Crafting a New Canadian Foreign Policy: Strategic Sovereignty in a ‘Leaderless’ World

As American leadership wavers, Canada must achieve ‘strategic sovereignty’, writes former NATO Ambassador Kerry Buck/Shutterstock

As American leadership wavers, Canada must achieve ‘strategic sovereignty’, writes former NATO Ambassador Kerry Buck/Shutterstock

By Kerry Buck

February 11, 2025

Right now, almost all of Canada’s foreign policy discussion, strategy and collective brainpower is focused on Donald Trump’s second presidency. This is smart – there is a high risk that President Trump will cause significant damage to, or at least disruption of, Canada’s economy, our security and the global structure we have relied on since the end of the Second World War.

So, it is clear that our diplomacy and foreign policy have to adapt.

But defining Canada’s foreign policy has been difficult for us even at the best of times. We haven’t had a foreign policy review since 2005. Part of the challenge has been the historical tension in our foreign policy between a desire to carve out Canada’s own space on the global stage and the need to align with the U.S. Today, the job of defining our foreign policy has become even more difficult, primarily because America’s global leadership role is changing in ways that are difficult to predict.

While Canada needs to adapt its foreign policy to be ready for a changed world, the problem is that the eventual shape of that changed world is far from clear. What Canada needs to do differently will depend on what we’re trying to manage. Many say President Trump is an isolationist. I’m not convinced. He’s a disruptor but he also likes ‘winning’, Thus, his promises to end the Ukraine war in 24 hours, or his odd threats to annex Greenland, Panama and Canada. So, it is not at all clear what US foreign policy will look like for the next four years.

If Trump means what he’s been saying in the early days of his presidency, then his foreign policy will be marked by an extreme form of U.S. exceptionalism and the use of American power in an unrestrained or unilateral way. If his foreign policy ends up being more about U.S. isolationism, then this would cause the US to turn away from its traditional global leadership role. Either way, Canada has to adjust its strategic, tactical and conceptual approach to Canadian foreign policy.

This requirement to adapt is not just a reaction to an American President seemingly bent on being even more disruptive and unpredictable than he was in his first term. Regardless of who is in the White House, the U.S. willingness (or power) to act as a global leader has been weakening over the past decade or more, and it will continue to weaken. This is because the global landscape has fundamentally changed since the international system we rely on today was first established.

The exercise of global leadership has become increasingly difficult: with a five-fold growth in the number of states; many states turning away from multilateral solutions and toward nationalism and protectionism; economic and political power moving from West to East and North to South; states like China, India and Russia contesting the American role and others from the Global South choosing not to align with either the US or its competitors. The weakening of American global leadership predates Trump, it will likely be exacerbated by him, and it will outlast him.

If Trump means what he’s been saying in the early days of his presidency, then his foreign policy will be marked by an extreme form of U.S. exceptionalism and the use of American power in an unrestrained or unilateral way.

For many of the same reasons, some argue that the space today for Canadian influence is more constrained. While this is true, it does not mean that Canada cannot and should not set itself up to have a shaping role. The stark alternative is to focus inward and — depending on how the bilateral relationship with the U.S. unfolds — assume a subordinate role within “Fortress North America” or a more vulnerable one as “Island Canada”.

In a world with new centres of power, weakening international institutions and interconnected threats that cannot be addressed without cooperative solutions, Canada has no choice but to avoid overdependence on the U.S. in our foreign policy choices and develop greater strategic sovereignty. Above all, the aim should be to rebuild Canada’s strategic culture and confidence. Defining the national interests that drive our international policy priorities would give decision-makers a strategic framework to decide when we would part company with the U.S. and when we would align. This is what I mean by “strategic sovereignty”.

So, how do we achieve strategic sovereignty? I argue that Canadian international policy makers should ask three key questions:

First, as American global leadership wavers, what impact will this have on the relative importance of Canada’s global engagement when compared to our bilateral relationship with the U.S.? There is a longstanding thread running through Canada’s foreign policy — a dividing line between the public policy choices we see as necessary and those we see as optional. This walks back to our immense and longstanding reliance on the US as the anchor of our economy and continental security. While we see engagement with the US almost as domestic policy that is both existential and necessary, aside from the early post-WWII years, the rest of our foreign policy and defence engagement abroad has largely been seen as optional. If we are safe and prosperous in Fortress North America, then we can pay less attention to geopolitics.

This approach might have made eminent sense throughout some of our history but it is not tenable any more. The direct costs of events such as climate disasters, the Covid pandemic or the Russian war in Ukraine to Canada’s economic and security interests are undeniable. “Fortress North America” will no longer afford us the security or economic dividends it once did. As geographic distance is collapsing, Canada needs to start seeing international engagement not as optional but rather in Canada’s existential interest.

We will always be tied to the U.S. because of our geography, but Canada must consistently and consciously choose when it is in our national interest to diverge from aligning our international policy positions with the U.S. To do this, as I argue above, we need a clearer articulation of our national interests and the development of a more confident strategic culture. We also need to have the tools and expertise to engage internationally in a strategic way that responds to those national interests.

