Down Goes Loonie (Season 23, Episode 72)

Douglas Porter

October 27, 2023

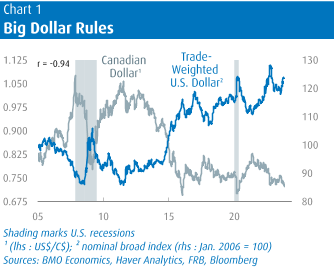

The loonie has never met a crisis it didn’t want to join. That’s not to say that the Canadian dollar is in crisis. At barely 72 cents (or $1.387/US$), it’s a long way from its all-time low of just under 62 cents in early 2002. And, it’s holding its own against currencies not named the U.S. dollar. But that is to say that this year’s bond market turmoil and geopolitical ruptures have sent the loonie skidding to its lowest ebb since the depths of the pandemic, when many (ahem!) were expecting it to strengthen in 2023.

One clear side effect of the remorseless rise in long-term Treasury yields—the pain trade of recent months—has been a broader rebound in the U.S. dollar itself, a secondary pain trade which has of course skewered almost all other currencies. In turn, this has complicated the inflation battle in economies with tight linkages with the U.S.—and few rank higher than Canada on that score.

Bank of Canada Governor Macklem was asked directly at this week’s post-decision press conference about how policy should respond to the lagging loonie. Without wanting to pile on the currency’s descent after holding rates steady, the Governor carefully responded that a weak currency implies that interest rates need to do more of the work than would otherwise be the case. In other words, ‘we certainly can’t cut any time soon, and we have to keep talking tough about possible further hikes, because a weak currency is making our job harder’.

The bar for another rate hike is very high indeed, with the Governor essentially also saying that inflation would have to exceed its forecast. And its forecast is surprisingly meaty. The Bank expects inflation to average 3% next year (versus 3.9% this year), the very high end of its tolerance zone, and well clear of the consensus of 2.6%. It’s even leap-frogged our normal spot as the inflation hawks (we have 2.8% next year).

The point is that it’s going to take a very nasty surprise on CPI to pull the Bank off the sidelines. Sadly, nasty surprises have been all too common in recent years, so no one is fully closing the door on the need for more tightening. But, one small pleasant surprise on the inflation front has been that the run-up in oil prices since the summer has quite simply not translated into pain at the pumps. Gasoline prices are now down about 10% from year-ago levels, and are headed for a monthly drop of more than 7% in October alone. This should provide some serious respite for the next CPI report, which could see headline inflation drop back to around 3%. In a nutshell, we continue to believe the Bank is done raising rates for this cycle.

Yet, we also believe that the Fed is done, with the market now almost universally expecting a second consecutive hold at next week’s FOMC meeting. And while there are some lingering odds that the Fed may go one more time later on—perhaps a nod to the dot plot’s aspiration—most are now looking ahead to rate relief by the second half of 2024. That’s a very similar picture to the outlook for the Bank of Canada, so current central bank expectations can’t fully explain the loonie’s latest lunge lower.

One weight on the currency, and/or a lift for the U.S. dollar, has been the extreme separation in relative growth performances in recent quarters. Normally, there tends to be little daylight between GDP growth rates in North America, with Canada’s outlook so closely tied to the fate of its neighbour. (And we don’t mean Greenland… or Russia.) But the playbook was cast aside in Q3, as the U.S. economy charged ahead at a 4.9% annual rate, while Canada likely struggled to stay in the plus column.

Next week’s August GDP release will include a flash estimate for Q3, and we suspect it will print just 0.1% (or about 0.3% annualized). In the 30 years before COVID, there were only two quarters when U.S. growth exceeded Canada by such a margin. One of those quarters was during SARS in 2003, and the other was in 2015 when oil prices collapsed—i.e., extremely negative events for Canada specifically. While the Canadian economy was dealing with some stuff during Q3 (a short B.C. port strike, and another wave of wildfires), those can’t come close to explaining the wide growth differential. Moreover, it’s not like this was a one-quarter fluke. Over the past four quarters, the U.S. economy has expanded 2.9%, while our Q3 estimate would leave Canadian GDP up a meagre 0.6% y/y. A yearly gap of more than 2 percentage points is at the upper bound of what’s normal in the past 60 years.

What makes the U.S./Canada growth gap even more eye-opening/disturbing is the much faster population growth in the latter. In fact, in per capita terms, U.S. GDP has seen more than 2% growth in the past year, while Canada’s has declined by more than 2%, a staggering divergence. What explains this yawning gap? We can point to at least two short-term factors at work:

- The household sector is under more strain from rate hikes in Canada. Saddled with much higher debt levels, and with a faster turnover in rates, consumers are pulling in their horns. U.S. real consumer spending popped at a 4% annual rate in Q3, and is up a sturdy 2.4% y/y. In contrast, Canadian real spending likely only nudged up in Q3, and is up a modest 1.6% y/y—again, well below even population growth, and spending is one component that would most be flattered by increasing numbers. Moreover, the much bigger weight of housing in Canada’s GDP means that the negative contribution from falling residential construction is a heavier drag.

- U.S. fiscal policy has been much more forceful. In the past week alone, both countries reported their FY23 budget balance, and the contrast was stark. The U.S. deficit widened to $1.7 trillion, or more than 6% of GDP, and it would have been closer to $2 trillion without some helpful special factors. Meantime, in a bit of a ‘man bites dog’ story, Ottawa’s deficit landed below forecast at $35.3 billion last fiscal year, or 1.3% of GDP (down from 3.6% the prior year).

The fiscal fuel was a big reason why the consensus (and we) completely underestimated U.S. growth this year. We will repeat a favourite factoid: The U.S. economy will grow faster on average this year (at about 2.4%) than it did last year (at 1.9%)—not a single major economic forecaster was calling for that at the start of 2023, when instead the conventional wisdom was looking for at least a mild downturn this year. In complete contrast, and much more conventionally, Canada’s growth rate decelerated to an average of just over 1% this year from 3.4% in 2022, as one would largely expect amid a ferocious tightening of monetary policy.

We would assert that a mild tightening in fiscal policy was the much more prudent and recommended path to take in the past year, when the number one economic concern was dealing with the fastest inflation in four decades. Instead, the U.S. fiscal largesse has forced the Fed to go a lot further than even it anticipated late last year (as we have previously noted, not a single dot plotter called for rates this high a year ago, not even Bullard). It has also juiced U.S. growth, and by extension, the U.S. dollar—to the inflation pain of all others, including Canada.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.