Ed Broadbent, Improbable Giant of Social Democracy

The years during which Ed Broadbent led the New Democratic Party — 1975 to 1989 — saw some of Canada’s most consequential debates and existential inflection points. When he retired, Broadbent led the International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development and founded the Broadbent Institute. Now, as longtime NDP strategist and policy advisor Robin Sears writes, Broadbent is turning to his legacy as an advocate for social justice and equality.

* This piece was first published in March 2022, and has been re-posted on January 11, 2024, on the news of Ed Broadbent’s passing.

Robin V. Sears

It was a very formal state occasion marred by a little rain, but blessed by the presence of the Queen. It was also the victors’ celebration of a two-year constitutional political war. One of the most bitter political struggles in Canadian history, it teetered on the brink of failure several times. April 17, 1982 saw the Queen formalize Canada’s constitutional patriation in the form of the blandly titled “Constitution Act”. The outdoor signing ceremony on Parliament Hill included that indelible image of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and Queen Elizabeth — in her teal coat and hat — at a Regency signing table, enacting a peaceful if blustery post-colonial transfer of power.

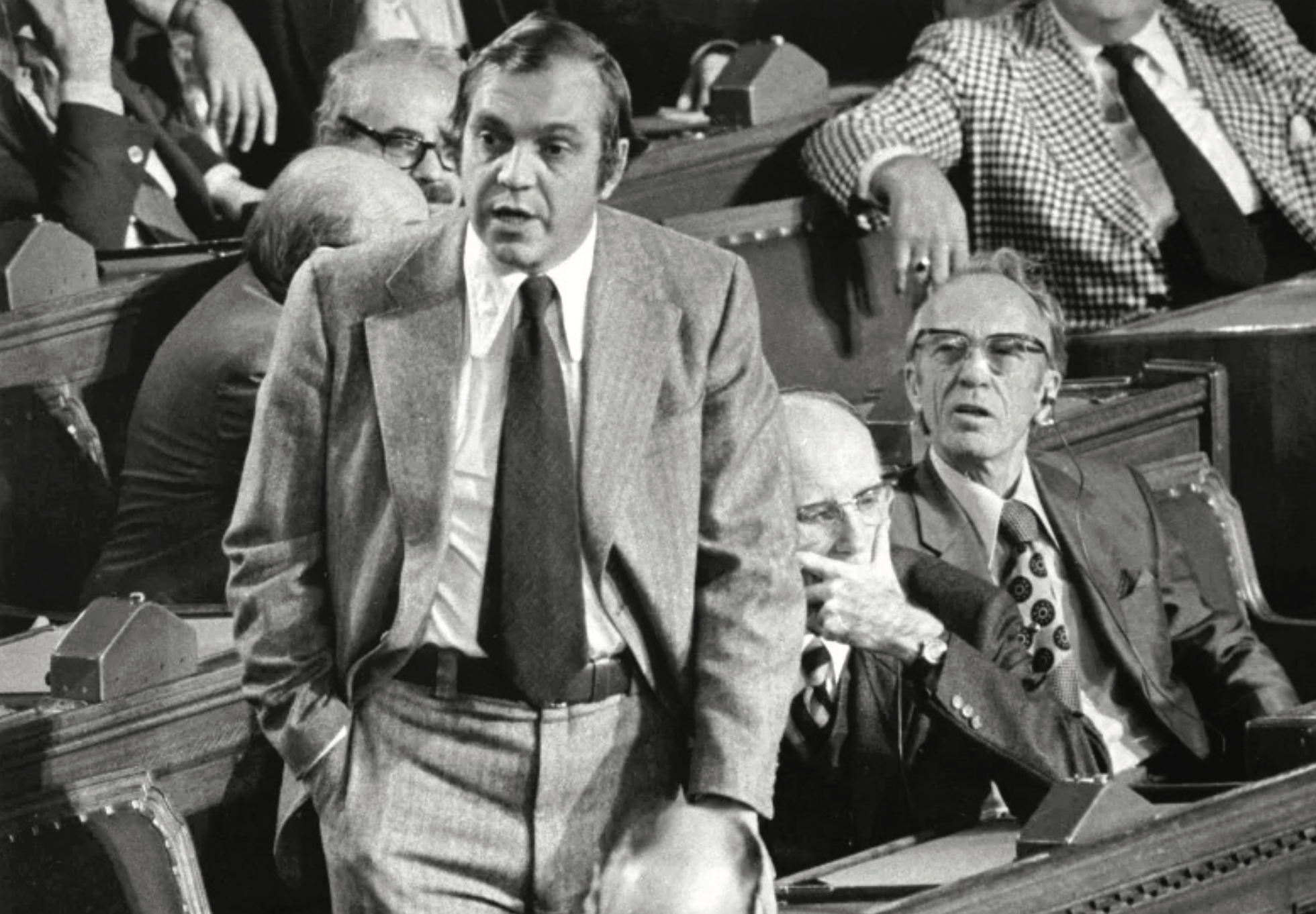

Hundreds of Canada’s high and mighty had maneuvered for a place at this momentous occasion, with hierarchy and precedence the order of the day. As the political leaders — premiers, parliamentarians, ministers current and former — lined up to greet the Queen, Ed Broadbent fell in behind the prime minister, but ahead of all the provincial premiers. Only insiders spotted this visible breach in protocol. As the leader of the third party in the House, he should not have been given such precedence.

