from 1,000 in 2022 to 2,000 by 2023.

There are just under 1.6 million construction workers across Canada, making up 8% of total employment, but pan-Canadian vacancy rates – open positions that cannot be filled due to a lack of skilled labour – remain at record highs. Writ large, the industry is offering higher pay, with wages rising faster than the overall economy, but people are still not seeking or taking the jobs to the extent required.

The bottom line: Construction-related labour shortages are a serious blow, first to Canada’s vision of increased production of high-demand infrastructure such as housing units across the board, and second, to its ability to implement that vision rapidly at a time when it is facing an affordability crisis driven partly by housing shortages, coinciding with sluggish growth trajectories and, as a result, necessitating a public policy need to design a more pro-economic growth ecosystem.

To be clear, the industry is not losing jobs per se: it is losing workers. The demand for labour remains high, but qualified and interested candidates are in short supply.

The two traditional sources of construction labour are local training institutions and immigration, but both are proving insufficient to meet the current crisis. The number of registered apprentices and trade qualifiers has dropped by 15% over the past decade. Although more women are entering the field, they represent 7% of apprentices, making this a vital yet underutilized source of construction labour. A closer look at recent policy incentives in a few Nordic countries, where women make more than 10% of the construction workforce, can offer lessons into how some European Union members are indeed exploring increased female participation as a tool to help close labour gaps.

Construction workers in Canada are typically hired through a combination of union recruitment, online job boards, and apprenticeship programs. Unions including the Labourers’ International Union of North America (LIUNA) play a leading role in connecting workers with contractors, especially for larger projects. Online platforms such as Indeed and LinkedIn are also widely used for hiring both skilled and general labour. Apprenticeship programs offered by trade schools are another major channel for bringing new entrants into the industry, providing a pathway for practical training and job placements.

Existing pools of refugees, asylum holders, and other marginalized groups, often overlooked for labour needs, including the unhoused and precariously housed, could also provide new entrants. Recruiting and training among these groups could open a Pandora’s box of complex, coordination-related discussions between different levels of government and require addressing factors beyond simply offering employment. But should they still be considered? The answer is yes. Zeroing in on these groups could address a twofold issue: creating pathways to well-paying jobs for vulnerable populations while tapping into existing labour potential within the country.

The other much-hyped source of labour – immigration – is falling short. Two percent of newcomers are entering construction-related careers, and that share has been declining over the past decade. British Columbia and Saskatchewan have the highest shares of immigrants joining the industry, but even these provinces struggle to meet demand. This is worrying, as immigrants generally participate in the labour market at higher rates than those born in Canada.

Programs such as the Express Entry have failed to attract enough workers towards the construction industry. Notwithstanding recent changes aimed at incentivizing immigration in skilled trades, newcomer interest in construction remains very low. In principle, however, Immigration Minister Marc Miller has been clear: Canada’s housing crisis cannot be solved without new immigrants, signaling a need for better policy integration between immigration and housing strategies.

