Coercive Diplomacy and the Smug Bugger Factor

The use of intimidation, triangulation and dubious quid pro quos to produce outcomes that consolidate power rather than serving the people isn’t diplomacy, it’s corruption.

Lisa Van Dusen

September 8, 2020

We’ve all seen governance and human rights norms incrementally weakened or obliterated recently to meet totalitarian standards rationalized by China’s geopolitical ascendancy but benefiting quite a few other interests. The latest instrument of this trend is “coercive diplomacy”, the diplomatic version of “illiberal democracy” — also oxymoronic, contagious and euphemistically designed to cover a multitude of crimes and misdemeanours.

In its pre-new world order incarnation, coercive diplomacy was defined as the leveraging of asymmetrical military might — usually implied or threatened — as a means of changing the behaviour of a rogue state or situationally belligerent, intractable actor. As with so many things that have been repurposed, reinvented and bastardized for thuggish exploitation — democracy, social media, the presidency of the United States — the new coercive diplomacy has more to do with what The Economist calls China’s “sharp power”, what China itself quaintly calls “wolf warrior diplomacy” and what, in its American adaptation, is one more thing attributed to Donald Trump’s personality that really has nothing to do with it.

In a recent report titled The Chinese Communist Party’s Coercive Diplomacy, the Australian Strategic Policy Institute — based in Beijing’s Number One coercive diplomacy target with Canada, per the ASPI, being Number Two — the authors write: “The CCP’s coercive tactics can include economic measures (such as trade sanctions, investment restrictions, tourism bans and popular boycotts) and non-economic measures (such as arbitrary detention, restrictions on official travel and state-issued threats). These efforts seek to punish undesired behaviour and focus on issues including securing territorial claims, deploying Huawei’s 5G technology, suppressing minorities in Xinjiang, blocking the reception of the Dalai Lama and obscuring the handling of the Covid-19 pandemic.”

As Matthew Fisher wrote in his piece for Global News on the report, “President Xi Jinping’s frequent modus operandi is to have foreign ministry spokesmen, ambassadors and state media insult, menace and use inflammatory language against countries that displease it. These presage reprisals such official bans on agricultural products and unofficial boycotts on automobile exports.”

If you substitute “Donald Trump” for Xi Jinping in that sentence, it conjures Peter Navarro’s content drops disparaging Canada, Trump’s abuse of tariffs as a form of punishment against Canada on entirely unrelated files and the use of Trump’s Twitter account as a weapon for bullying and coercion against a range of geopolitical actors, including Canada. (I’m certainly not the only columnist to have pointed this out, but Trump’s pre-election, anti-China rhetoric belies an impressive record of doing Beijing’s anti-democracy, new world order bidding).

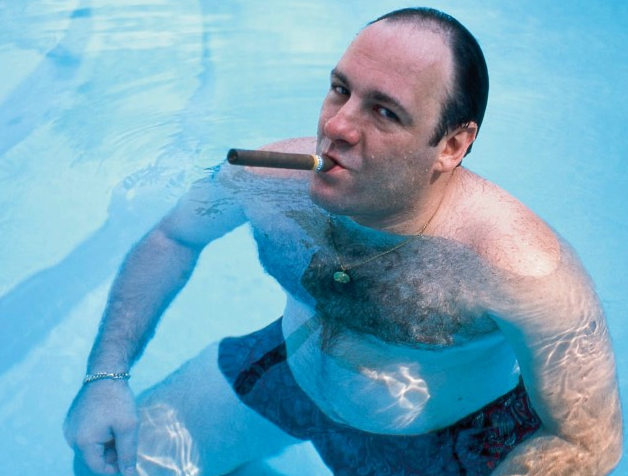

In basic power terms, the new coercive diplomacy isn’t all that new. It replicates the punitive triangulation, veiled and not-so-veiled threats, proxy weaponization, leveraged corruption and covert tactics of morally murky organizations from the Borgias to the Cosa Nostra to Tammany Hall to more recent political machines.

The key differences are, first, that China and its affiliates have imported thug tactics into the realm of high-level international diplomacy, where subtlety, civility and nuance have long been key negotiating and outcome-securing commodities. Second, Beijing has filled the public sphere with loaded propaganda language that would never have been used behind closed doors in normal diplomacy, and which instead amplifies intimidation as a wider deterrent. Third, the new coercive diplomacy embraces not just the deterrence and punitive behaviour-modification models of the Gambino family, it stops just short of their most notorious conflict resolution methods by leveraging the extrajudicial abduction and incarceration of hostages as a form of diplomatic coercion. What it shares with previous examples is the consolidation and perpetuation of power for power’s sake, not to benefit the citizens of any country, which is why it will be much easier to get away with once the same players have eliminated democracy.

Let’s call it the “Smug Bugger” factor — actors who behave as though they answer to no-one, which isn’t true, and certainly not to voters, which is becoming increasingly true.

More broadly, the new coercive diplomacy exploits implicit asymmetrical power to further disrupt the global balance toward thugs and authoritarians, a practice increasingly widespread in a world where so much of the otherwise inexplicable swagger of proxy players such as Trump, Boris Johnson, Nicolas Maduro, Rodrigo Duterte, Jair Bolsonaro, and other disruptive actors is informed by corrupt, covert narrative warfare capabilities that have enabled far greater and more destructive coercion than military hardware ever did. Let’s call it the “Smug Bugger” factor — actors who behave as though they answer to no-one, which isn’t true, and certainly not to voters, which is becoming increasingly true.

The two most recent examples of American coercive diplomacy are the misnamed “Middle East peace deal” involving the Trump administration, Israel and the United Emirates and the “Balkan rapprochement deal” involving the Trump administration, Israel, Serbia and Kosovo. In the new world order system of back-scratching strange bedfellows that, again, is simply a scaled-up, cyber-enhanced version of pre-existing corruption models, coercive diplomacy was used in the first case as part of a pattern to further the corruption-capture of erstwhile Palestinian allies and isolate the Palestinian Authority. In the second case, to secure the norm-altering quid pro quos of two new embassies in Jerusalem for a country whose democracy has been rendered all-but unrecognizable over years of corruption-enabled degradation fronted by Benjamin Netanyahu.

It’s the sort of previously unthinkable coercive diplomacy that is no doubt facilitated by US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s upskilling in the ways of narrative engineering during his tenure as CIA director and the fact that, on his arrival at Foggy Bottom, he purged the conventional, diplomacy-versed diplomatic brain trust of the United States.

It all seems imbued with a confident assumption on the part of the Trump administration that it will not only, corruptly and against all common sense, prevail in November. And that it will never again have to submit to the inconvenience of authentic democracy.

Lisa Van Dusen is associate editor of Policy Magazine and a columnist for The Hill Times. She was Washington bureau chief for Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News, and an editor at AP in New York and UPI in Washington.