(Don’t) Take It to the Limit

Douglas Porter

May 12, 2023

In a generally quiet week for the economy, when even the U.S. CPI was largely as expected and caused few ripples, markets began casting a warier eye on the debt ceiling tussle. Bloomberg recently called it the crisis no one wants to talk about, but there is now no choice, with the ceiling about to bite within weeks. The Washington-manufactured crisis is being most clearly expressed in a run-up in short-term T-bill yields and CDS spreads. One-month bills are now yielding almost 50 bps more than their 3-month counterparts, an exceptionally wide and unusual spread, reflecting the intensifying near-term risk to government paper. (A less polite commentator may well ask: “With this crew, do you really think holding three-month paper is any better?” But I digress.)

The debt ceiling is sometimes cited as a driver on down days for stocks, but the S&P 500 was roughly flat this week as equity investors seem to not really believe what’s unfolding on Capitol Hill. Longer-dated Treasury yields also were roughly unchanged amid the brewing crisis, although ongoing regional bank woes likely played a bigger role in holding down yields. It’s always passing strange that the very instrument whose creditworthiness is in doubt in a debt-ceiling impasse—Treasuries—benefits from flight to safety/liquidity during said impasse. Similarly, the U.S. dollar actually strengthened this week amid the dual banking stress/debt ceiling concerns.

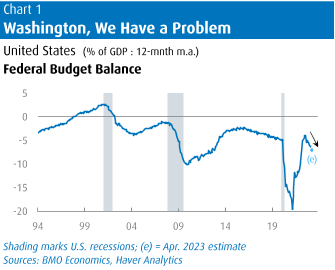

This week’s Focus Feature digs into all the details on the debt ceiling and the implications of even a brief default. One addition we’ll make to the robust commentary is that, even aside from the clear and present debate, the U.S. fiscal situation is truly concerning. In the past 12 months, Washington has run a $1.94 trillion budget deficit, or more than 7% of GDP and up from $1.20 trillion a year ago. It’s true that roughly $300 billion of the shortfall reflects the one-off of student debt relief, but even excluding that, the gap is $1.6 trillion and 6% of GDP. Just prior to the pandemic, the deficit was running at roughly $1 trillion, or just under 5% of GDP. So, it’s a long-standing, bipartisan issue, which is getting worse. To put it in perspective, if Ottawa was running a budget deficit of 6% of GDP, that points to a C$170 billion shortfall, and some commentators would be apoplectic.

Notably, the U.S. deficit is actually smaller as a share of GDP than during the intense debt-ceiling squabble in the summer of 2011 (when it was 8% of GDP). But there are three key differences. First, government finances were on the road to recovery at that point after the crushing hit of the Great Recession. This time, they are deteriorating again after an initial recovery from COVID (Chart 1). Strike one. Second, the economy was much weaker in 2011 with the jobless rate at 9% that summer, so a large fiscal shortfall was somewhat reasonable. This time, we are beyond full employment, with the jobless rate of 3.4% the lowest since the Korean War, so there is zero justification for such a large deficit. Strike two. Third, inflation was not a major issue in 2011, with core CPI running right around 2% then, so there wasn’t a macro necessity of running a tighter fiscal policy. This time, even with an okay April result, core CPI is still chugging along at a 5.5% y/y clip, or about 3 ppts too hot for comfort. So, there’s plenty of macro justification for a tighter fiscal policy. Strike three.

The bottom line here is the U.S. is running a large and re-expanding deficit, at a time when the economy is running flat-out, and inflation pressures remain strong. That makes no sense from an economic policy standpoint. Thus, as much as we decry the tactics, one can readily sympathize with the goals of those attempting to use the ceiling as a tool to enforce some fiscal tightening. It’s quite apparent that the regular budget process is not doing the job. Having said that, clearly a default is the worst possible outcome, like ingesting poison to try to fix a wound. When it comes to handling poison, Congressional leaders would do well to consider the immortal final words (as rumour has it) of Socrates: “I drank what?”

The bottom line here is the U.S. is running a large and re-expanding deficit, at a time when the economy is running flat-out, and inflation pressures remain strong. That makes no sense from an economic policy standpoint. Thus, as much as we decry the tactics, one can readily sympathize with the goals of those attempting to use the ceiling as a tool to enforce some fiscal tightening. It’s quite apparent that the regular budget process is not doing the job. Having said that, clearly a default is the worst possible outcome, like ingesting poison to try to fix a wound. When it comes to handling poison, Congressional leaders would do well to consider the immortal final words (as rumour has it) of Socrates: “I drank what?”

There were no major Canadian economic releases or Bank of Canada events in an exceptionally light week. However, a couple of normally tertiary releases are worth a mention. First, consumer and business insolvencies took a big step up in March, with the former rising 28% both from the prior month and from a year ago. Business insolvencies rose 37% y/y to their highest in more than a decade. There are a few ‘yes, buts’ here, as insolvencies are rising from extremely low levels during the pandemic, when a combination of government support, forbearance, and very low borrowing costs provided enormous relief. The second caveat is that the insolvency data are not seasonally adjusted, and March is normally a heavy month on this front. Still, they are well up from a year ago, and there is little doubt that with the support factors removed, the underlying trend in insolvencies is on the rise.

The second release is related, with the Bank of Canada’s quarterly Senior Loan Officer Survey (for Q1). In the wake of the U.S. regional bank stress, this survey was more important than usual for signs of spillover. Loan officers did indeed report a significant tightening in household lending conditions, especially for mortgages, where things tightened the most in the six years of the survey. While mostly on the price side, even non-price metrics tightened notably. Similarly, non-price conditions on business lending firmed, but certainly not to an extraordinary extent. The survey on business loans has a much longer 24-year history, and the latest net-tightening reading of +11.3 (where zero is neutral) is well below prior stress periods, and not in the same league as the record +75.8 reported in 2009Q1. In other words, much like insolvency tallies, things are tightening after a remarkable period of favourable conditions, but there are not serious signs of stress—yet.

Where there is some serious stress in Canada is on the Leafs’ Cup chances. While I fully expect that they’ll still be playing for many, many more weeks, one does have to hedge one’s bets that this could be the last chance to comment. After a very successful season and round 1, it would really be a shame to fumble it away to a team from the hockey haven of South Florida (with all due respect, of course). But we’ll just point out that the Buds and their high-powered (and high-paid) offence have now scored precisely 2 goals in each of the past six games. It’s tough to win consistently at that pace, absent a world-class defence and goalie. World-class is not a description that leaps to mind, but happy to be proven wrong.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.