Could Health Care be on the Ballot Again?

Health care is arguably the second-most politically charged issue in Canada after pipelines. It is the cornerstone of a social safety net that Prime Minister Brian Mulroney once famously called a “sacred trust” between Canadians and governments of all parties. This election season, the more precise ballot question may be pharmacare.

Shachi Kurl

Health care may be a revered Canadian value, but it has been more than 20 years since it’s had the potential to become an actual ballot issue in a national campaign.

Arguably, the last time issues of health care access, treatment, coverage and funding elbowed their way onto the election agenda was 1997, when the Liberals, then led by Jean Chrétien, found themselves on the receiving end of acrimony rather than applause for announcing during the first week of the campaign that they would cancel planned cuts in health transfers to the provinces. But even then, the coverage and criticism had more to do with the timing of the move than with health funding policy.

Since then, health care has not exactly been the driving issue for voters. This year may be different. For the first time in a long time, federal party leaders are finding themselves compelled to say something about our physical well being.

In June, the Trudeau government’s Advisory Council on the Implementation of National Pharmacare submitted its report to Parliament recommending the creation of a new drug agency that would expand the list of prescription medicines covered by the taxpayer at an eventual cost of $15 billion a year. Trudeau endorsed the council’s recommendations, which essentially double down on the pharmacare provisions of the 2019 federal budget. In August, the government unveiled a plan to reform the regulation of prescription drugs to reduce patented drug prices.

Also in June, the NDP unveiled its party’s platform, including a universal pharmacare program, with plans to eventually see coverage for dental care, eye care, hearing care and other costs enshrined in the Canada Health Act.

In August, Conservative Leader Andrew Scheer, if elected promised to increase health and social transfer payments by at least three per cent a year. He said he was making the commitment to dispel any suggestion from his opponents that he would cut spending.

Usually, politicians—and their war room strategists—start paying attention to an issue once they’ve figured out it’s important to their potential voting bases. Crucially, for Canadians over 55—the very ones who may be reliably counted on to actually vote—their lived experiences interacting with the systems meant to safeguard and improve their health reveals a structure showing signs of flu-like symptoms.

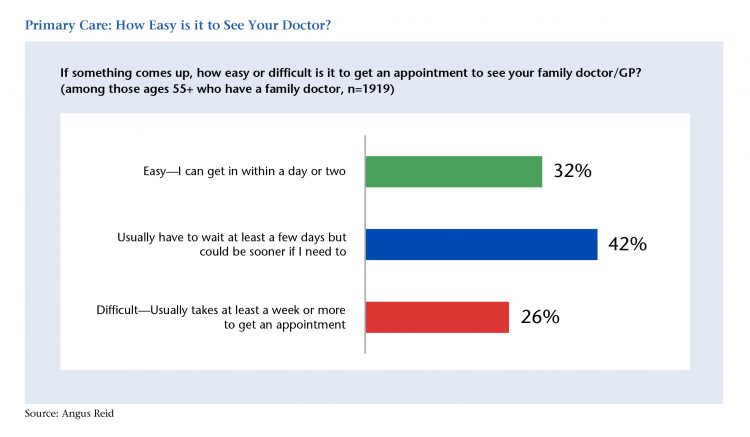

A comprehensive study from the Angus Reid Institute finds one-in-five Canadians aged 55 and older, upwards of two million people, report accessing primary care has been a significant problem. Challenges run the spectrum from having difficulty seeing a family doctor or GP (26 per cent say this), to waiting for advanced diagnostic tests, an appointment with a specialist, or surgery. They are also twice as likely to say the quality of health care in their own province is deteriorating rather than improving.

A comprehensive study from the Angus Reid Institute finds one-in-five Canadians aged 55 and older, upwards of two million people, report accessing primary care has been a significant problem. Challenges run the spectrum from having difficulty seeing a family doctor or GP (26 per cent say this), to waiting for advanced diagnostic tests, an appointment with a specialist, or surgery. They are also twice as likely to say the quality of health care in their own province is deteriorating rather than improving.

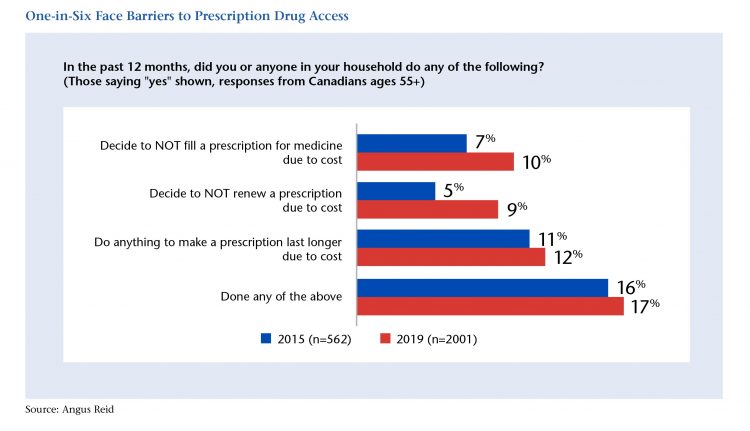

Of course, after the visit to the doctor, there is also the follow-up, which often includes prescription medication. When the Institute first looked at the issue of affordability of doctor-prescribed drugs four years ago, it found one-fifth of Canadians overall, and 16 per cent of those over the age of 55 were skipping doses, splitting pills, not refilling or simply not filling prescriptions at all, due to cost.

Four years later, this struggle for a significant segment of the country is ongoing, especially for those with household incomes lower than $50,000. Where you live also makes a difference, with those in Alberta and Atlantic Canada most affected. Little wonder then, that politicians are sensing Canadians’ anxiety, while also anxious themselves to find a way to gain political advantage by talking about it.

The intersection of health care and politics is more complicated. Conversations about “health funding” and “health coverage” are complex and varied, and thus hard to sum up in a sound bite. Politicians and political analysts would do well to remember that when talking about “health care”, they need to be focused on “whose health care?”. For aging Canadians, it may well be orthopedic issues, dementia and end of life care. For young women it may centre on fertility. For parents, the primary concerns will be focused on the health and thriving of their young children. Health is deeply personal and proprietary.

Of course, as much as some parties may wish to define health care as a ballot issue in the upcoming election, it is impossible to know what exactly will move voters until we are into the thick of the campaign. Will the ghosts of SNC-Lavalin come back to haunt the Trudeau government? Will the performance and leadership of Scheer and Singh be deciding factors? One way or the other, health will be part of the 2019 election discourse. The extent to which voters make their decisions based on it remains to be seen.

Contributing Writer Shachi Kurl is Executive Director of the Angus Reid Institute, a public opinion and research firm based in Vancouver.