But as he passed Pierre Trudeau, the triumphant prime minister gave Broadbent a knowing smile. As Broadbent recalled nearly 40 years later, “Pierre was not so great at thank yous, but this was his way of saying thanks to me for the tough battle we had fought together — along with naming me to the Privy Council.”

Winning the passage of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the first constitutional recognition of Indigenous rights and women’s equality rights, was indeed Broadbent’s achievement almost as much as Trudeau’s. Every comma of Section 35 on Indigenous rights was hammered out in long tough meetings in his office, jammed with First Nations leaders from across Canada. Trudeau was vigorously opposed to it, as he had spent his life fighting “special rights” for any group. It was Broadbent who made him understand he had to swallow hard if he wanted a deal. It is no exaggeration to say that if Broadbent had not put his leadership of the NDP on the line at risk of a permanent split in the party, the Charter and the Constitution itself it would not have happened.

Flash-forward three decades to May 7, 2011, and a suite at the Hotel Saskatchewan in Regina, less than a week after the stunning election triumph that Jack Layton had delivered his party in winning 103 seats and Official Opposition status. The very emotional memorial service for Allan Blakeney, one the greatest premiers of his generation who had died a few weeks earlier, was over. Old friends gathered in the rooms of his successor as NDP premier, Roy Romanow, to reminisce and reflect. As one of the participants, Brad Lavigne, put it, “So there we were, in the very cradle of the party, mourning the loss of one of our giants, while still glowing from our incredible election victory. Sitting with Ed Broadbent, Roy, Bill Knight (a Saskatchewan MP and longtime Broadbent friend), Brian Topp, (a former aide to Blakeney and a key Layton political operative). You could feel the history and power of the moment.”

