Climate Policy Post-COP26: Finally Catching Up with the Future

As with prizefights and campaign debates, United Nations Conference of the Parties meetings, or COPs, are burdened by the weight of expectations before the gavel even goes down on the first plenary. Earnscliffe Principal and climate policy expert Velma McColl was in Glasgow during COP26, and outlines how the policy action produced during the conference lines up with where the world needs to be.

Velma McColl

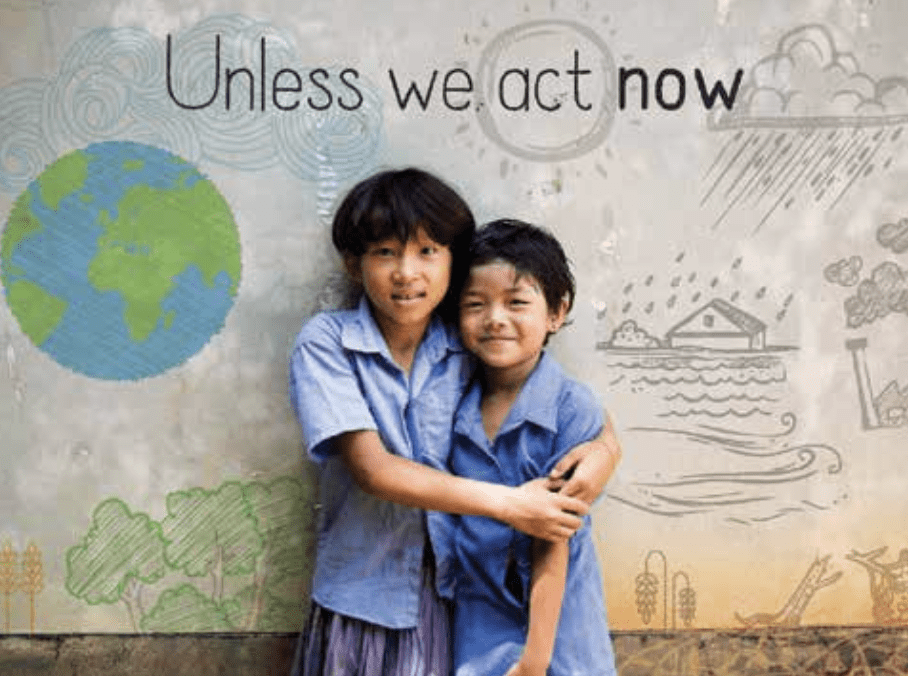

One purpose of leadership, exceptional leadership, is to represent the future to the present. This is as true in our roles as parents when we see the future sitting at our breakfast table each morning, as it is in our roles in our communities, in business, in the rest of our professional and personal lives. With climate change this year, understanding our future has moved from some distant concept to something more immediate, more urgent.

Around the world, changing weather systems have brought us face to face with the present-day consequences of accumulating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the atmosphere. What has been predicted by scientists for many years is unfolding before us, impossible to ignore as, around the world, homes burn or flood, lives are lost and communities are disrupted. A once-distant future is now our present, so the call for that kind of leadership is loud. Not surprisingly, the most adamant voices are those of the young people — mostly protesting in the streets — who will live decades into that future.

This was the backdrop for the COP26 climate summit, a necessary moment to implement the 2015 Paris Agreement’s successful global framework and ultimately limit global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Leaders arrived in Scotland with an understanding that we must limit the future compounding impacts of what we are living today and create a net zero future by 2050 and feeling the urgency, based on the science, that if we want to achieve the 2050 goal, we have to hurry up and reach a 45 percent reduction by 2030. Otherwise, consequences will multiply, costing our economies more money – in mitigation, disaster relief, insurance and lost opportunity – that will be sacrificed by the home owners of today and the taxpayers of the future.

The refrain of “1.5 to stay alive” from many small island states and countries in the global South echoed through Glasgow halls in November. But by the end of the conference, the 1.5 target was on life support. After 30 years of environmental and climate diplomacy, reaching back to the first Earth Summit in Rio in 1992 and the exceptional leadership of Gro Harlem Brundtland, we have made steady progress – but not at a pace that matches the weather impacts and not yet at a sufficient pace to transform the underlying energy, transportation, buildings and industrial systems that emit the GHGs we are trying to control. Not yet enough. Not enough action and not enough leadership.

But that’s not the whole story. Two weeks in Glasgow aligned global actors – governments at all levels, finance, business, many industrial sectors, Indigenous representatives, civil society and youth – toward two future inflection points – 2030 and 2050.

In Glasgow, we began to see the silhouette of collective leadership that would implement a shift toward the future with a series of initiatives to accelerate transitions that have been largely pipe dreams until now. We have needed public understanding, political will, technology capacity and capital flows to intersect, unleashing the necessary momentum for change.

It’s important to note a couple of important convergences in Glasgow. First, science got integrated with global reporting. After science guided us through a global pandemic, the majority of us now understand that climate science is not the terrain of political debate but a north star for action.

The 45 percent target by 2030 comes from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and is now what countries’ emissions reductions targets (NDCs) will be measured against. And we will be able to transparently measure progress against these targets every year in a public accounting system that tells all of us the score on meeting our global targets. We didn’t have this in 2015 and we can objectively acknowledge that everything to date it is not enough and not fast enough. These kinds of tools tend to force accountability and will motivate businesses now embracing environmental, social, governance (ESG) goals, as well as community leaders, innovators and an increasingly concerned public.

