Could Fiscal Transparency Work in Uganda?

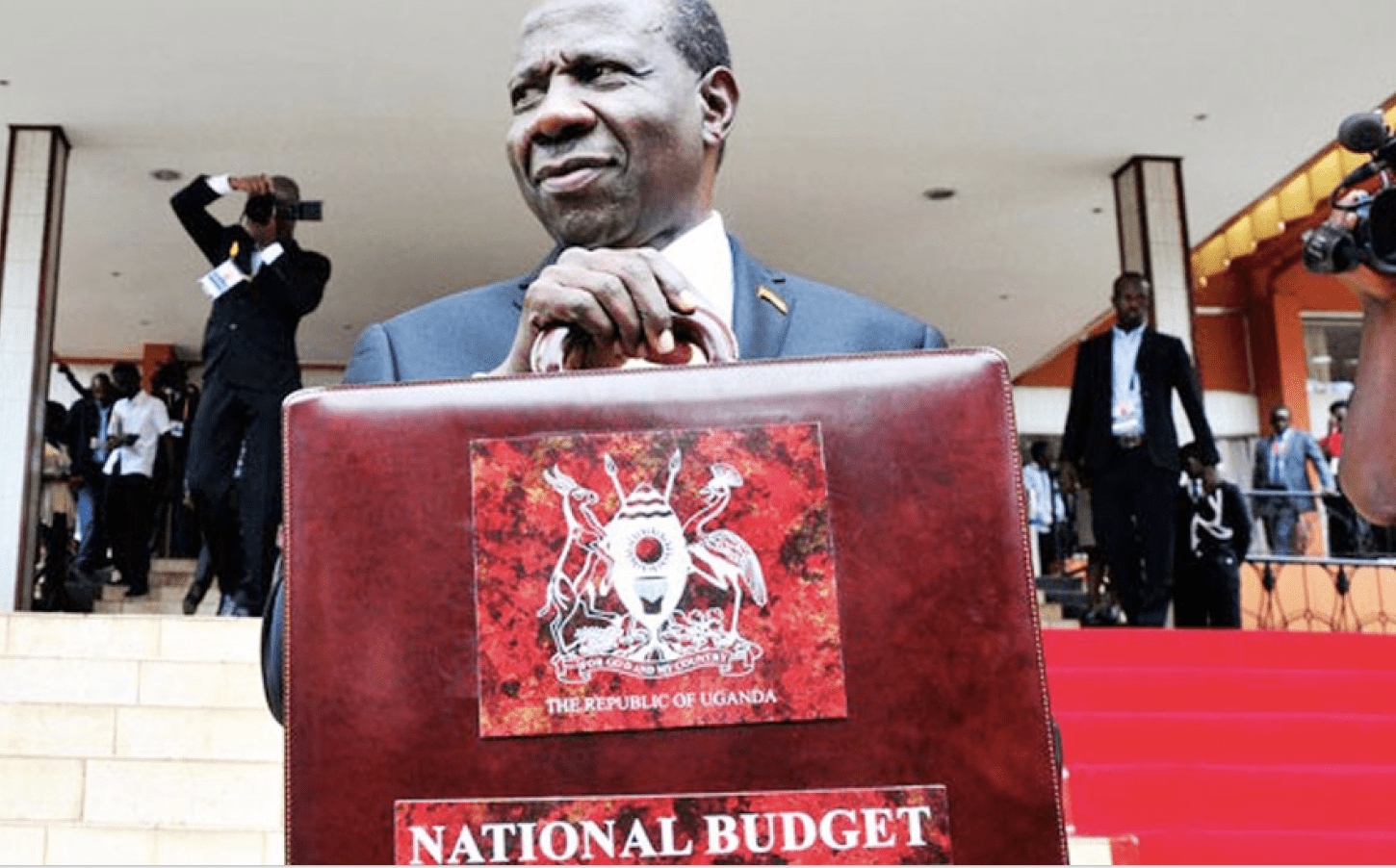

Ugandan Finance Minister Matia Kasaija with the Budget Box on Budget Day, June 15, 2023/Nile Post

Ugandan Finance Minister Matia Kasaija with the Budget Box on Budget Day, June 15, 2023/Nile Post

March 31, 2025

With so many issues afflicting Uganda, fiscal accountability is generally not on the Western media radar.

Transparency is widely considered the cornerstone of democratic accountability, fostering trust between governments and their citizens. However, as Niall Ferguson argues in The Great Degeneration, institutional decay stemming from weak governance, inadequate rule of law, and declining civic engagement can undermine trust even in systems that claim to be transparent. Uganda faces this challenge, whereby efforts to improve fiscal transparency have not bridged the trust gap. By learning from Canada’s robust fiscal transparency practices, Uganda can create a governance model that fosters accountability, citizen participation, and institutional resilience, addressing the systemic barriers that undermine trust in its democratic institutions.

Uganda has made strides in fiscal transparency through initiatives such as the Public Finance Management Act (2015) and the Ministry of Finance’s Open Budget Portal. However, Uganda’s score of 41/100 in the 2021 Open Budget Survey (OBS), while above the sub-Saharan Africa average of 31, falls short of the global average of 45 and lags far behind Canada’s impressive 87.

As Ferguson warns, transparency can expose institutional weaknesses, potentially deepening public cynicism if not accompanied by meaningful reforms. Uganda provides a clear example: while publishing budget allocations exposes critical fiscal data, it also highlights inefficiencies and corruption. High-profile scandals, such as the misuse of funds for health care and education, have eroded public confidence due to a lack of accountability, exacerbating disillusionment rather than rebuilding trust.

The Opposition’s alternative budget for 2025/2026 is set at UGX 55.7 trillion, notably lower than the ruling government’s UGX 72.1 trillion proposal. This difference underscores their claim that corruption and mismanagement are inflating public expenditure without translating into effective service delivery. Such claims, coupled with those from the Office of the Auditor General, only vindicate how the duty of transparency and trust should be a paramount consideration in fiscal policy design, communication and implementation.

Lessons for the Ugandan Government:

- Institutionalizing Public Participation: By adopting practices like Canada‘s, Uganda could foster inclusive governance through formal mechanisms, inviting public participation in budget formulation and execution.

- Simplifying Fiscal Information: Canada stands as a model in the realm of fiscal transparency, effectively bridging the gap between complex financial information and public understanding through clear summaries, visual infographics, and interactive tools.

- Enhancing Accountability and Combating Corruption in Procurement Practices: Strengthening oversight mechanisms and tackling corruption in procurement are vital for ensuring accountability and integrity in governance. By enhancing the independence and capabilities of oversight institutions such as the Auditor General and fostering transparency through real-time publication of procurement data, Uganda can cultivate an environment of trust and clarity.

- Investing in Civic Education: Canada’s strong civic engagement stems from effective civic education programsthat enable citizens to hold their government accountable.

Reversing institutional decay necessitates addressing systemic deficiencies through meaningful reforms. In Uganda, this entails moving beyond mere transparency to confront the root causes of public distrust, such as accountability failures, corruption, and limited civic involvement. By adopting strategies similar to Canada’s, such as enhancing public participation, clarifying fiscal information, bolstering oversight, and fostering a culture of accountability, Uganda can transform transparency into a means of empowerment.

Nickson Mugabi, currently an MPP candidate at the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill University, hails from Uganda and holds a law degree from Makerere University. With extensive experience in human rights advocacy from his previous work with the National Unity Platform Uganda, he is dedicated to advancing information integrity, democratic governance, and inclusive policy development and committed to crafting evidence-based solutions that drive meaningful change for underprivileged communities.