Dispatch from China: An Exercise in Chinese Public Diplomacy

China’s famed Terracotta Army/Aaron Zhu

China’s famed Terracotta Army/Aaron Zhu

By Colin Robertson

June 26, 2024

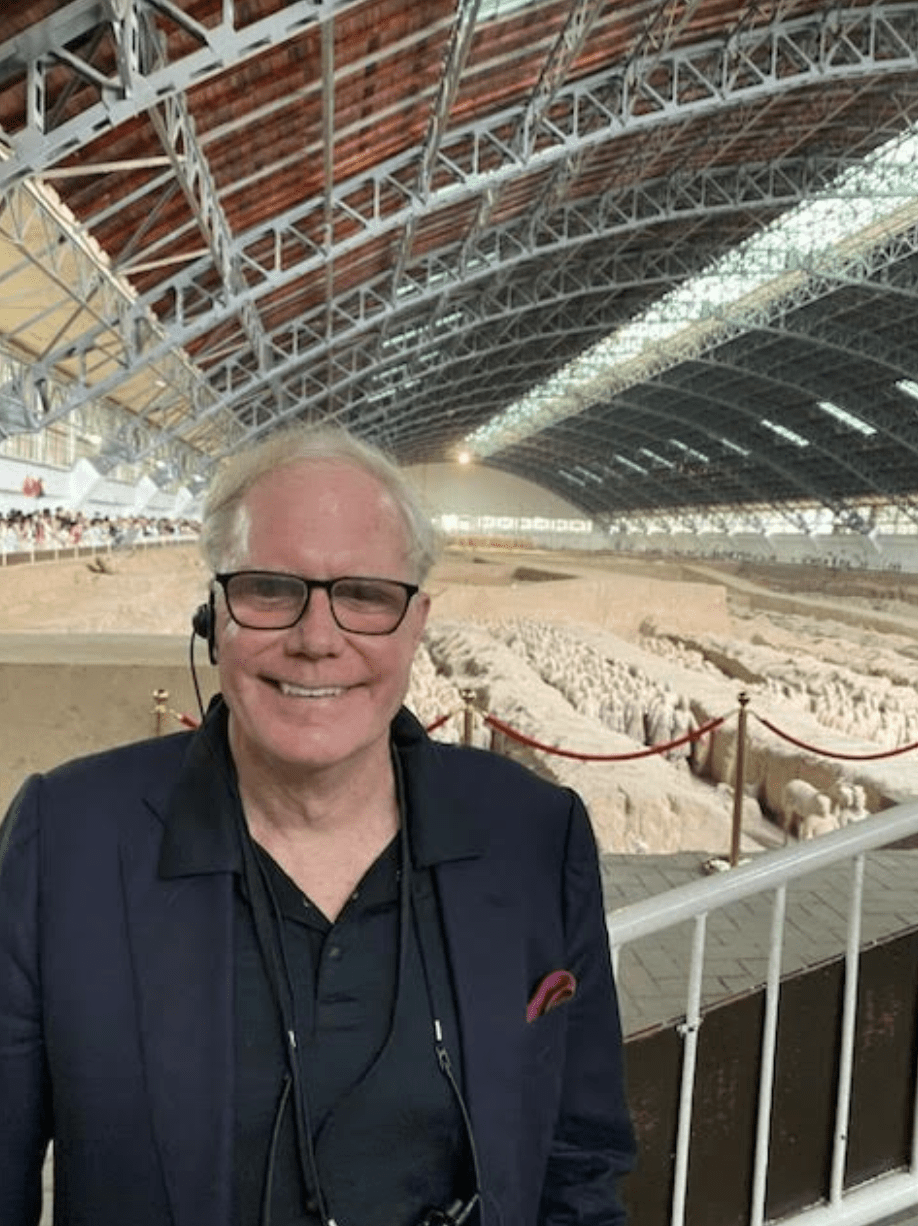

Entombed 2,200 years ago to protect Qin Shi Huang, China’s first emperor, the terracotta warriors are one of the ancient world’s wonders. After uniting the Middle Kingdom, Qin consolidated his power creating a single Chinese state under a single ruler. Unity and uniformity were his guiding principles. Some things in China don’t change.

It was my first time back in China since September 2019, when I’d attended the People’s Liberation Army security conference. This time, I was invited to participate in the annual Wanshou Dialogue hosted by the Chinese People’s Association on Peace and Security. Excursions to Xian and Yan’an were part of this exercise in Chinese public diplomacy.

