Elizabeth Warren and the Hippocratic Hatch

In a year when American voters are longing for both change and normalcy, electability trumps all other arguments.

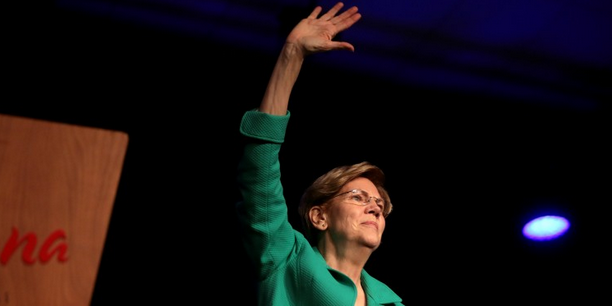

Flickr photograph by Gage Skidmore

Flickr photograph by Gage Skidmore

Lisa Van Dusen/For the Hill Times

March 12, 2020

When Elizabeth Warren announced her withdrawal from the Democratic presidential primary last week, she included a shout-out to all the young girls she’d met along selfie lines whom she’d generously left with the verbal memento, “I’m running for president because that’s what girls do.”

“All those little girls who are going to have to wait four more years,” Warren told reporters gathered outside her home in Cambridge, Mass., March 5, her voice cracking. “That’s going to be hard.”

What Warren, on reflection, might have wanted to say was that when you run for president, there are no guarantees, and that the important thing is giving it your best shot. She probably didn’t intend to tell little girls that running for president is what girls do and then tell them she lost because she’s a girl.

As Warren herself said that day, sexism clearly persists in politics, especially when competing for the most powerful office in the world. This obviously puts women at a disadvantage, especially against their white male counterparts who start any campaign unburdened by the asterisk attached to any identity that isn’t white and male.

Anybody who is not a white male running in the context of a reality that still includes racism and sexism has to—and we can bemoan the unfairness of this until we all have infarctions, but it’s true—first do no harm in order to neutralize that obstacle. There may be a glass ceiling, but it contains a hatch.

It’s what Barack Obama did in 2008. Everything he said and did—even the things he said and did to move past things he shouldn’t have said or done—included more people, excluded fewer people, and aimed at making sure that as few people as possible had a plausible, rational reason to not vote for him. That process gradually isolated racism as a factor in voter intention, and his momentum after the financial crash made any vestige of it seem even more preposterous given that he was already pretty much performing as president-in-waiting.

It wasn’t a well-curated exercise in misrepresentation. It didn’t rely on a propaganda machine designed to silence and punish critics. It didn’t industrialize dirty tricks. And it didn’t assume voters were stupid or scared enough to buy what the candidate was selling despite their better instincts rather than because of them.

Warren possesses all the positives of Obama in terms of character, authenticity, intellect, trust, and relatability, but tilted more toward subtraction than addition with her $20-trillion health care plan and $1.25-trillion free college plan likely culling more voters who were sticklers for reason and implementability than ideology. Warren may have run a great campaign on many fronts, but her brand as a master of policy—one of the things that broadened her appeal—was a precarious commodity.

Once Joe Biden’s national electability—which until South Carolina hadn’t really been tested with actual voters—met the overwhelming yearning to be rid of Trump, Warren’s strategic weaknesses likely contributed more to her Super Tuesday showing than her gender did.

To think that Warren, who proved her status as a national treasure on Saturday Night Live two days after withdrawing, did not prevail in the primaries only because she’s a woman, or that Clinton lost in 2016 only because she’s a woman, is to ignore a cocktail of other factors involving strategy, policy, character, and timing that would have been impediments to any candidate.

Warren may yet be the first woman to prove that being president is what girls do when they win. With the same calibration of integrity, honesty, authenticity, skill, and strategy that allows African-American kids to now say, “Being president of the United States is what we do.”

Lisa Van Dusen is associate editor of Policy Magazine and a columnist for The Hill Times. She was Washington bureau chief for Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News, and an editor at AP in New York and UPI in Washington.