While the second Trump presidency has crystallized these urgencies, the problem is that we have significantly underinvested in our tools of international engagement — defence, development, trade and foreign policy. A quick survey of the budgets of our international departments over the past thirty years shows investments that have declined significantly in real terms — in development and foreign policy/trade — or that have failed significantly to keep pace with allies and heightened security risks — defence.

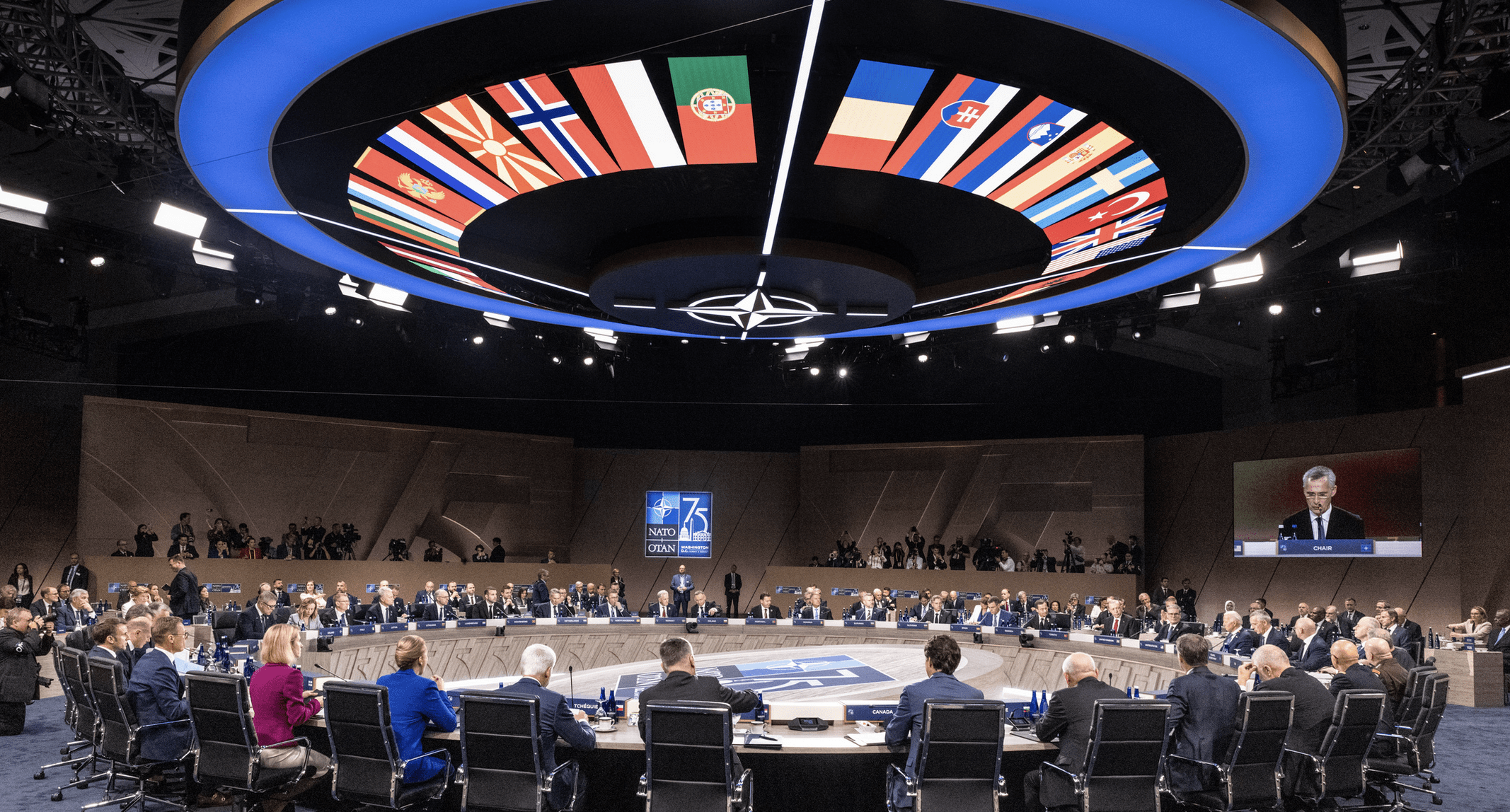

The NATO 75th anniversary meeting in Washington, July, 2024/NATO image

The NATO 75th anniversary meeting in Washington, July, 2024/NATO image

Second, how we should adapt our own global engagement to take into account a less-engaged U.S.? For middle powers such as Canada, bodies like NATO, the UN or the G7 act as force multipliers, enhancing leverage. We have used them effectively in the past to try to keep the U.S. engaged internationally, build cross-regional, issues-based alliances to support Canadian interests and initiatives, or to build new norms to temper extremes of state behaviour. Think of the landmines treaty, children’s rights, maternal and child health, human security, or the creation of NATO. On most of these issues, Canada took a conscious policy choice to promote an initiative that ran counter to, or pushed beyond, U.S. positions.