Rediscovered by a farmer tilling his land in 1974 (we were assured he is now rich), what strikes you about the warriors is not just their numbers – more than 8000, not including chariots and horses – but the veneration they now enjoy with the Chinese. In a secular state these are as close as you get to holy relics. Qin’s tomb will never be opened, in respect to the original Supreme Leader – and they are holding off on future excavation until they can find some way of preserving the ancient colours on the warriors that, for now, fade with exposure to light.

The author with the Terracotta Army, outside Xi’an

With its greenhouses spreading as far as I could see, our visit to the Yangling Agriculture Park, on the outskirts of Xian, was a reminder that feeding 1.4 billion Chinese is a paramount economic and social priority — one rendered more urgent by climate change. Between 2000 and 2020, the country’s food self-sufficiency ratio decreased from 93.6 percent to 65.8 percent.

A high-speed train took us next to Yan’an to see the Yangjialing Revolutionary site, where Mao Zedong and his comrades lived in caves during parts of the Japanese occupation and Civil War. To reinforce our appreciation, we did our own ‘long march’ in a five-hour tour through Yan’an’s Revolutionary Memorial Hall, where we were instructed in the historical catechism of the Communist Party of China.

To complete the experience, we bused to Lingjiahe village to see where Xi Jinping endured almost six years during the Cultural Revolution after the purge of his father. According to Xi’s biography, he also lived in a cave, built wells and joined the CPC, becoming local party secretary. It is possibly the experience of sleeping six on top of a furnace that Xi recalls when he tells young Chinese to “actively seek hardship”.

China’s new generation of shoppers in Beijing/AP

China’s new generation of shoppers in Beijing/AP

Despite reports that the economy is flagging, Beijing, Xian and Yan’an were bustling. When I first visited Beijing in the spring of 1988, its citizens still dressed like Mao, rode bicycles and inhaled coal-fueled smog. Today all is changed: the latest fashions with haute couture boutiques doing a roaring business, with BMWs, Mercedes and Lexuses filling the roadways although they now contend with the Chinese-made Honqis, Dongfengs and the ever-popular BYD stable of affordable EVs. One could describe it as ‘capitalism with Chinese characteristics’.

Post-COVID, I spotted about as many masks as I would in Canada: few and mostly worn by the elderly. The longstanding national addiction to cigarettes has been replaced by cellphone use. We passed a series of unfinished apartment buildings in Xian – a reminder of the property over-build. When I remarked on the disciplined traffic throughout, a colleague asked had I not noticed the blinking flashes at almost every corner – facial recognition cameras keep track of everyone’s movements, also ensuring motorists’ compliance.

Established in 1985 the Chinese People’s Association on Peace and Disarmament is a Communist Party of China creation with its own hotel and conference facilities.

The multi-nation Wanshou Dialogue is their signature event that this year took as its theme: “the overstretching of global security”. We were 35 foreigners, most from Asia, Africa and the Middle East – outreach to the global south was very much the goal of our hosts.

I’d wondered if my fellow delegates would be mostly ‘fellow travellers’ but they proved to be independent-minded. They included a former Austrian defence minister, a former South Korean security advisor, a former Indonesian cabinet secretary, a former Singaporean foreign minister and a former UN under-secretary general. We came from think tanks and universities with most having previously served in government or the military.

Those from the ‘global majority’ were at pains to underline that they are not a united bloc. They have their own interests and priorities. What came through clearly in our discussions is that they do not want to take sides in the Sino-US confrontations.

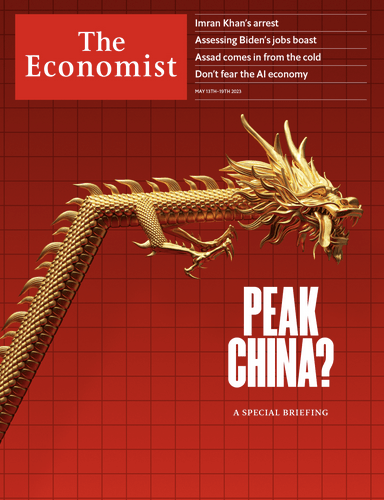

Our hosts’ main message was that the ‘Peak China’ narrative that has circulated in the West (which itself peaked with the Economist cover package of May 13, 2023, above) is false. It may not be double-digit, but China’s GDP is still growing at 5 per cent. As to Chinese technological prowess, they pointed to that day’s spacecraft landing on the dark side of the moon.

