Economic Inequality, COVID-19 and the Butterfly Effect

Lisa Van Dusen/For The Hill Times

October 14, 2020

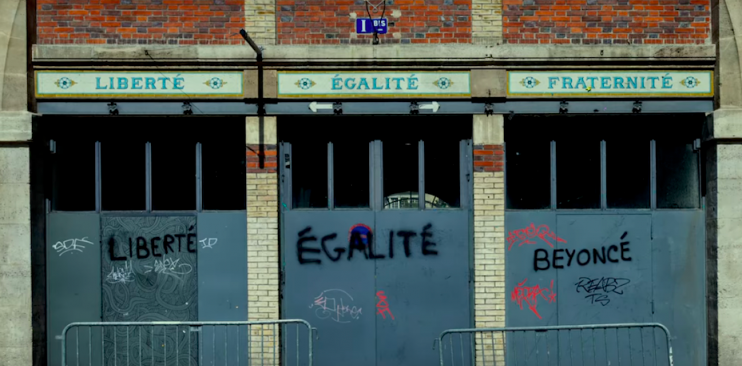

Back in 2013, when Beyoncé was Drunk in Love, Justin Bieber was breaking up with his pet monkey, and Donald Trump was still tweeting about Barack Obama’s birthplace, a literary phenomenon was born. The book Capital in the Twenty-First Century by French economist Thomas Piketty was published in the original French in August of that year.

By May 2014, the book’s English translation was a No. 1 New York Times bestseller and rising economic inequality had risen in the public discourse. “Gini coefficient” went from the national income inequality measure that peppers the chat at IMF/World Bank annual meetings, like the ones unfolding virtually this week, to something Bieber might name his next monkey.

This year, economic inequality is rising in more ways than on Google Trends (from 34 worldwide on Aug. 8 to 100 Oct. 10), as the necessary restrictions imposed to fight COVID-19 have hit struggling middle class, working poor, and poor citizens like a force-multiplying gut punch. As you may have heard, the graphic illustration of this is the inferior diagonal stroke of the letter K.

The K-shaped recovery isn’t just an alphabetic portrait of any bifurcated economy. Because of the context of this particular K, it captures the degree to which a pre-existing digital divide has been exacerbated by a pandemic that puts lower-paying, off-line jobs and the lives of the people who do them in greater peril. That lower leg of the K is the free-fall of human beings who are now experiencing acute vulnerability based on race, skills, education, access to health care, food security, and other determinants amplified by COVID.

Because of Canada’s social safety net—especially universal health care—emergency expenditures by the federal government, and our relative efficiency in containing the virus, it has seen less divergent trajectories. In September, 378,000 jobs were created—three quarters of the way to pre-COVID employment but gains still dependent on the whims of a virus and the race for a vaccine. The unprecedented factor in this recovery effort as opposed to 2009—domestically and internationally—is the exponential, inhibiting, and exploitable power of uncertainty.

In other words the deficit spending the IMF has urged to mitigate what managing director Kristalina Georgieva refers to as “scarring”—the long-term drop in productivity generated by lost skills, health, and hope—should factor in the future shock that loomed before the lockdown; the 40 per cent of jobs in the old economy expected to be lost to technology in the next decade.

Globally, the inequality impact of the lockdown is clear. In its “Poverty and Shared Prosperity Report 2020: Reversals of Fortune,” the World Bank last week estimated that between 88 and 115 million additional people will be pushed into extreme poverty in 2020. “To reverse this serious setback,” World Bank Group president David Malpass said, “countries will need to prepare for a different economy post-COVID, by allowing capital, labour, skills, and innovation to move into new businesses and sectors.”

In other words, the deficit spending the IMF has urged to mitigate what managing director Kristalina Georgieva refers to as “scarring”—the long-term drop in productivity generated by lost skills, health, and hope—should factor in the future shock that loomed before the lockdown; the 40 per cent of jobs in the old economy expected to be lost to technology in the next decade. Otherwise, the confluence of maladaptation, plummeting public revenues, and chronic pandemic deficits could create a debt trap with consequences beyond socioeconomics. Among other prospects, China—as the emboldened beneficiary of the catastrophic butterfly effect of a Wuhan bat—will presumably use its rapid recovery from the pandemic and relative economic heft to further leverage anti-democracy outcomes, including through the IMF’s New Arrangements to Borrow bilateral funding mechanism.

Meanwhile, Piketty’s new book, Capital and Ideology, isn’t the blockbuster follow-up it might be were its title Capital and Hypercorruption, since ideology is beside the point of most wicked problems these days. But the documentary Capital in the Twenty-First Century is on Netflix, and well worth catching while you can.

Lisa Van Dusen is associate editor of Policy Magazine and a columnist for The Hill Times. She was Washington bureau chief for Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News, and an editor at AP in New York and UPI in Washington.