Exploring the Arctic, and Climate Activism

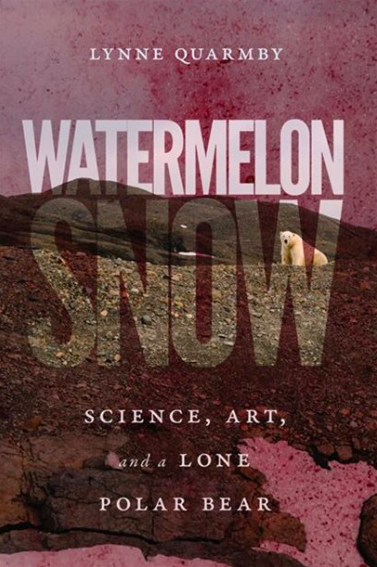

Watermelon Snow—Science, Art and a Lone Polar Bear

McGill-Queen’s University Press, October, 2020

By Lynne Quarmby

Reviewed by Dan Woynillowicz

November 2, 2020

I have a confession to make. After spending the better part of two decades as an advocate working to raise public awareness, offer policy solutions and enable the necessary political courage to tackle climate change, I don’t often read books on the subject anymore. Day in and day out, I follow the never-ending stream of scientific evidence, the news cycles documenting tragedies of those already suffering the consequences of climate change, and the seemingly detached response from political and business leaders. I’m acutely attuned to the magnitude of the threat and the all-too-slow progress we’re making to address it.

But I’m glad I read Watermelon Snow, by Lynne Quarmby. In a deeply personal memoir, Quarmby — chair of the Department of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry at Simon Fraser University — weaves together two journeys, a voyage with the group Arctic Circle aboard a schooner full of artists-in-residence, and her evolution from scientist to climate change activist to would-be-politician.

Within the first few pages, one feels, viscerally, Quarmby’s sense of despair: that, having poured her soul into the work of climate advocacy, “We have barely made a dent in altering the course of ‘business as usual.” And so, in 2017 she found herself on a boat, the Antigua, halfway between Norway and the North Pole, with 28 artists and two scientists (including herself), in search of “rational, meaningful responses to the global environmental crisis, a search for life beyond despair.”

What follows is the story of her 15 days exploring Arctic waters, bearing witness to the accelerated melt, the calving of icebergs and the abundance of life, from microscopic algae (her research focus) to the increasingly threatened polar bear. As readers, we get to experience this journey not only through her eyes, but through her recounting of the artistry of her shipmates, whose creative interpretations offer vantage points beyond the scientific.

Chapters documenting her Arctic journey are interspersed with Quarmby’s scientific journey — from Darwin to deep red snow algae blooms— “watermelon snow,” the book’s namesake. She also leads us through her discovery of climate change as an existential issue (in a German science museum), and the cascading events that took her from her university laboratory to the frontlines of anti-pipeline protest, arrests, and court dates.

Left unexplored are the myriad pragmatism-vs-perfection reasons why “keeping it in the ground” is such a hard sell: the contribution fossil fuel extraction has made to Canada’s economy, the jobs and livelihoods that depend upon it, and the inherent challenge of building a national consensus in a fractured federation.

Throughout the book, one can’t help but be struck by just how much despair Quarmby feels in the face of climate change: “I struggle to embrace the truth. I’m overwhelmed by frustration, anger and discouragement.” And even when not stated so explicitly, these feelings are implicit throughout. Yet while she laments that her climate activism has not been more effective, she doesn’t delve into why that might be, beyond pointing at greedy corporations and weak-willed politicians.

Left unexplored are the myriad pragmatism-vs-perfection reasons why “keeping it in the ground” is such a hard sell: the contribution fossil fuel extraction has made to Canada’s economy, the jobs and livelihoods that depend upon it, and the inherent challenge of building a national consensus in a fractured federation.

The chapters documenting her role as an activist — first blocking trains moving thermal coal to Pacific ports, and then protesting the expansion of the TransMountain pipeline — and Green candidate in the 2015 federal election, make clear how deeply she feels about climate change. The anger and burnout both mask, as she later reveals, a deeper anguish about all that has already been lost, and all that stands to be lost.

The federal government’s approval and eventual ownership of the TransMountain pipeline is seen by Quarmby as an unconscionable act, and proof that our political leaders neither understand nor care about climate change. Consequently, and to its detriment, nowhere in the book is there any acknowledgment of this same government’s climate policy progress: a legislated phase-out of coal-fired power, a national price on carbon pollution, programs to support adoption of electric cars and foster innovative climate solutions, to name just a few. It was a worrying sign of a tunnel vision that, in my observation, often does more to degrade than encourage the convening of a broad coalition of Canadians that will call for, vote for, and hold accountable, the political leadership we need to ward off the worst impacts of climate change, and find opportunities in solutions.

As Quarmby comes to acknowledge after her Arctic journey, “It will take me another year to appreciate that I am dealing with something bigger than recovery from burnout — that I need to learn how to live with a grief I haven’t yet had the courage to face.” As someone who has worked in and around the environmental movement for 20 years, I recognize both these symptoms and underlying cause. I have seen too many bright, passionate and committed environmentalists crushed by the weight of unmet expectations, and all too often they end up drifting away.

In the concluding chapters, Quarmby zooms out to the bigger picture. She seeks out hope in the writing of Rebecca Solnit, who writes, “Despair is often premature: it’s a form of impatience, as well as of certainty,” and the examples set by young activist friends, whom she counts as the happiest people she knows. Potential solutions are touched on only briefly, but it’s clear she’s seeking them.

The table stakes, which this book makes evident, are clear: “We’re facing radical changes in our weather systems, with severe impacts on human civilization. It’s happening now and it will continue to get worse. How fast it gets worse and how bad it gets is up to us.”

For those of us with children, there is an added weight. As Quarmby’s son Jacob says to her at one point, “There is nothing you could do for my future that is more important than this.” The challenge, then, is to walk the line between hope and despair.

Watermelon Snow is a moving book, eloquently dancing between the science and emotion that defines life in a warming world, and offers a glimpse at what we must overcome if we are to soldier on in search of solutions.

Dan Woynillowicz is the Principal of Polaris Strategy + Insight, a public policy consulting firm focused on climate change and the energy transition.