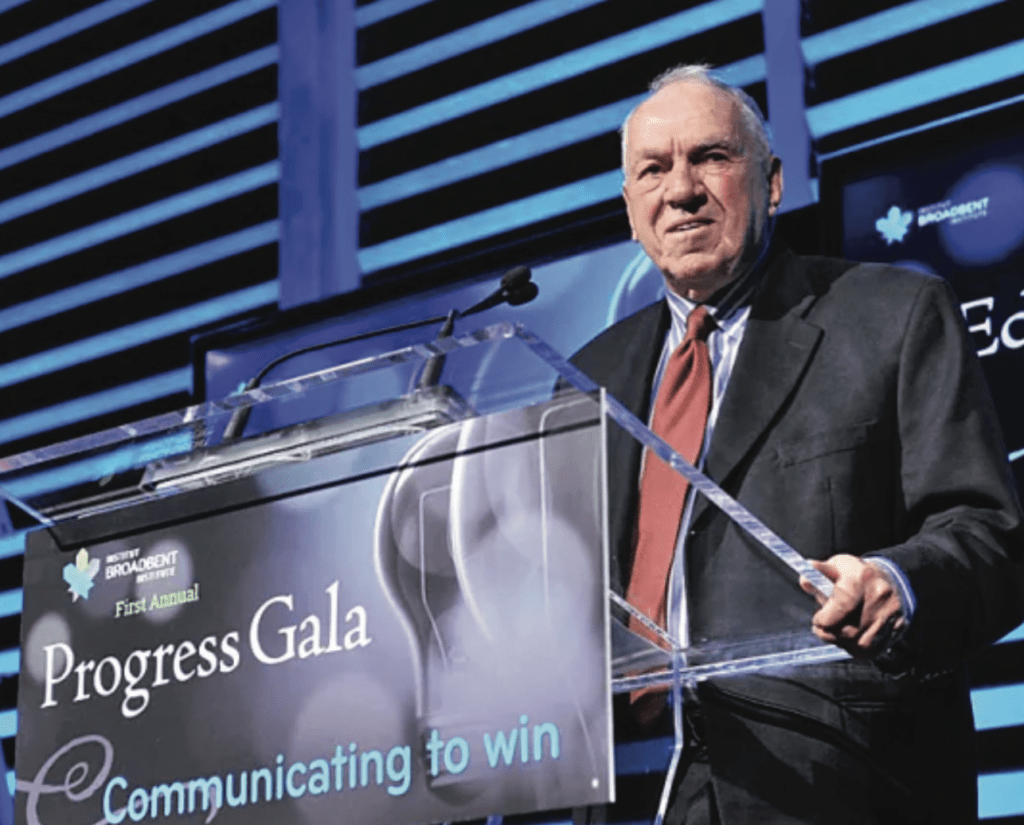

Lavigne decided it was precisely the occasion to raise a long-held dream he had been nurturing: a social-democratic counter to the Manning Centre and the Fraser Institute. He had put it on his list of ‘must-do’s’ when he had taken over as the party’s national director under Jack Layton. But it hadn’t got done. That night it did. Lavigne knew that right-wing conservative messengers were getting their narrative into the public domain through their think tanks, their media allies and their tame academics. The Manning Centre and the Harper government had accelerated the phenomenon.

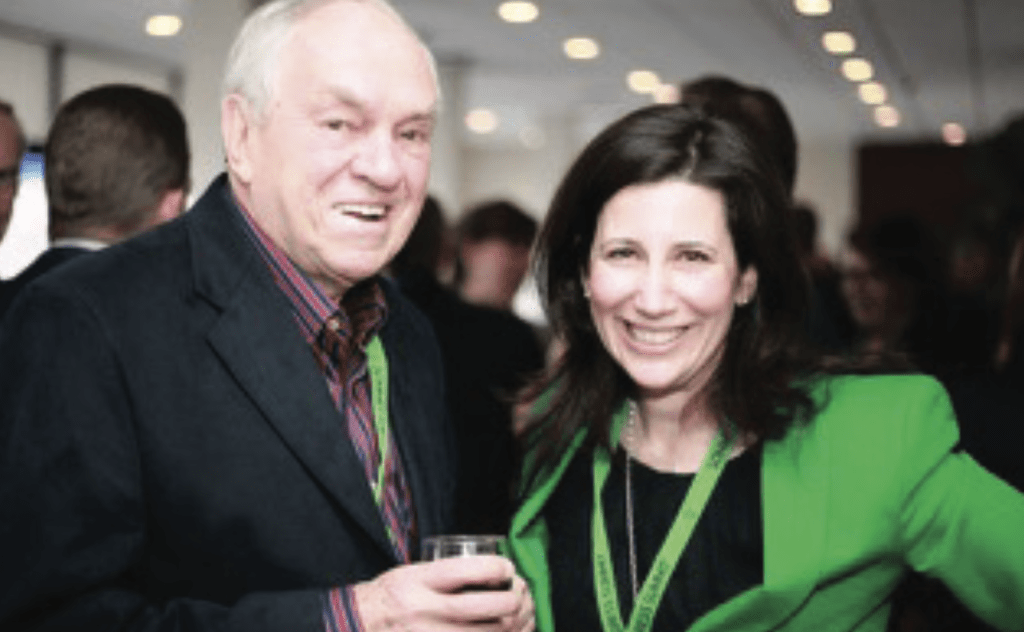

If the NDP was to win back political space for a social democratic narrative, it needed its alternative story tellers. The Broadbent Institute was built on a vision of an organization with three pillars: research, communication and media profile, plus training. It was an idea whose time had come. In just four months after the gathering at the Blakeney memorial the Institute was launched in Ottawa in September 2011. In less than a year their founding Executive Director, Kathleen Monk – a former journalist and senior Layton advisor as communications director – had raised several million dollars and developed their workplan and initial projects..

Through his work as vice president of Socialist International with European social democrats including Willy Brandt and Olaf Palme, Broadbent saw the power of the European parties’ supporting institutions. Broadbent had learned how effective they were in recruitment, training and impacting national political debate. His vision of the Broadbent Institute was to deliver the same tools to Canadian social democracy. He cites with pride the impact that an Institute conference in Vancouver, on the eve of John Horgan’s election victory, had in injecting new ideas and political focus into the campaign. He recalled that the victorious premier had called him soon after to say thank you.