A second area of impact and convergence is that private sector finance, government climate finance, and the Paris Rulebook all now align to move capital markets, investment and technology deployment toward these agreed 2030 and 2050 goals. Under the leadership of Mark Carney and Michael Bloomberg, dating back to before 2015, more than $130 trillion in private finance is now aligning toward net zero by 2050, diverting capital toward renewable energy, batteries, critical minerals, electrification, clean technology, negative emissions, climate resilient buildings and more.

They are steadily moving away from what they see as riskier high-carbon investments such as fossil fuels – and in some ways, this move in capital markets is more significant than the brinksmanship that happened in Glasgow around “phase-down” versus “phase-out” of fossil fuels and coal. Banks and financiers will reflect these shifts every day, with boardrooms deciding what kind of projects and infrastructure get a green light and what gets rejected, a feedback loop that has far more bite for global and sectoral industry players than diplomatic language.

On the government side, greater certainty was provided by the global North (wealthier countries) to guarantee $100 billion to the global South (developing and emerging countries) for investments in climate-friendly technology and infrastructure. There was a recognition that countries living on the frontlines of coastal flooding and climate impacts should be free to invest in adaptation to climate change, a somewhat obvious point but an important win.

And the last part of this trifecta to move resources and decision-making toward a low-carbon future is, finally, the details of the Paris Rulebook and Article 6, which establishes global standards and reporting for how carbon offsets will be defined. It also sets the architecture for a single, integrated carbon trading market, guiding actions by both government and the private sector.

Together, these areas accelerate the flow of capital away from status-quo systems and toward the development and deployment of net zero technologies, and speed changes in industrial processes and electrification and in nature-based solutions in forests, agriculture and food production. They also create a space to include nature fully in the climate debate as an end in itself, something that enhances our lives and the health of the planet, creating efficiencies by removing an arbitrary barrier to major solutions around where carbon is stored in our earth, land and ocean ecosystems.

The challenge in Canada, and in every other country in the world, is to now deliver, to show the leadership to our children and fellow citizens that we can do what we promised. There is no getting around the fact that young people are anxious and disillusioned about the world we are leaving them, particularly on climate.

As the mother of a university-aged daughter, it is uncomfortable and requires humility to justify 30 years of incremental progress. We can’t deny the numbers, it’s simply not enough. And politicians and governments are going to have to own that, too.

It’s part of the reason why Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, on the hustings in the last campaign, was so surprised when the Liberals were judged to be failing on climate. They have implemented a carbon price, made the most detailed, complete promises and funding strategies of any government in Canadian history, but with atmospheric rivers, flooding and road closures in British Columbia, we can all see that targets and promises are not enough. Glasgow is over but we have regular reminders of the need to act, from weather changes, Fridays for the Future protests, and from our wise Governor General, Mary Simon, drawing on her lived experience in the Arctic, calling out that “our earth is in danger”.

The world is at a moment of reckoning. Patience for excuses is running out. Matched with the Paris Agreement and in anticipation of the Glasgow summit, Parliament passed the Canadian Net Zero Emissions Accountability Act, requiring that a detailed 2030 emissions reduction plan be tabled by this March. Environment and Climate Change Minister Steven Guilbeault has just launched consultations on how to transition to a zero-emission electricity grid and 100 percent zero-emission passenger vehicles by 2035, electrify medium and heavy-duty vehicles by 2040, reduce methane by 75 percent by 2030 and, most pointedly, cap emissions from the oil and has sector to current levels and get to net zero by 2050.

In a mark of how much things have changed since 2015 when the Paris Agreement was signed, companies accounting for more than 85 percent of oilsands emissions have already committed to achieving this goal and hundreds more outside the energy sector have also jumped on board. Getting provinces, territories, cities and Indigenous leaders onside will be key. We will need to look to our business and finance community for leadership within our traditional and ermerging

sectors and there is an opportunity agenda for deployment of a wide range of world-beating clean technologies that Canadian innovators have developed here at home and can be exported to the world.

Looking decades ahead and taking the long view takes courage and leadership, putting the next generation’s interests ahead of our immediate needs.

There are leaders in all walks of Canadian society who are wrestling with these challenges, who are managing at the intersection of these trade-offs, being honest about the costs today and tomorrow. Decision-makers are starting to understand that the balance of consideration favours the future. Our politics needs to catch up with our increasing capacity for change and our policies must be more nimble, focused on quick wins and collaboration within the federation.

We’ve been making steady progress these last 30 years, taking baby steps, learning how to walk in an integrated-global system. Glasgow marks a permanent shift in our planetary understanding and has proved that we have many of the fundamental building blocks to make generational change. Canada can look forward and not fall into historic squabbles or betray our natural assets and opportunities, we have the tools here at home to capitalize on the right, future-forward choices. It’s time to be accountable, use every ounce of our collective ingenuity and run toward the changes across our economy that meet our 2030 goals – and on to net zero by 2050.

Contributing Writer Velma McColl, a Senior Principal of Earnscliffe Strategies, is a British Columbia native and environmental specialist who filed analysis for Policy from COP26 in Glasgow.