Frustrated over what they see as the ‘securitization’ of trade and investment through protectionism and sanctions, Chinese officials who spoke with us say that their climate mitigation measures, especially in manufacturing efficient and affordable electric vehicles and solar panels, are unfairly suffering from tariffs designed to keep them out of US and EU markets.

While the Chinese expressed no preference for Biden or Trump, they are preparing for a return of Trump.

Participants agreed that nations are overstretching military security in response to heightened geopolitical tensions. I said that rearmament in the West is the natural response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and to Chinese rearmament and aggressive behaviour towards its neighbours in the Indo-Pacific.

I argued for investing in human security and addressing migration (the post-war refugee conventions were not designed for economic or climate migrants) as well as addressing inequality and the growing divide between rich and poor – both within states and between states. I said the West had learned the hard way through Iraq and Afghanistan that we cannot export democracy but that when it is threatened, as in Ukraine, we must support and stand with democracy.

There was a general consensus that co-existence between different states and systems has worked in the past and while we are engaged in technological competition we must collaborate and cooperate in finding solutions to shared problems, especially climate, migration, counterterrorism and countering weapons of mass destruction.

To ignore China or try to contain it won’t work nor will it serve our interests. We need to engage and to co-exist.

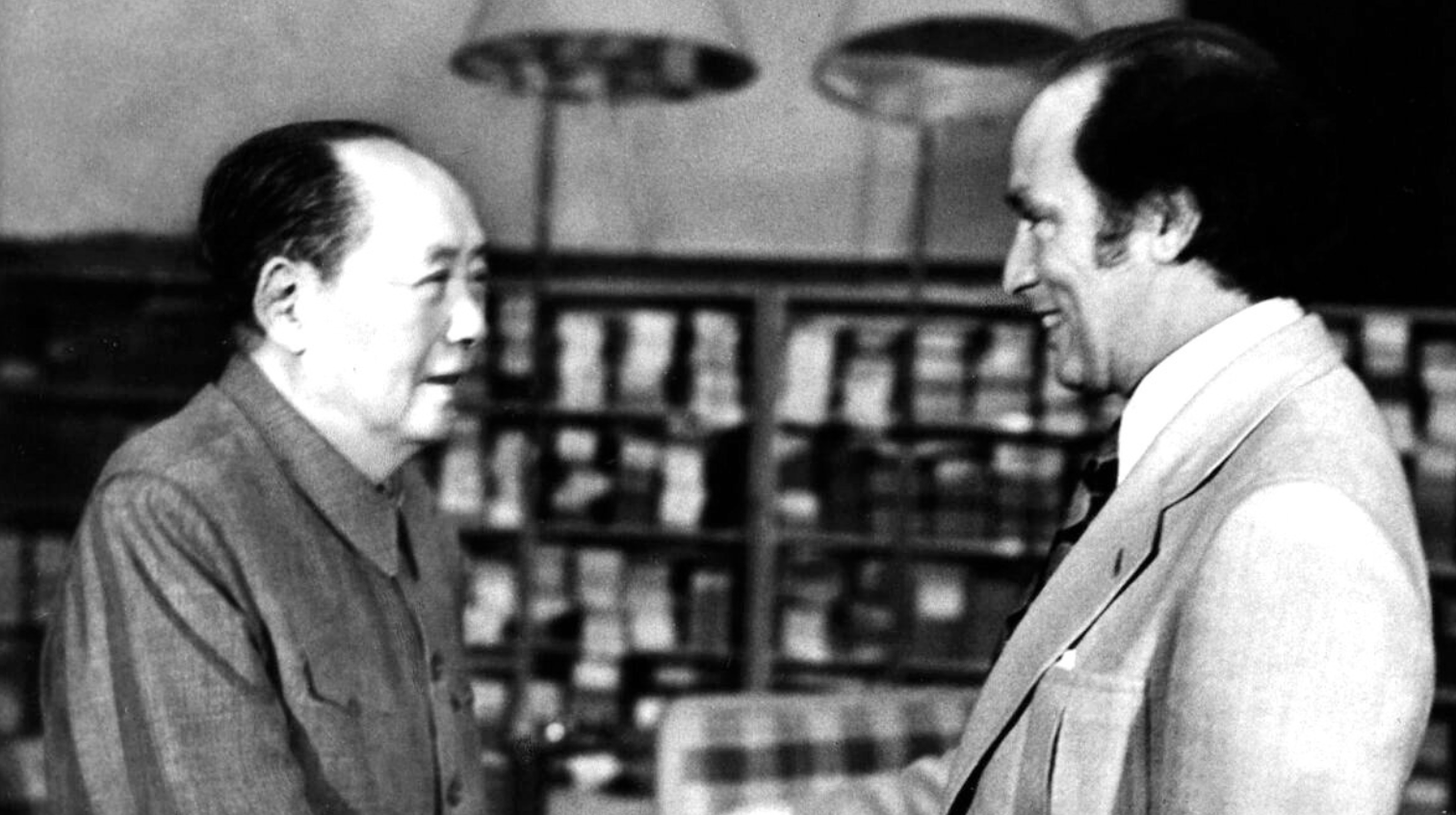

My trip reminded me that the West has lost the advantage that Kissinger and Nixon engineered in the 1970s when they individually cultivated Mao’s China and Brezhnev’s Soviet Union, effectively separating the pact between the two communist powers – a situation that lasted until this century. Now we face a Sino-Russian alliance that is working for both partners, even if it’s not ‘endless friendship’.

Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau with Mao Zedong in Beijing in 1973/CBC image

As for the future of Canada-China relations, we need to recognize some critical realities:

First, we are seen by China as a much lower priority than we were in 1970, when Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau was the first Western leader to recognize Communist China, or even 2016, the year of his son’s first official visit to China. We are treated as such. We must develop a deep understanding of our China relationship and what that means for the US-led system that has given prosperity and security. Despite the influx of Chinese migrants, China expertise in our universities is diminishing and knowledge of China within governments and business remains thin.

Second, we need to change our mindset and expectations and recognize that, with China, everything is a matter for negotiation. We always need to keep in mind two lists: what they want and what we want. Turning a blind eye to CPC-inspired intellectual property theft (notably Nortel and probably Blackberry) and foreign interference in our democracy doesn’t work. CSIS director Dick Fadden’s warning in 2010 was dismissed as scare-mongering. We need to define and then call out foreign interference and send the perpetrators packing immediately but quietly (meaning no prime ministerial statements in the House of Commons).