Ed Broadbent is a somewhat improbable giant of Canadian social democracy. The son of a General Motors auto worker father and homemaker mother in Oshawa, Ontario, he grew up in an entirely apolitical household. He graduated first in class in political philosophy at University of Toronto before becoming a professor at York. He now admits with a wry chuckle that his youthful arrogance made him dismissive of the NDP campus activists of the early 1960s. He didn’t want any part of it — he was devoted to the study of political theory, not engaged in political agitation. He became active based on his involvement with Hungarian refugees arriving on campus. In the 1962 federal election he was roped into working for a rather naive Welsh NDP candidate whose idea of election tactics was bellowing at rich Rosedale residents through a megaphone that he was the “Socialist Candidate in this Election.” An inauspicious introduction to the local campaign tactics of New Democrats.

The Oshawa NDP knew they had a potential star in Broadbent and urged him to run. He demurred in 1965. In 1968 he defeated a popular Red Tory, Mike Starr, by 15 votes, the closest race in that campaign. He immediately took to Ottawa, Parliament and being an MP. The transition from a progressive academic who disdained partisan jousting was complete. But he never forgot the importance of being “about something more important” than smacking your opponents. It was a time of deeply emotional Canadian nationalism. Young progressives were sick of Vietnam and increasing American dominance of the Canadian economy. That was the fuel that ignited the internal revolt known as the Waffle (“If I have to waffle, I’d rather waffle to the left…”). It quickly became a serious challenge to the party leadership, especially that of David Lewis as federal leader and his son Stephen as the Ontario party leader. Broadbent was sympathetic to the demands for a more ambitious social democratic agenda and the group’s efforts to push the party to more progressive stances on the economy and social justice. He was an early supporter of some of their ideas, to the consternation of some friends and colleagues.

By the time of the party’s 1971 convention, which confirmed David Lewis’s leadership, he had re-considered. Increasingly concerned about the divisions the Waffle was openly generating, with his friend, the eminent Canadian political philosopher Charles Taylor, he crafted a compromise resolution for the convention on the economic and social agenda for the party. The “composite” resolution passed overwhelmingly. The Waffle’s rise was blocked. Only months after the convention the Waffle began to fade. Broadbent and Taylor’s clever adoption of much of the Waffle’s language in their text was an effective roadblock. Reflecting half a century later Broadbent said, “You know, if they had dropped much of their fierce anti-American rhetoric, things might have gone differently. Chuck and I simply took many of their ideas and stripped out the most strident nationalism.” Improbably for an MP with barely three years’ experience, he threw his hat in the ring as a leadership candidate at the that same convention. He now calls it, “Probably the worst decision of my political life. David won and he deserved to. “

Broadbent served in the 1972-74 caucus, where the NDP wrestled Petro-Canada and the first campaign finance act out of the minority Liberal government, among a variety of other legislative victories. In 1975, he again ran for leader and this time won a large victory. It launched a chapter in the party’s history that was among the most successful, increasing seats and popular vote in almost every race until the Mulroney landslide nearly 10 years later. But it was the famous free trade election of 1988 that broke his heart and ended his leadership. It was not the rejection of the party’s strong opposition to the FTA, however, that he found so crushing. It was the rejection by Quebec voters. He had lavished dozens of visits and hundreds of hours on Quebec and Quebec issues and the party had devoted unprecedented millions of dollars. Not a single Quebec seat was won.

It takes enormous stamina and determination to lead a Canadian political party. The distances and hours on the road seem endless, the disappointments regular, a snarky media and a restless caucus a given. It is a rollercoaster life that often seems to have more downs than ups. Broadbent managed it with minimal complaint. His wife Lucille protected his children and his private time ferociously. Any staffer who attempted to steal any of the few private hours did not do it twice.

