Debt, Growth and the ‘Madman Theory of Economic Policy’: This Year at the IMF

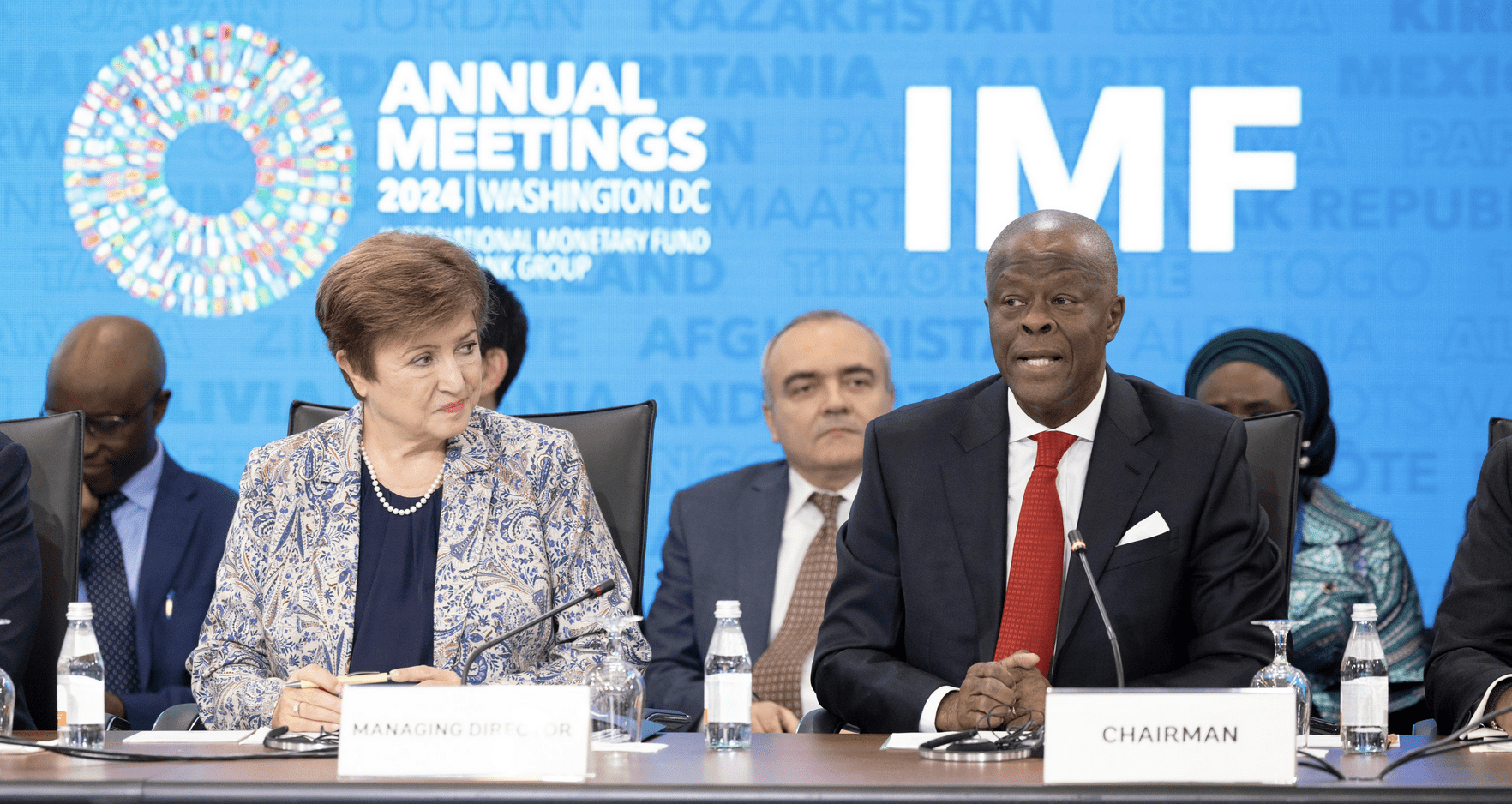

IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva and Africa Caucus Chair Wale Edun on October 22, 2024/IMF

IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva and Africa Caucus Chair Wale Edun on October 22, 2024/IMF

By Kevin Lynch and Paul Deegan

October 23, 2024

As the International Monetary Fund approaches its 80th birthday next year, it is worth recalling the prescient words of President Roosevelt’s message to Congress proposing the Bretton Woods Agreements: “The point in history at which we stand is full of promise and of danger. The world will either move towards unity and widely shared prosperity or it will move apart into necessarily competing economic blocs.”

Picking up on this wicked choice in her curtain raiser to the 2024 IMF-World Bank Annual Meetings in Washington, IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva, observed: “We live in a mistrustful, fragmented world where national security has risen to the top of the list of policy concerns for many countries. This has happened before — but never in a time of such high economic co-dependence.” She then goes on to challenge the Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors from around the world attending the meetings to “Not take the global tensions as given, but rather resolve to work to lower the geopolitical temperature and attend to the tasks that can only be tackled together”, citing in particular international trade, climate change and AI.