Third, the Chinese understand power and strength. They also understand weakness. For them our passive-aggressive behaviour is weakness. They will take all they can get until they are called out. We normally avoid linking issues. But, with China, we should embrace linkage, especially with trade, security, tourism and climate, because this is how the Chinese do business.

Fourth, we still have not got our narrative on China right. This begins with research and understanding and the new GAC Centre for China Policy Research and Coherence has work to do. Foreign Minister Marc Garneau said Canada would take an ‘eyes wide open’ approach based on the four ‘Cs’ to co-exist, cooperate, compete and challenge China. These 2021 talking points need policy enunciation of what that means, nuances largely absent in the Indo-Pacific strategy. Then, we need to get our story straight, making it consistent, clear and compelling and retelling it again and again via ministers and officials. It would help to have broad parliamentary agreement.

Fifth, we can help create a better level of communication between the United States and China, the diplomatic imperative of our time.

We must establish our own bona fides for quiet diplomacy, rather than strident virtue-signalling. This begins with re-establishing with China what the Australians call ‘normalization’ or ‘stabilization’ in people-to-people ties and trade and investment.

During the Cold War, we made a useful contribution to ‘incident management’ to prevent misreading from becoming catastrophe through measures like Pierre Trudeau’s ‘peace initiative’ and ongoing disarmament diplomacy. We need to resurrect quiet diplomacy and resume our role as a helpful fixer and useful nation.

Sixth, we need to resurrect our capacity as the foremost interpreter of the United States to a world increasingly confused and anxious about the American direction, especially if Trump is president. We also need to bring our diplomatic network’s perspective to a Washington that always welcomes our informed intelligence. Doing so advances our own interests. American actions like the Biden tariffs on Chinese EVs, will oblige commensurate action on our part to preserve our preferred access to the US, as confirmed by Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland on June 24, with the announcement of a 30-day “consultation” on potential tariffs on Chinese EVs. As we were reminded with Trump, trade is economic security, which is national security. We need early warning and then analysis to understand and then advocate. Another reason for investing more in our diplomacy, defence and development.

A final reflection: some of my fellow delegates – a Nigerian who enjoyed an International Development Research Centre (IDRC) fellowship and a Kenyan general who took peacekeeping training – told me separately that Canada possesses ‘real soft power’ and strategic ‘moral force’. Why don’t you apply it, they asked? Why indeed …

Policy Contributing Writer Colin Robertson, a former career diplomat, is a fellow and host of the Global Exchange podcast with the Canadian Global Affairs Institute in Ottawa.