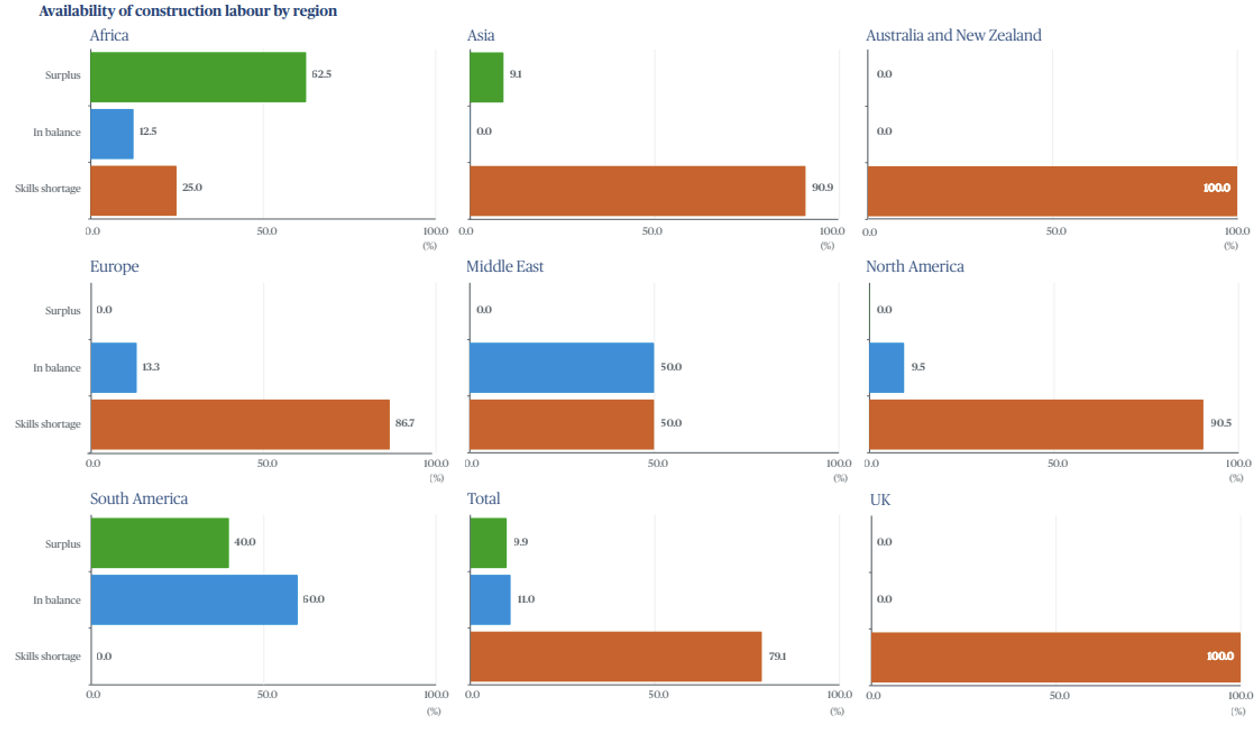

Turner and Townsend’s 2024 International Construction Market Survey (per above) indicates that the issue of construction-related labor shortages is not confined to Canada. Most developed economies are dealing with a scarcity of skilled construction workers, driven by an aging workforce, high retirement rates, and a lack of young recruits entering the industry.

In Canada, temporary foreign workers have helped fill some gaps, with about 11% employed in construction. Many of the estimated 500,000 undocumented residents in Canada also work in construction, having initially entered the country legally but later lost their immigration status due to issues with student visas, temporary work permits, or asylum claims. To internalize this externality, Ottawa doubled the number of out-of-status construction workers in the Greater Toronto Area eligible for permanent residency through a temporary immigration pathway.

Public pressure to tackle what many have deemed unrestrained immigration numbers has become a focus in today’s hostile and often cutthroat political discourse. Leveraging the temporary foreign worker channel no longer seems to be on the immediate agenda, with Ottawa cutting back on its preference for these workers due to concerns about exploitation within the construction industry, combined with political realities. At worst, these realities reflect a reactionary, knee-jerk response where newcomers are politically scapegoated to leverage financial anxiety, as has been done throughout history without much evidence, and at best, they represent a necessary pulse check on federal immigration policy.

The issue boils down to five big-picture takeaways. First, labour shortages are worsening the ongoing housing crisis, as the lack of workers limits the construction industry’s ability to meet the increasing demand for new homes, further deepening the supply problem. Second, these shortages are a pan-Canadian issue, with most jurisdictions facing delayed or stalled housing projects, though the severity varies by region.

Third, despite competitive wages, construction jobs remain unappealing to many younger workers raised in a digital world, causing a disconnect between pay and the willingness to take on these roles, leaving thousands of well-paying positions vacant. Fourth, with an aging workforce, the overall situation is poised to deteriorate further, as retirements outpace recruitment, creating human resource limitations for the industry’s ability to meet housing demand. Finally, immigration has not provided the expected relief to construction-related labour shortages, raising doubts about its ability to ease the issue, as too few newcomers are entering skilled trades.

