Could it Happen Here?

Despite occasional flare-ups of something possibly resembling a Canadian iteration of Trumpism, the divisive, bellicose brand of overt racism and xenophobia politicized by the populist American president has not yet jumped the border. Veteran Liberal strategist Patrick Gossage weighs the chances that populism will play into the 2019 campaign.

Patrick Gossage

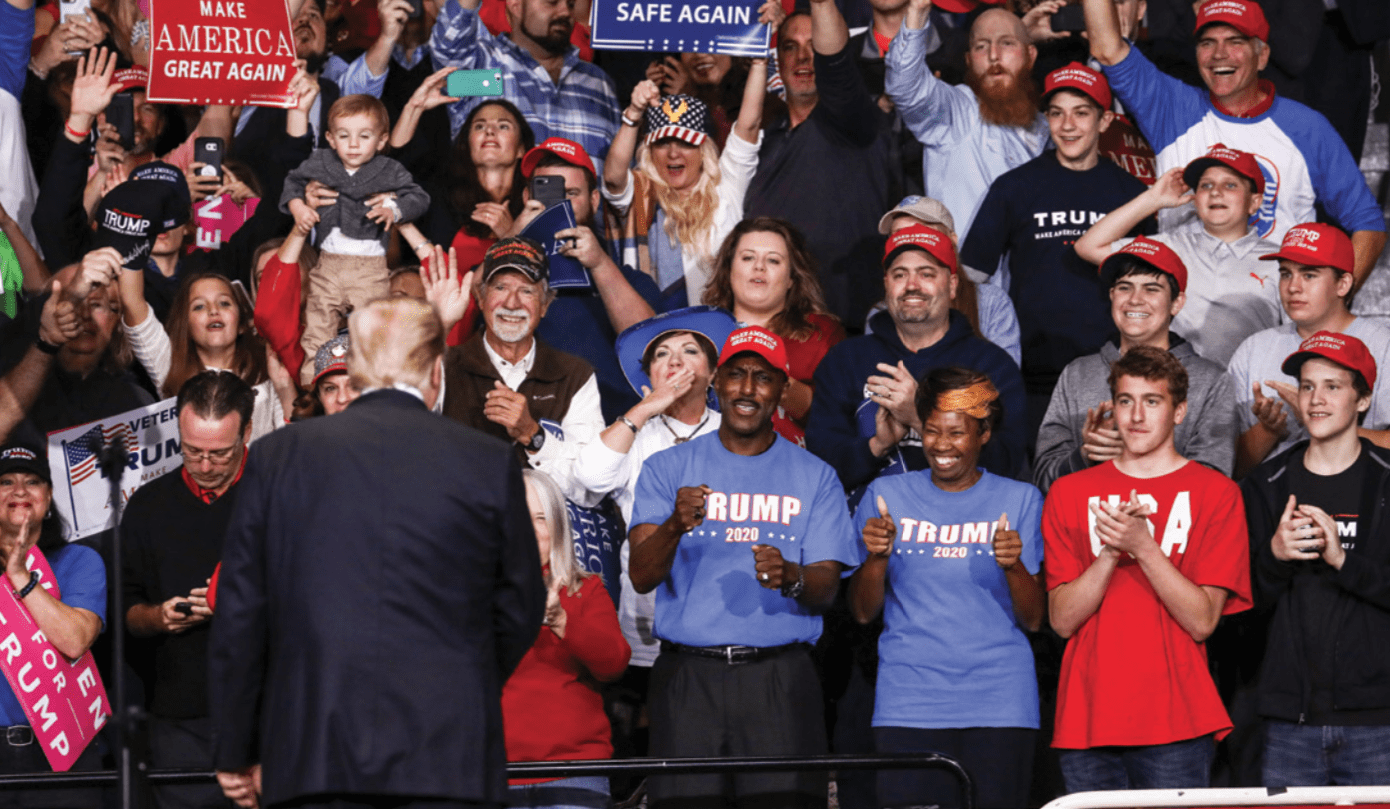

The last months of pre-election silliness have seen pundits and pollsters falling all over each other to try and show us that Canada is not immune to the anti-immigrant populism which has become so ugly south of the border, most recently with Donald Trump’s racist rants against four congresswomen of colour, telling them to “go back” where they came from.

This apparent jeopardy was accentuated when the federal government added two right-wing Canadian extremist groups, Blood and Honour and Combat 18, to its list of banned terrorist organizations. Add to this the Quebec government’s passage of Bill 21 banning public service employees from wearing religious symbols—including the Hijab, with its anti-Islamic discriminatory overtones.

Are we immune to populist trends gripping the Western world or not? And how will backroom strategists planning election messaging use media-stoked anxieties that we are on a slippery slope?

Frank Graves of Ekos Research fired off the most recent evidence of growing Canadian populism in late July. Graves argues that economic stagnation, the hyper concentration of wealth, and a brewing cultural backlash mean Canada’s political climate is ripe for populist forces to gain traction here. He posits the growth in the Conservatives’ attraction to the less educated as a potential reason for them to become more populist. There is also an exploitable widening gap between the attitudes that left- and right-leaning voters share towards issues such as immigration and climate change.

