Diplomacy A-Go-Go: Trudeau Hits the Road for a Whirl of Summits

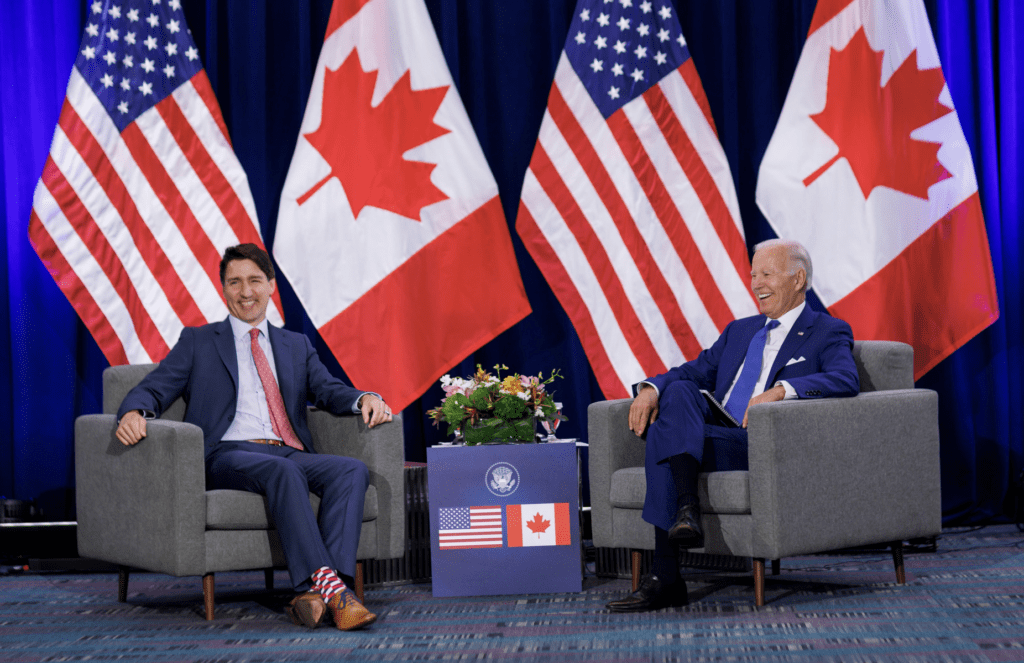

White House photo

White House photo

Colin Robertson

June 22, 2022

In this month of renewed face-to-face summitry – the Americas, World Trade Organization (WTO), the Commonwealth (CHOGM), G7, and NATO – we are getting a sense of a shifting world order in which the United States is no longer transcendent and in which our democratic verities no longer prevail. There is a role for Canada but only if we are up for it.

For now, managing global order is going to be complicated and confused. We will have to experiment, adjust and adapt to ever-changing circumstances and new threats. Facing institutions no longer fit for purpose, it means more ad-hockery, including coalitions of the like-minded to get things done.

What is certain is that the democracies will need to devote more attention to diplomacy and, in the case of Canada, more investments in defence and development. Decisions on vital issues like trade, climate and health will be at best incremental. We will have to pay special attention to funding – pledges must be delivered – and to follow-through.

Citizens, especially in the democracies, are seized of social and racial inequalities, skeptical of governments and business, and hostile to traditional elites. This is particularly true of a United States still reeling with political polarization and the virulent sedition that culminated on January 6, 2021. But if we learned anything during the Trump years it is that without American leadership, the democracies flounder.

All this takes place against the grim backdrop of a sharpening divide between autocracies and democracies. There is Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Vladimir Putin’s territorial aspirations of an empire modeled after Peter the Great. There is something between a mutual decoupling and contempt between the US and China, most recently expressed in the competing speeches of US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and Chinese Defence Minister Wei Fenghe at the June 10-12 Shangri-la Dialogue.

As voting patterns at the UN illustrate, most nations don’t like what Russia is doing, but when it comes to sanctions, outside of the G7 and European Union and a handful in the Indo-Pacific – Australia, New Zealand, Korea, Taiwan and Singapore – most are sitting on the fence. Ambassador Bob Rae described this well in a recent piece for Policy magazine:

“Recent tactics adopted by Russia, China and other interests aiming to degrade democracy and replace the rules-based world order with one more amenable to their interests and less accountable to humanity did not exist and could not have been foreseen amid the debris of Hitler’s rampage,” Canada’s Ambassador to the UN writes. “They have been enabled by the deception, corruption, coercion and propaganda-amplifying innovations of new technology. The threat of nuclear conflict represents a more overt form of leverage meant to evoke a power hierarchy beyond moral authority.”

If this plate of problems were not enough, there is continuing climate change, the pandemic is still with us and now we face rocketing inflation and economic stagnation, the bane of democracies.