However, the role of the U.S. in the global architecture we’ve relied on since the end of the Second World War is now fraying and transforming in ways that will inevitably make it harder for Canada to navigate internationally. Again, this is not a development that has just surfaced with the second Trump Presidency. U.S. influence in multilateral bodies has been steadily shifting over the past few years, owing to a number of different push and pull factors. American leadership has been incrementally crowded out by competitors, notably China. Acutely aware that the UN is an ecosystem and that what you say in one forum will echo in other negotiations — China uses this to rewrite the rules, taking advantage of Western lack of coherence. And many more states are now occupying a ‘middle space’ at the U.N., “forum shopping” for the right alliances, depending on the issue and their interests and not automatically aligning with traditional Western or other negotiating blocs, so states wanting to exercise leadership have to work harder to build support.

The U.S. has also increasingly chosen to be less ‘multilateralist’ in its orientation. During his first term, President Trump repudiated alliances like NATO and withdrew the U.S. from the WHO and the Paris Agreement. President Biden also, albeit with a different tone, focused less on global bodies like the UN in favour of purpose-built US-led fora like the Democracy Summit or the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework. In sum, where the U.S. used to act as a multilateralist in a unipolar world, for more than the past decade it has been acting as a unilateralist in a multipolar world. And this is not about to change. It is highly likely that the approach to multilateralism under the second Trump term will continue to include a repudiation of American treaty commitments, condemnation of multilateral institutions and alliances, and a view of the liberal international order as being dominated by globalist elites.

This will have a profound impact on Canadian foreign policy, which has traditionally had multilateralism at its core. And yet turning away from multilateralism to focus inward or rely on our bilateral relationships to protect Canadian interests would inevitably result in a weakening of Canada’s global stature and leverage, in turn lessening our capacity to exercise influence bilaterally. A sounder strategic approach would be to maintain Canada’s focus on multilateralism, focusing on those issues that both correspond to Canada’s core interests and fill in gaps in international norms, some of which will have been created by the U.S. retreat.

Third, how have Canadian interests, assets and vulnerabilities changed as a result of the shift in the U.S. global leadership role and what should Canada’s international policy priorities be? Canada must be able to navigate a world where the gap is growing between, on the one hand, what Canada needs and on the other, what America wants or is willing to do: a world where the American security guarantee is less reliable; one where America is hostile to free trade while Canada is a trading nation; where America is alliance-skeptic while Canada relies on alliances and partnerships and where American democracy is destabilizing and polarizing while Canada relies on resilient democracy as a core Canadian value. In all of these areas, Canada is already more vulnerable. Our foreign and security policy priorities haven’t adapted.

Canadian decision-makers should take a strategic, structured approach to redefining our interests, vulnerabilities and assets. An international policy review should break down the barriers between international strategy and national security and be integrative, spanning trade, national security, defence, diplomacy, resilience and development. My own personal short list for Canada’s international priorities that would both respond to increased vulnerabilities and capitalize on Canadian strategic advantages would be:

- further diversifying our trade and investment partnerships, with an emphasis on Indo-Pacific and sectors where Canada has a comparative edge (eg. critical minerals, space, agri-food);

- concentrating our security and defence efforts on our continent and region, strengthening transatlantic collective defence and diversifying our defence relationships in areas of particular vulnerability like the Arctic;

- building security and societal resilience by tackling cyber security, democracy, foreign interference and disinformation; addressing climate change (including food security) and

- (re)building the international rules, organizations and guardrails that directly touch on our economic and security interests (like emerging technologies, nuclear non-proliferation, migration and human rights).

Ideally, the redefinition of our international priorities would involve an open, public debate to engage Canadians and redefine our national narrative on Canada’s global role. While Canada has traditionally been loath to write down its foreign policy, it has been even more averse to engaging in broad public conversations on international issues. But engaging Canadians makes sense now for a few reasons.

First, today’s international security environment is the worst it has been since the end of the Second World War and a public process would build Canadians’ security awareness. Second, a public process would inform and build legitimacy for a new direction in Canada’s international policy. Most importantly, at the same time as Canadian decision-makers will have to make significant commitments in defence and border security to manage the bilateral relationship with the U.S., public engagement will help build the case for why this is in Canada’s longer-term national interest and not just a response to President Trump.

Our default approach to international engagement has too often been to wait until the U.S. asks before we step up internationally. The aim should be for Canada to take a shaping role to build the open, stable international environment that meets our national interests. If Canada’s global role today might be described as a “middle power with small-power aspirations” the aim should be to align our level of ambition with Canada’s status as the worlds 9th largest economy, the 7th largest military power in NATO, and a member of the G7.

Policy contributor Kerry Buck, a career foreign service officer, was Canada’s Ambassador to NATO from 2015-2018. She is currently a Senior Fellow at the University of Ottawa and the Bill Graham Centre for Contemporary International History at Trinity College, University of Toronto.

This article is an updated version of one first published in the International Journal, Volume 79, Issue 3, and first presented at the Canada Program at Harvard University’s Weatherhead Center for International Affairs in spring 2024.