But his position has prompted other pollsters to disagree. Doug Anderson of Earnscliffe Strategy Group says his research has also shown conditions are there for “people to rally behind a populist candidate,” but none of the federal party leaders embody that mold. “There has to be a candidate who is seen as a champion for them, the antithesis of what they’re getting,” he said. “[It’s someone] who compellingly says, ‘I feel why your government serves the elite.’” He dismissed right wing People’s Party (PPC) head Maxime Bernier’s almost futile attempts to rally that minority.

Nevertheless, Liberal strategists have undoubtedly noted this with interest and may be tempted to position Justin Trudeau as the saviour of Canada from “creeping populism”.

There is good research that shows how divergent attitudes to immigration could play out in the election. An Environics poll last November gave strategists something to chew on. Just 22 per cent of Liberals and 24 per cent of New Democrats thought Canada takes in too many immigrants. But 52 per cent of Conservatives and 47 per cent of PPC supporters thought so. And 73 per cent of PPC voters and 70 per cent of Conservatives think too many immigrants are failing to adopt “Canadian values,” compared to 38 per cent of Liberals and 40 per cent of New Democrats.

Certainly, Liberals are accustomed to the frequent rants of Conservative immigration critic Michelle Rempel, who while careful not to sound anti-immigrant, forcefully disputes Liberals’ handling of the influx of “illegal” immigrants walking into Canada at the Quebec border. She likes to cite an Angus Reid poll from August 2018 showing 49 per cent of respondents felt there should be fewer immigrants allowed into Canada. That figure was 36 per cent in 2014.

This tendency for Conservatives to question asylum seekers and a very generous approach to immigration will be fodder for Liberal election strategists, and Conservative Leader Andrew Scheer must keep his troops from unfortunate anti-immigrant outbursts which would be fully exploited by the Liberals. It will remain a stretch, however, for Liberals to depict Conservatives as anti-immigrant.

Scheer might consider that there are solid non-racist arguments to be made against increasing immigration levels—a view held by many in his base. A recent New York Times opinion piece by David Leonhardt quotes labour historian Irving Bernstein: “Immigration restriction, by making unskilled labour scarcer, tends to shore up wage rates.” In addition, Leonhardt makes the point that the period of strongest income gains for middle class and poor families in the U.S. followed and overlapped with a period of falling immigration.

Every campaign needs to show its leader and policies superior in every way to its opponents. Trudeau consistently insists that he opposes the tactics of fear and division, and he knows he will benefit from the widespread dislike of the only populist government in Canada, that of Doug Ford in Ontario. Ford’s refrain “for the people” against elites is pure populism. Liberal canvassers in Ontario are hearing lots of anti-Ford sentiment at the door.

Recent patronage scandals brought on by Ford’s former chief of staff, Dean French, and a series of damaging cuts to education and other services, have seriously tanked Ford’s approval to the point that it is now generally agreed that Scheer’s popularity in Ontario has suffered as well and that he will steer well clear of Ford in the election.

Anti-populist sentiment could well become a permanent part of the Liberal pitch. Will Trudeau position himself as the bulwark against the threat of authoritarianism, Trump-style populism and anti-immigrant xenophobia invading our peaceful land? It’s tempting, to be sure, particularly given how his stump speech is built. On the other hand, will Scheer and Rempel turn up the volume on Trudeau’s missteps in immigration and asylum seeker policymaking? Likely, but with great care.

Racism and xenophobia are powerful moral issues and there is little doubt that racism remains a problem in Canada—most notably in highly publicized cases in several police forces. Racism against Indigenous people is a huge problem, too. Trump’s telling the four Democratic congresswomen of the progressive “Squad” to go back where they came from provoked a flood of social and other media from Canadians sharing similar stories. “We can do better” however, sounds very much like the 2015 Trudeau.

It could be argued that a form of populism has already taken root in Canada. That is the idea of a pure people being exploited by a corrupt elite. What Washington Post columnist George Will has called “curdled envy and resentment.” This is certainly evident in attitudes in Western Canada, particularly Alberta and Saskatchewan, against the Ottawa, Toronto and Montreal elites.

As Andrew Potter from McGill University has argued in the Globe and Mail: “This is populism of a highly regionalist sort… the worrying over whether the right-wing populists will take power in Canada misses the fact they already have. They’ve merely taken to the provincial level of politics to air their grievances and accomplish their goals.” Could this be countered by the Liberals in a strongly worded national unity pitch? We will see. The Conservatives will certainly use Trudeau’s fight with provincial premiers over the carbon tax in their attacks on the government.

All in all, despite the attention being given to populism and authoritarianism from Hungary to Britain and Brexit to Trump’s America, it is difficult to argue that Canada, with its entrenched multicultural multiracial communities, will yield to these trends, or that the fear of populism will be a decisive factor in the next election.

Patrick Gossage, press secretary to Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau from 1976-82, is the author of Close to the Charisma: My Years between the Media and Pierre Elliott Trudeau, and founding chair of Media Profile, a Toronto media consulting and PR firm.