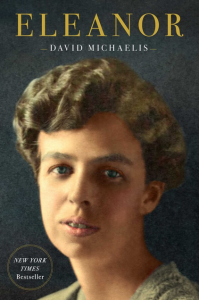

Eleanor Roosevelt: From Cloistered Girl to Global Rights Champion

By David Michaelis

Simon & Schuster/2020

Review by Rosalie Silberman Abella

January 10, 2021

I’ve always found that one the most fascinating aspects of biographies of “famous” people is how often their childhoods were marinated in unhappiness, loss or failure. The process of transcending these traumatic anchors and enjoying a productive adulthood usually reflects resilience, forbearance and serendipity.

Eleanor Roosevelt was no exception. She emerged triumphantly singular from the insularity of Oyster Bay and Edith Wharton’s New York, two worlds guided by “ought to” rather than “want to”. Unless you were male, in which case you could usually do what you wanted to because it was quietly tolerated by a social code that protected its own from reputational damage and thrived on the permissive air of entitlement.

According to David Michaelis, Eleanor’s latest attentive biographer, the Oyster Bay Roosevelts had, above all other impulses, “the resolve to transform private misfortune into public well-being”. Throughout her life, both were her frequent companions. She adored her father, Elliott Roosevelt, brother of the intrepid Theodore, but despite the adoration he returned, he was intermittently present and when he was, often incapacitated by alcohol, or distracted by his financial and extra-marital missteps. Eventually his forays into disgrace could no longer be hidden, but no one shared them with Eleanor. With a mother who ignored or humiliated her relentlessly, he remained the man she lived to please until he died when she was ten.

She moved to her grandmother’s house, where she was further trained in the expectations for “wellborn” girls of her generation to be “mistress of a household”. She seemed to “need only to please, and to be good, strong and brave for others”, including for her younger brothers. Her nearest companions were books and some relatives who excelled at the lifestyle of the “idle rich”. Yet her heavy sense of duty remained sturdy, and she coped with her insecurities by making herself “more or less invisible”.

Two events transformed her. The first was Allenswood, a bilingual academy outside Paris run by a highly cultured and worldly woman, Marie Souvestre. Souvestre mentored Eleanor, nurtured her confidence, and planted the seeds that would grow her aspirations beyond the borders marked by her grandmother’s admonition that “All you need, child, are a few social graces to see you through life.”

The second transformative event was her marriage to her distant cousin Franklin Delano Roosevelt, a merger of Hyde Park and Oyster Bay, one family but different worlds. Much has been written about Eleanor’s role in helping her resolutely ambitious husband when he became the navy’s youngest assistant secretary, then governor of New York, then president; about her challenging relationship with his ever-present mother; about her indispensable role in his rehabilitation after his shocking polio diagnosis; about her unquestioning acceptance of the bigotries of the day – antisemitism, (she described Felix Frankfurter as “an interesting little man, but very Jew”), racial segregation, and women’s roles (she was originally against women having the right to vote); and about her growing recognition and acceptance that their marriage was based more on mutual respect than on romantic love. But it remains riveting to read about her evolutionary shedding of the skin of Wharton’s Brownstone Society, and blossoming into a national and global leader who shattered stereotypes and delivered fairness for women, workers, immigrants, minorities, and children.

It started in earnest in 1917. In her words “The war was my emancipation and my education”. And what an emancipation it was! She became active in the American Red Cross, The New York League of Women Voters, and The Women’s City Club of New York as legislative director advocating for child labour laws, worker’s compensation, literacy, and legalized birth control for married couples. She got a voice of her own when she became chair of the Women’s Division of the Democratic Party, broadening her social and religious network. She supported the League of Nations and the World Court of Justice, and championed better housing for the poor and aging, help for Southern tenant farmers, and reforms to working hours and wages.

