COVID, Politics and the Role of Leadership

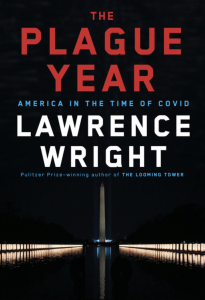

The Plague Year: America in the Time of Covid

By Lawrence Wright,

Alfred A. Knopf/2021

Reviewed by Graham Fraser

July 29, 2021

When Lawrence Wright was about six years old, he woke up one morning paralyzed from the waist down. It turned out not to be polio, which was raging in the early 1950s; it might have been Guillain-Barré syndrome; it might have been a severe allergic reaction. Whatever it was, he recovered, but it gave him a lifelong sensitivity, literally and figuratively, to disease. Last year, he published a novel about an imaginary pandemic; this year, he has published a non-fiction account of how the United States responded to the first year of COVID-19.

The Plague Year is his 13th book and, he suggests, perhaps his last. That poignant sense of sadness and mortality shades his account of the disastrous first year of the pandemic in the United States.

Wright is a New Yorker writer, and a glimpse of this book appeared in the magazine. It is marked by some of the characteristics of the publication: personal stories of researchers and medical experts interspersed by deeply researched information about pandemics in general and COVID in particular.

The outline of the story is familiar: Dr. Li Wenliang, an opthalmologist in Wuhan, China, who re-posted a colleague’s note about an atypical virus, was charged with rumour mongering and forced to sign a confession. He caught the virus, and died on February 6 — prompting mass mourning in China from those who had been shocked by his punishment.

In the United States, Wright introduces Dr. Barney Graham. His title is deputy director of the Vaccine Research Centre and chief of the Viral Pathogenesis Laboratory and Translational Science Core at the National Institutes of Health. His job is simpler than his title; as Wright put it, “He studies how viruses cause disease and designs vaccines to defeat them.”

The story, then, is twofold: scientific triumph in developing an effective vaccine, and, at the same time, political disaster in undermining public trust in science and delaying the introduction of an effective public health response.

Pandemics, Wright observes, “are disruptive, divisive, and always political. Science does not necessarily get the last word. Political leaders have to balance saving lives and saving the economy. Prejudice plays a role — so strikingly demonstrated with HIV — and the disparities on health outcomes prompt resentment and racial strife. Grief and fear generate irrational actions. There would be blame-shifting and bitter recriminations.”

For while Graham was developing what became the Moderna vaccine, Donald Trump had dismantled the White House team in charge of global health security, appointed so-called experts who favoured allowing the virus to spread, and consistently downplayed the risk that the pandemic represented. Trump’s team was divided and in conflict and when Trump was himself infected with the virus and then saved by frantic medical intervention, he wilfully drew the wrong message.

“As he was preparing to leave the hospital, he imagined hobbling out as if he were really frail, rather than hopped up on steroids, then yanking open his shirt to reveal a Superman jersey. In the event, he saved his drama for the moment he stood again on the Truman Balcony and defiantly ripped off his surgical mask,” Wright writes.

“‘Don’t be afraid of Covid,’ he tweeted. ‘Don’t let it dominate your life.’ Like Superman, he was feeling invulnerable. Unlike Superman, he wasn’t.”

Some of the figures in the book are familiar to anyone who has read a newspaper or turned on a television in the last year and a half, including Anthony Fauci and Deborah Birx. Despite their familiarity, Wright succeeds in presenting lesser-known aspects of their roles, such as the pilgrimage Birx made across the U.S. by car to persuade individual governors to impose stronger health measures.

Pandemics, Wright observes, “are disruptive, divisive, and always political. Science does not necessarily get the last word. Political leaders have to balance saving lives and saving the economy.

However, there was one person who figures in the Washington part of the account whom I had barely heard of: Matthew Pottinger. Pottinger was deputy national security adviser, but with an unusual background. At 25, fluent in Mandarin after a degree in Chinese studies, he moved to China as a reporter for Reuters and the Wall Street Journal. After seven years, he left journalism to join the Marines and, while in Afghanistan, wrote a paper on improving military intelligence with Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn. Flynn hired Pottinger to be his Asia director when Trump named him national security adviser. Flynn only survived in the role a few weeks; Pottinger lasted until the fateful day of January 6, 2021 when, following the insurrection — “the final superspreader event of the Trump presidency,” Wright observed, pointing out that dozens of cops would test positive — when, filled with a sense of rage at what had happened, he cleared out his office and quit.

But during the time he was there, he was a consistent if often overruled voice of sanity, armed with his understanding of China and helped by information from his brother Paul, an infectious disease doctor in Seattle.

Beyond the personal stories of key people in the Administration and health care professionals like Dr. Ebony Hilton, Wright is able to draw some sweeping conclusions. He identifies two key factors determining success in dealing with COVID: experience and leadership. Those countries that had been stricken by previous pandemics, like SARS, MERS, HIV/AIDS or Ebola did better than those that had not.

“The other quality was leadership,” he writes. “Nations and states that did well have been led by strong, compassionate, decisive leaders who speak candidly with their constituents.”

He is similarly analytical about the stumbles in the vaccine rollout in the U.S., which he describes as predictable. “There was no coherent national plan,” he writes, describing how there was vaccine scarcity, the states made up their own rules, and the virus changed, as all viruses do.

Wright ends the book with a comparison of American military readiness and pandemic unpreparedness. “We were ready to go to war with any other nation, but we were missing the fact that our own country was at war with itself, and that our weakened, broken society was easy prey for the contagion that was inevitably going to come.”

The final image in the book is of the 400 lamps that lined the reflecting pool in Washington the night before Joe Biden’s inauguration, each one representing one thousand Americans who had already died in the plague. As the author writes, more would come.

The ending, and its unspoken implication that a change of administration will mean the end of the plague, is faintly optimistic. But that optimism, no matter how subdued, now seems premature: the divisions Wright describes are deepening as the divide between the vaccinated and the unvaccinated widens and the Delta variant spikes.

Policy Contributing Writer Graham Fraser spent 19 years at The Globe and Mail, in Toronto, Quebec City, Ottawa and as Washington bureau chief from 1993-97. The author of several books, he served as Canada’s Commissioner of Official Languages from 2006-2016.