Contradictions, which abound in today’s global environment, have been frequent topics of discussion in Washington. The Fed appears to have engineered a soft landing for the U.S. economy — an outcome few thought likely only a year ago — and yet a majority of Americans think their economy is in bad shape and consumer confidence is weak. The Russian invasion of Ukraine drags on, support for Ukraine is softening in the U.S. and Germany, the fighting in the Middle East is widening, and yet stock markets are booming.

Public debt is at record levels in many countries — the U.S. deficit is close to 7% of GDP and public debt is roughly 100% of American output — and yet, neither U.S. presidential candidate has committed to fiscal restraint, quite the opposite in fact, and populist addictions to deficits and debt are present in many OECD countries including Canada. American consumers have been battered by high inflation, and yet polling support for Trump remains strong despite the fact that his main economic proposal —massive increases in tariffs — would significantly drive up prices on imported consumer goods. Such contradictions point to the scale and nature of risks to the global outlook.

The main risk to not only the U.S. outlook but the global economy was not on any agenda for the IMF meetings but was prominent in every conversation. To provide analytical context for the Trump economic risk (they left it to others to comment on the threat he poses to democracy and the Bretton Woods ideals), the Peterson Institute for International Economics, an influential Washington think tank, published a scathing critique of Trump’s proposed economic policies in the lead up to the IMF meetings. It argues that Trump was “weaponizing uncertainty” given the scale and scope of his proposals: mass deportations of over 1.3 million people, massive tariffs of 60% on goods from China and 10-20+% on goods from elsewhere, large tax cuts and spending that would expand already high deficits and debt, and curtailing Fed independence.

Their conclusion is that, if implemented, they would lead to U.S labour shortages, widespread supply shortages, inflation spikes, lower growth, higher U.S. government debt and bond yields and a reduced role for the U.S. currency in global commerce. Some even described Trump’s policy package as the “madman theory of economic policy” — so extreme that it is designed to get maximum concessions from foreign governments on trade, from businesses on moving operations to the U.S., from Congress on his pet policies, and from the Fed to take a softer line on inflation. Whatever the Trump plan, “his strategy would impose uncertainty throughout the U.S. economy” according to the Peterson study, not to mention its impacts beyond America’s borders.

The main risk to not only the U.S. outlook but the global economy was not on any agenda for the IMF meetings but was prominent in every conversation.

The good news in the IMF update is that, after the worst surge in inflation in a generation, and an initial much too-slow response by monetary authorities, high interest rates have done their job — inflation is in retreat in most economies and interest rates are coming down without hard landings. But, while inflation targets are within reach, prices remain high and they are squeezing pocketbooks, particularly for lower income households, and hurting consumer confidence.

The debt news is not so good. Pandemic era debt exploded, as governments acted to support COVID impacted economies and societies, but it has continued to grow as governments have been loath to cut spending and embrace restraint despite the rapid rebound of economies. The IMF argues that the combination of loose fiscal policy, less-than-stellar economic growth and weak productivity creates the risk of a worrisome debt dynamic unless governments shift their priorities to sustained fiscal consolidation. Simply put, the IMF thinks governments should spend less, subsidize fewer distorting activities and raise revenues to rein in deficits and debt. And it calls out the world’s two largest economies, whose debt dynamics are not stabilized.

The headline from the IMF’s updated World Economic Outlook, where global growth is projected to average a tad over 3%, is that “growth is stable but underwhelming — brace for uncertain times”. The pleasant surprise is an upgrade to American growth — now 2.8% this year and 2.2% in 2025 — demonstrating the impressive resiliency of the U.S. economy despite high interest rates and its political dysfunction. European growth is certainly in the underwhelming category, growing less than 1% this year and last, and struggling to get much above 1% next year. The question mark is around China and its struggle to meet the government’s 5% growth target going forward given its property sector problems and overcapacity in manufacturing.

Plodding along is the best way to describe the Canadian outlook: growth is expected to be less than half that of the United States this year, at 1.3%, as indeed it was in 2023, before perking up in 2025 to 2.4%. Even this growth has been somewhat artificial, driven by a massive surge in temporary foreign workers and students. A better measure given this population shock is real GDP per capita, which tumbled last year by -1.5% and may fall even more this year depending on year end immigration numbers. By way of comparison, our neighbour to the south increased its GDP per capita by almost 2 1/2% in both years.

Looking ahead, the IMF advises governments to engineer a “triple policy pivot” — cutting interest rates as inflation and inflation expectations become anchored with inflation targets again; shifting to sustained fiscal consolidation and rebuilding prudential fiscal buffers; and, instituting structural reforms to revive growth and drive improvements in living standards. Canada has considerable work to do on two thirds of the IMF’s policy pivot.

One challenge, as the IMF notes, is that “structural reform enthusiasm” has waned since the global financial crisis due to a rise in populism, a decline in trust and a lack of leadership. Structural reforms are tough because they are essentially about modifying acquired rights and economic rents. So, success, according to some fascinating IMF research, requires mobilizing a coalition for change, setting out credible estimates of the costs of maintaining the status quo, creating viable transition programs for those affected and engaging in sustained, two-way, public communications — sounds a lot like how Canada moved forward on free trade in the 1980s and deficit elimination in the 1990s.

Kevin Lynch was Clerk of the Privy Council and vice chair of BMO Financial Group.

Paul Deegan is CEO of Deegan Public Strategies and was a public affairs executive at BMO and CN.