She took on Tammany Hall, Bull Connor and Father Coughlin. She joined the Washington, D.C. chapter of the NAACP, and opposed segregated public schools. In 1939, when the Daughters of the American Revolution banned the Black contralto Marian Anderson from giving an Easter Concert in Constitution Hall, she resigned from their organization and invited Anderson to sing at the White House for the King and Queen of England. She travelled extensively across America and visited foreign countries by herself to assess their social and economic conditions — a first for a president’s wife — and all with the president’s approval. She travelled so much that a Washington Post headline in 1934 trumpeted: “First Lady Spends Night in White House”. During the Second World War, she vigorously opposed the shameful internship of Japanese Americans under Executive Order 9066, warning that:

“If we cannot meet the challenge of really believing in the Bill of Rights and make it a reality for all loyal American citizens, regardless of race, creed or color; if we cannot keep in check anti-Semitism, anti-racial feelings, as well as anti-religious feelings, then we shall have removed from the world, the one real hope for the future on which all humanity must now rely.”

She became, as Time magazine noted, “a woman of unequaled influence, superlative in her own personal right” and, as Michaelis notes, the “advocate for the voiceless”.

When his staff would urgently ask him to ask her to stop generating controversy over these issues, the President shrugged it off, saying it would “blow over”. When Eleanor asked him how he felt about her contrary stance on some legislation he supported, he said “you go right ahead and stand for whatever you feel is right.” She had come a long way from his Inauguration Day as New York Governor in 1929, when she told a reporter: “I don’t exactly know what is before me, but I expect to solve problems as they come along. That has always been my way and things always get done.”.

She kept getting things done even after her husband died in 1945, participating, at President Harry Truman’s request, in the creation of the United Nations, accepting an appointment as chair of the UN Human Rights Commission, and reifying the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, becoming the world’s foremost champion of human rights. It is hard to argue with the moniker H. L. Mencken gave her when he said she was “the most influential female ever recorded in American history.”

Her private life was complicated. The book extensively chronicles her loving relationship with the journalist Lorena Hicks, her husband’s with Lucy Mercer, her familial disappointments, and her omnisciently disapproving mother-in-law. Yet none of it blocked her courage. Brought up in a world that embraced the status quo, she embraced change. Trained to serve her household, she served her country instead. Told that women were silent marital adjuncts, she became her husband’s closest and most vocal advisor — and the most famous feminist in the world.

All this and more is chronologically delineated in this engrossing book. The degree of detail can sometimes get in the way of the narrative flow, but it’s worth the effort because by the end, all the pieces fit perfectly and luminously reveal the astonishing story of Eleanor Roosevelt’s metamorphosis from a compliant woman of her times into a woman who reshaped them.

Of all the mesmerizing details in the book, one struck a personal chord. During the Second World War, she had “made it her mission to save as many Jewish European children as she could”, along with pressuring an unreceptive State Department to expedite 4,000 visitors’ visas for Jewish refugees including Marc Chagall, Max Ernst, Hannah Arendt, André Breton and Marcel Duchamp. Near the war’s end, on April 16, 1945, the day after President Roosevelt died, Edward R. Murrow broadcast the first eyewitness account of a Nazi concentration camp, Buchenwald. Neither he, nor Time or Life magazines which reported several days later from Dachau, identified the victims as Jewish. It took Eleanor Roosevelt in her column, at the end of that month to admonish: “Are our memories so short that we do not recall how in Germany this unparalleled barbarism started by discrimination directed at the Jewish people?”

She decided to visit some Displaced Persons Camps in Germany to see the state of the Jewish survivors for herself. In 1948, she visited the one in Stuttgart, where my father Jacob Silberman, a lawyer, was head of the D. P. Camp. He introduced her by calling her “the protector of human rights, fighter for freedom, peace and justice” and added: “You, Mrs. Roosevelt, are the representative of a great nation, whose victorious army liberated from death the remnants of European Jewry and highly contributed to their moral and physical rehabilitation… We are not any longer in a position of showing you here assets such as factories, farms, establishments and the like. The best we are able to produce are these few children. They alone are our fortune and our sole hope for the future”.

I was one of those children.

Justice Abella is on the Supreme Court of Canada.