The recently published Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s Fall 2024 Housing Supply Report echoes the above takeaways. Housing starts across the six largest census metropolitan areas rose by 4% in the first half of 2024 compared to the same period in 2023, marking the second strongest level of new construction since 1990. When adjusted for population growth, this increase was insufficient to meet the growing demographic demand.

Industries should have a stronger voice in setting newcomer skills and targets to align labour market needs with immigration policies.

In Ontario, housing starts fell by 13 percent, largely due to labor shortages and rising construction costs, particularly in the purpose-built rental sector. British Columbia faces similar challenges, with tight labor markets slowing housing production, especially in urban areas like Vancouver, where developers struggle to meet pre-construction sales targets. Alberta, however, saw growth in housing starts, especially in Calgary and Edmonton, driven by strong labor availability and interprovincial migration. Beyond labor shortages, high construction costs, regulatory barriers, and financing difficulties also hinder housing supply, with Vancouver seeing a drop in multi-unit starts due to rising land and development costs. The report warns that retirements will further strain the industry unless labor supply is strategically increased.

What are the solutions? There are domestic tools that should be considered by looking beyond the current generation of labour and applying greater public policy thought to the next generation of workers. Incentivizing — not just encouraging through rhetoric — school-aged students to pursue careers in trades, increasing women’s participation, and recognizing underemployed and vulnerable individuals as valuable sources of labour are areas that should be pursued through an outcome-focused public policy outlook.

On the newcomer front, Canada needs to take a step back and define what it wants to achieve through its immigration system and do so without thinking of immigration in a silo. It must rank in order of precedence whether it seeks to attract international students to strengthen a marquee economic driver in its higher education sector, skilled labour to fill unskilled jobs, or establish an extremely well-thought-out channel to meet specific and evidence-based labour needs.

If the last option is the priority, then two things may be considered as starting points: First, the Express Entry system must strategically reduce its bias toward post-secondary qualifications for newcomers and prioritize candidates with skills that match domestic labour needs and communicate this clearly to applicants. Second, industries should have a stronger voice in setting newcomer skills and targets to align labour market needs with immigration policies.

Since 2023, Ottawa has been taking steps in the right direction. First, Sean Fraser revamped the Express Entry system last year to focus specifically on candidates with skilled labour experience, aiming to create a clearer path to permanent residency for tradespeople like carpenters and plumbers. Second, Marc Miller introduced a trades-focused standalone category this August under the Express Entry system. Third, Ottawa is currently assessing the feasibility of tying Post-Graduation Work Permits to high-demand educational programs in skilled trades and other labour-need-specific professions to incentivize international student graduates to enter the workforce where they are most needed.

On the diplomatic front, direct outreach to Asian countries with remittance-driven economies – such as Bangladesh, the Philippines, Pakistan, and Nepal – should be considered. Canadian embassies and high commissions could be tasked with promoting labour-focused immigration pathways, aligning with the Indo-Pacific Strategy’s stated objective of providing pathways to jobs and permanent residency to meet domestic labour needs. Communicating Ottawa’s evolving immigration priorities to foreign governments, followed by penning labour-specific bilateral agreements, can help Canada leverage immigration better as a tool to meet the projected need for over 500,000 additional construction workers by 2030.

Policy Contributing Writer Aftab Ahmed graduated with a Master of Public Policy degree from the Max Bell School at McGill University. He is a columnist for the Bangladeshi newspapers The Daily Star and Dhaka Tribune, and his opinion pieces have been featured in Canadian outlets such as the Globe and Mail, Hill Times, Policy Options, and the Line. He is currently a Policy Development Officer with the City of Toronto.

The views expressed in this article are personal opinions and do not reflect the views or opinions of any organization, institution, or entity associated with the author.