Broadbent dominated his caucus but with velvet gloves. He devoted hours listening to dissidents, slowly easing them back into harmony. He rarely used his authority for punishment. He was not a leader known to use fear as a behaviour modification tool or retaliation as a deterrent. That put him in a special class less rare in the NDP perhaps than in parties whose more ambitious aspirants self-select based on the odds of actually governing: No-one has ever called Ed Broadbent ruthless. His relationship with Pierre Trudeau was professional but cool, whereas Broadbent and Brian Mulroney found an early respect for each other. He was, in Mulroney’s view, “One of those rare things, that you don’t often see – a gentleman, a true gentleman in politics. Of course, we took hard shots as each other, but Ed never made it personal.” Following Broadbent’s decision to retire from the leadership, Mulroney reached out and offered him a role as CEO of the International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development (shorthanded as Rights & Democracy). He and Lucille moved to Montreal to run the centre, spending several very happy years there.

Rick Smith succeeded Monk as head of the Broadbent Institute, running it for most of its first decade. Quizzed about its astonishingly swift success, Smith says, “Without Ed, it would have been impossible.” That success in walking the sometimes painfully narrow path between independence and loyalty to Canadian social democracy and the NDP was not inevitable. Smith, a longtime green activist used to managing often quarrelsome struggles within the environmental activism realm, brought his experience and skills, walking the same tightrope, to the Institute. He used two techniques many times. The first was to invite skeptical outsiders to listen to speakers and panelists deliberately chosen for their boundary-stretching views, signaling an openness and tolerance for dissent not often displayed by political parties.

When there was a sharp division on a policy question, Smith would stage debates, allowing partisans from each side to slug it out publicly. Using his environmental networks, he brought hundreds of skeptical young activists to the Institute. From its training arm, many of them graduated to become party staffers and candidates. Working with Press Progress, their media division, many others became professional political communicators.

During the pandemic, Broadbent began to think about retiring as chairman of the institute, but he had one last project in mind: to give Canadian social democracy a deep and well-researched policy depth wrapped in a permanent set of values, as a guide to the future. With a small team, he began to draft what became the succinct “Broadbent Principles for Canadian Social Democracy” (inset link).

Few political parties in the western democracies have created such a tight guide to their raison d’etre. It opens with the simple but eloquent declaration: “We believe in building a Canada that is just and equitable. In this, egalitarian social democratic values serve as our guide.” It then enumerates six core values:

• Furthering economic and social rights in addition to political rights

• Creating a green economy that leaves nobody behind

• Understanding the transformative potential of electing social democratic governments responsive to robust social movements

• Strengthening workplace democracy including the right to a trade union and the fundamental role of the labour movement

• Dismantling structural systems of oppression

• Fully implementing the rights and title of Indigenous peoples and supporting their goal of achieving self-governance

As a contemporary progressive political declaration, it does not merely repeat a commitment to a strong public sector and an equally strong labour movement, but acknowledges the centrality of the fight for Indigenous, racial and gender rights. As a nudge to often-too insular partisans, it also heralds the “creativity and power of social movements.” The Broadbent Principles represent a summing up of the convictions and struggles of a life devoted to fighting for social justice.

Rick Smith left as executive director early in 2021, and Broadbent stepped down as chair ahead of the 10th anniversary of the Institute, later that year. He handed the baton to Brian Topp, an early backer of the Institute. Jennifer Hassum, a person described by Kathleen Monk as “Probably one of the best communications professionals and political organizers in the country,” is now the executive director.

In the 60 years since its founding in 1961, the history of the New Democratic Party has been one of occasional highs and many more crushing lows. Several times, the NDP came close to the fate of other third parties — the Progressives, Social Credit, the Reform Party — either being swallowed or simply fading away. The Greens today sit on the edge of a similar abyss. Each moment of genuine crisis — the Waffle, the constitutional crisis, and the party’s near-extinction in the 1990s — had one thing in common; the essential role played by Ed Broadbent.

He put his career on the line in the first two, and dragged himself back from retirement to reverse the third. It is not an exaggeration to say that the party might not have survived its Waffle divisions, its Charter civil war, or pulled off its 21st-century revival, if Broadbent had not played a key role in each. His healing power as a deeply compassionate political leader helped pull the party back from the brink.

It was Ed Broadbent’s strategic epiphany that the party could soar with a new leader with skills and authenticity similar to his own. His endorsement helped push a relatively unknown Toronto city councillor, Jack Layton, to victory. Broadbent rejects the suggestion that his career had such an existential impact. For those of us who were next to him for many of these fraught chapters, it has always been perfectly clear that, without Ed Broadbent, the NDP might not have survived. Not just the party but the country has been made better by his presence.

Contributing Writer Robin V. Sears, now an independent communications consultant in Ottawa, was national director of the New Democratic Party of Canada during the Broadbent years.