The Americas summit in Los Angeles (June 6-10) was supposed to be about migration, climate and economic development. Instead, the media focus, before and throughout the meeting, was on Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez-Obrador’s boycott over who was not invited – the dictators of Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela. It should have been obvious. Leaders, meeting in 2001 in Quebec City, agreed to the the Inter-American Democratic Charter declaring that any break with democratic order is an “insurmountable obstacle in the participation of that state’s government in the Summit of the Americas process.” But aside from President Biden and Prime Minister Trudeau, there was no collective voice in Los Angeles speaking out for democracy. The Inter-American action plan announced at Biden’s Democracy summit (December 2021) got only passing mention.

The contretemps did underline that the Americas are relatively fragmented and that the US no longer holds sway. China has surpassed the United States as South America’s largest trading partner. Beijing has free trade agreements in place with Chile, Costa Rica, and Peru, and 20 Latin American countries have so far signed on to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to build their infrastructure although, as Asians and Africans will tell them, they need to be wary about the ultimate costs.

In Los Angeles, 20 countries, including Canada, signed a declaration to help and protect “all migrants, refugees, asylum-seekers and stateless persons, regardless of their migratory status.” Canada pledged $27 million promising to take more refugees by 2028, including those from French-speaking nations such as Haiti, and to recruit more temporary agricultural workers.

The Los Angeles summit also netted initiatives on cities, health and resilience, and a US partnership on climate with the Caribbean. President Joe Biden also announced a US plan for economic partnership in the Americas but it’s a long way from the free trade area of the Americas from “Canada to Chile” envisaged by President Bill Clinton as part of the post-Cold War architecture. Clinton hosted the first summit in Miami in 1994. The intent was to eventually bring the 35 nations of the Americas into a hemispheric league of democracies. It’s an idea whose time is not yet come.

As with the rest of the world, the democratic ideal in Latin America has slipped in recent years. With conservative governments seen to have failed to deal with inequities, a pink tide has now put leftist leaders into office, most notably in Canada’s Pacific Alliance partners– Mexico, Chile, Peru and now Colombia.

With its economies accounting for more than two-fifths of global GDP, when the G7 acts collectively, its decisions make a difference.

With the World Bank estimating that trade accounts for 61 percent of Canadian GDP, the recently concluded World Trade Organization ministerial meeting (June 12-17), the first in five years, matters. To the surprise of most observers, the 164 member states reached agreement on WTO reform, vaccine production and fishing subsidies. The challenge, as always, will be in meeting and, inevitably, enforcing those obligations. There is still no agreement on dispute settlement, the issue on which Canada is leading reform efforts.

More than most nations, trade generates Canada’s prosperity. It is why we have always been active participants in sustaining an open, rules-based trading system, whether multilaterally at the WTO, through plurilateral regional agreements such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and Canada-EU Comprehensive Economic Trade Agreement (CETA) and our recently renegotiated North American agreement (CUSMA).

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is participating in the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (June 23-25) in Kigali, Rwanda. There is controversy over the next Secretary General as well as the Rwandan regime’s human rights record – Freedom House ranks Rwanda “not free” – and over British Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s plan to send migrants to Kigali for processing.

Although only 35 of the 54 leaders will be there, Trudeau can profitably spend his time taking the pulse of his fellow leaders, especially the Africans, as to their energy and food situations given the turmoil created by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. It will be useful intelligence for the next stops in his journey: Schloss Elmau for the G7 and then Madrid for the NATO summit.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the emerging Commonwealth was described by Louis St-Laurent as a pillar of Canadian foreign policy, complementing the relationships with the US, UN and NATO. While Pierre Trudeau was originally disdainful, he soon realized it was his entrée into the leadership of the developing nations and that within the forum of the now 54 members of the Commonwealth – including 19 African, 12 Caribbean and eight Asian nations – Canada could play a pivotal role as both “helpful fixer” and “bridge”, a role that Brian Mulroney and Jean Chrétien also realized. If the Commonwealth is less relevant today, it is still a place where Canada stands outside of the shadow of the United States and, as the senior dominion, without the colonial baggage of the United Kingdom.

The G7 (June 25-28) is hosted this year by the new German chancellor, Olaf Scholz, and the leaders will meet in Schloss Elmau, high in the Bavarian Alps. It’s picturesque but also security-wise, which is why the Germans chose to use it in 2015, when they last hosted the G7. The host sets the agenda and “Progress towards an equitable world” is how theGermans sum up their objectives around the economy, climate and health. But the focus will be on security, including addressing the energy shortages and the looming global hunger crisis caused by Russia’s blockade of Ukrainian wheat.

Shoring up international support in the now-explicit rising threat of autocracy is the priority, recognizing that the dynamic has not been one of mutually engaged bilateral conflict but of a trend toward existing democracies being degraded and replaced by autocracies through a range of factors that reward leaders and regimes for corruptly betraying the interests of their own citizens.

