Faster, Lower, Stranger

By Douglas Porter

July 26, 2024

Waltzing back into the office after almost two weeks off, so tell me, did anything much happen? Markets appear to be almost as discombobulated by the whirlwind of recent political developments in the past month as someone just emerging from a cave in Kyrgyzstan. After spending the first six months of the year calmly handicapping a set-piece replay of the 2020 U.S. election, investors are suddenly facing a new and unfamiliar political landscape, and the volatile day-to-day swings suggest they are struggling to make sense of it all. Meanwhile, rumbling away in the background, the economy isn’t making things clearer: heavily conflicting signs are emerging with seemingly each and every indicator. The net result has not been entirely pretty. The S&P 500 dropped almost 5% from its mid-July peak before a big Friday bounce, and the mighty, mighty Nasdaq slid nearly 8% from its recent lofty perch.

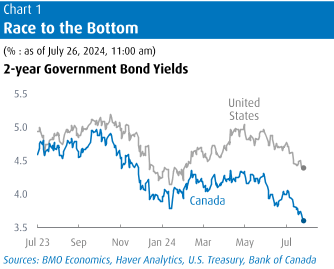

On the contrary, bonds are somewhat enjoying the chaos. After initially rocketing to almost 4.5% on the so-called Trump Trade, the 10-year Treasury yield has dropped back to around 4.2%. More notably, the 2-year yield has plunged by more than 50 bps in the past two months to less than 4.4%, moving within shouting distance of 10s. At one point this week the 2s-10s curve came within less than 10 bps of dis-inverting for the first time since the spring of 2022. The furious rally at the short end reflects the growing conviction that the Fed is getting locked and loaded to begin cutting rates. Next week’s FOMC is widely expected to set the stage for a September cut, with at least a few prominent commentators now calling for a move forthwith, with haste.

It increasingly appears that a September rate cut could be the start of a series of such moves. We have long called for a gradual and leisurely step down the interest rate staircase, with a trim in September, then a pause, then a cut in December, then a pause, then perhaps a cut… you get the picture. Markets are instead now mostly looking at a steady stream of cuts, with some chatter about the possibility of 50 bp moves sprinkled in, should the U.S. job market buckle. We would note, however, that from the very day the Fed began hiking rates in March/22, the major market mistake has been to price in rate cuts too early and too aggressively. So, while we are close to getting on board with a faster set of rate cuts, we’ll await clearer evidence from the data before adjusting our call.

The two major indicators this week didn’t really help the rate cut cause, but they didn’t set it back either. The first estimate of Q2 real GDP landed squarely on the high side of expectations at 2.8%, or double the sluggish Q1 reading. The average of the two quarters (2.1%) is probably a truer measure of the underlying pace of the economy, but it’s far from weak. In fact, the U.S. economy has grown at precisely a 2.1% annualized rate since the start of this century. Even amid a variety of signs of softening activity, the broadest measures—GDP and jobs—aren’t pointing to serious stress just yet. Still, the weight of more recent indicators, both survey data and hard readings, suggest that activity will chill in the second half. On the inflation front, this week’s other important indicator revealed that core PCE inflation was steady in June at 2.6% y/y, with prices up an okay 0.2% in the month. After a fiery start to 2024, the three-month trend has since ebbed to an acceptable 2.3% a.r., likely low enough to give the Fed comfort and an amber light for rate cuts—that is, proceed with caution.

Caution is not the word we would associate with the Bank of Canada’s verbiage surrounding their second rate cut of the cycle. Joining only the Swiss National Bank in the two-cut camp, the BoC met expectations with its 25 bp trim this week, taking the overnight rate down to 4.5%. But, for the second decision in a row, the move was accompanied by surprisingly dovish language. Leaving little to the imagination about its intentions, the Bank fretted about downside risks, even warning that inflation could go too low for comfort. (We would sternly advise Bank officials against using that line when next mingling at the grocery store and/or gas station.) Governor Macklem openly talked about the need to get growth going again, and specifically cited the 6.4% unemployment rate. He also again said that the rate differential with the U.S.—now 87.5 bps below the mid-point of the Fed funds target—is not close to its limit. We’re calling for two more cuts this year, and then a gradual decline in 2025; the risk is clearly for more and faster.

Bonds thrived on the Bank’s mild message. The two-year GOC yield fell below 3.6% for the first time since the spring of 2023, in the aftermath of the SVB collapse. Yields are now down by more than 100 bps from a year ago, when the Bank was last hiking rates. But the Canadian dollar was less than enthused by the news. The widening gap with U.S. rates has cut the loonie to the low-72 cent zone (or above $1.38/US$), and it appears quite vulnerable to any bad news. The only thing keeping the currency from seriously swooning is the growing expectation of the Fed soon joining the rate cut parade. In contrast, the TSX was a quiet outperformer amid the volatility elsewhere in global equities. After woefully lagging in the first half of the year, the index is on track for a fifth weekly rise in a row, benefitting from some serious rotation among sectors, back to safety and/or rate sensitives and away (for now) from the highest of the high-fliers. The BoC’s stark dovish turn this week certainly did not hurt.

As much as we would love to weigh in on the possible economic implications of the past week’s political earthquake, let’s all just stand back for a moment and take a breath. The election is still more than 100 days away. First, we need to see who the presumptive Democratic nominee Harris chooses as a running mate. And, then, let’s see how the dust settles in the polls after the Democrats’ convention in the third week of August. But, at the very least, we now know that we’ve got a competitive race again, and that now includes the House and perhaps even the Senate. Of the eight different possibilities that could emerge from the combination of President, House and Senate, four are quite believable, including full-on sweeps, which of course have completely different implications. However, the one morsel of advice we would offer is beware of the national polls, and not just because it’s really only the 7-8 battleground states that will decide this thing. Note that in 2016, the final popular vote tally read Clinton 48.2% to Trump 46.1%, a 2.1 ppt gap; yet the latter won 55% of the Electoral College.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.