The Germans have invited the leaders of Senegal, South Africa, India, Indonesia and Argentina to join the meeting and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky will join by video link. As Chancellor Scholz put it, the purpose is to “strengthen the cohesion of the democracies” recognizing that “major, powerful democracies of the future are in Asia, Africa and the American South and will be our partners.”

With its economies accounting for more than two-fifths of global GDP, when the G7 acts collectively, its decisions make a difference. Meeting first in 1975 to deal with the economic fallout from the energy shocks of the early 70s, its summits are now the culmination of a yearlong process of meetings, including ministerial tracks: foreign, finance, development, digital, energy, trade, health and environment. Then there are the now- formalized engagement groups: Business7, Civil7, ThinkThank7, Labour7, Science7, Women7 and Youth7.

Comparing the G7 to an iceberg is apt: if the annual leaders’ summit is the tip and most visible piece of the G7, this coordinated process involving ministers and officials lies mostly beneath the surface of public attention but is vitally important. More people probably work on the draft of the final communiqué than will read it but the process of getting there is what really matters. The G7 final communiqué always looks like a smorgasbord but it reflects the G7’s role and the many challenges it must address.

If the G7 is the management board for the democracies, NATO has represented their collective defence since 1949. Canada played a role in its creation – Article II on economic cooperation was a Canadian initiative – and Lester Pearson was offered the job of being its first Secretary General.

The NATO summit (June 28-30) in Madrid will be one of its most consequential as it adapts “to a changing world and keeps its one billion people safe.” Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg has put three questions to NATO’s 30 members and nine global partnernations:

- How has Russia’s brutal and unprovoked invasion of Ukraine and the new security reality in Europe affected NATO’s approach to deterrence and defence?

- What is the Alliance doing to address other challenges, like China’s growing influence and assertiveness or the security consequences of climate change?

- What will be included in NATO’s next Strategic Concept, the blueprint for the Alliance’s future adaptation to a more competitive world where authoritarian powers try to push back against the rules-based international order?

There is also the expected invitation to Sweden and Finland. Traditionally neutral, both now want to join NATO. NATO acts through consensus and Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan, an often disruptive member, is demanding the Swedes change their support of what he calls Kurdish terrorism.

Inevitably, members will be reminded of their 2014 pledge to spend 2 percent of GDP on defence by 2024. Canada spent approximately 1.4 percent of GDP on the military in 2021, putting it in the bottom third of the Alliance. The Parliamentary Budget Office estimates Canada will reach 1.59 percent by 2026-27. For Canada to reach the 2 percent of GDP benchmark, the government would need to spend between $13 and $18 billion more per year over the next five years.

Most of the NATO allies say they will reach the 2024 target. Following the Russian invasion, German Chancellor Scholz reversed decades of German foreign policy by providing weapons to Ukraine and putting billions more into defence. As we are learning in Ukraine, in the final analysis it’s all about will and the hard power to back it up.

The divides between the leading autocracies – China and Russia – and the developed democracies, under the necessary but domestically distracted leadership of the United States, on issues of human rights, trade and international norms, are increasing.

In what promises to be a prolonged period of tension, diplomacy will matter more than ever if we are to avoid further acts of aggression similar to Vladimir Putin’s illegal invasion of Ukraine.

We need to take care with too-clever phrases like “arc of autocracy”. The Russia-China entente is less an alliance than an interest-based relationship between strategically autonomous powers. Both have declared their desire to replace the existing world order. China wants stability while it is working assiduously to adjust the liberal rules-based norms to its own design. Russia is a disruptive power that thrives on disorder. Russia is also very much the junior partner. Frictions between the two powers are inevitable.

Much of the world, including the most populous developing democracies such as India, Brazil, Indonesia, South Africa, Nigeria, and Pakistan, are sitting on the fence. As a Singaporean observed at the Shangri-la Dialogue, Asians do not want to align. They wish that both sides would dial down their insults. They are fearful that “red lines” only escalate tensions.

Canada sits firmly in the democratic camp, but we need to recognize that the world order is once again shifting under pressures, new and old. Reforms are necessary. There is room for niche diplomacy and acting in our traditional role as both helpful fixer and bridge-builder.

We must be vocal in defending and advancing our democratic values. It also means significant and sustained new investment in Canadian defence, diplomacy and development. But are we up for it? And do we have the necessary cross-party political will for what will be a sustained effort, with inevitable setbacks and disappointments, over the life of several governments? If not, be prepared for a grim world.

Contributing Writer Colin Robertson is a former career foreign service officer who served in America and Asia. He is now Senior Fellow and Adviser to the Canadian Global Affairs Institute in Ottawa.