China In-Between: Ensconced in the Diaoyutai and Meeting an ‘Immortal’

Robin V. Sears

It’s rare to be able to pinpoint the moment when historic change first strikes. After a few years, and much guesswork, we can see roughly when it became obvious that penicillin or mobile phones were going to change the world. In some cases, that retrospective search for clues is helped by the indelible moments engraved on our brains from eventful travels.

I will never forget the midnight, hours-long private meeting in Havana with Fidel Castro in 1981 as part of a mission to Cuba led by Ed Broadbent. Or the meeting with Mikhail Gorbachev in 1985 — his first with foreign leaders since becoming general secretary of the Communist Party — with former German Chancellor Willy Brandt, then president of Socialist International, leading the delegation.

With Castro we saw a slower, weakened but still charismatic leader who, like his revolution, was on a downward slope. By contrast, we could see that Gorbachev was at his peak, but not quite yet that the reforms he would soon launch would ultimately topple the Soviet Union.

But it was a visit to Beijing in the fall of 1993 — as a staffer on a delegation led by Paul Desmarais Sr. that included former Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, who had retired just months earlier — that truly taught me the value of travel as a means of understanding and anticipating world events. That trip exposed me to the vast changes being wrought in China, but only looking back did I grasp the magnitude of the changes that Deng Xiaoping had set in motion.

It was an in-between time; the post-Tiananmen global freeze China had endured for the previous four years was nearing its end and the prospect of a thaw based on economic interests seemed reasonable, before the first two decades of this century recalibrated Beijing’s power calculations.

The first sign of changing times on that trip, which happened even before we took off for Beijing, startled me. A Power Corp. aide who was handling logistics for the tour called about a month before the mission’s departure. He said with the calm assurance of someone used to power: “Please call the following Chinese official and give him our plane’s details and our draft flight plans.” I responded rather anxiously: “I don’t think the Chinese permit overflights, let alone landing by private non-Chinese aircraft…” He said with a certain edge to his voice, “Just make the call, please. And you understand none of this is to be shared with the embassy or anyone else, right?” I swore myself to secrecy and hung up with mounting anxiety. I decided I had to do some homework before calling a senior Chinese bureaucrat. Messing this up would not soon be forgotten in Montreal or Beijing.

I called a former US diplomat I had become friends with during my years in Tokyo, asking him not to mention to anyone that I’d called. I described the request without naming any names, and expressed by doubts about the mission. He chuckled and said, “Well, you’re right, of course, but things are changing so quickly right now, your client probably knows more than you do about what’s possible.” He was right, they did. I made the call and dutifully reported back that I had conveyed the information and that there would be no problems. For a country that had lived in total isolation for the first decades of the revolution, still furious about the territories seized by foreign powers, and deeply sensitive to any foreign trespass today, this change was significant indeed.

I had been travelling to China for more than a decade by then. I had watched armies of cyclists replaced by small, dirty cars; stodgy Soviet-era limousines by Mercedes. Flashy Western-style hotels replacing the smoky, smelly, rundown 50s-era establishments. But this time was different in so many ways: the beginning of the explosion of affluence that shook China and the world over the next decade.

The Desmarais are Canada’s most China-connected business family. They had been visiting, then making investments in China, for more than a decade at that time. Nonetheless, when the Communist Party gave the go-ahead for their delegation to reserve the most prestigious villas in the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse compound and its surrounding parkland in Beijing, and to host a final thank-you dinner for the Chinese leadership, it raised eyebrows in Canada.

The magnificent houses and halls, the bubbling ponds overlooked by centuries-old stone bridges, and the immaculate grounds made a lasting impression. Built to house emperors more than 800 years ago, it was also used by Mao Zedong as well as his spymaster and enforcer, Kang Sheng, as his home and office, and centres of ‘interrogation’ after the revolution. Mao had also lived there.

The Diaoyutai was often used by Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders to welcome or say good-bye to foreign dignitaries. No one I asked could remember ever allowing foreigners to host events at this level themselves. It was evidence of the respect the Desmarais’ had acquired.

Suddenly, the former PM stopped in his tracks, and shouted ‘Boys, come here!’ Mulroney’s deep baritone at full volume would stop an elephant. Gesturing in front of him, he said, ‘Boys, I am going to introduce you to one of the most important men in this century in China, and in the world. Stand still!’

Only years later did I experience the epiphany as to what a powerful signal of change that event — and who had attended it — was. Walking from a conference hall to the dining room for the final dinner in the late afternoon, I caught up with Mr. Mulroney deep in discussion with a senior party leader. After a few minutes, approaching us came a small group of aged Chinese guests. Running alongside us, chasing each other, were two young boys, children of delegation members.

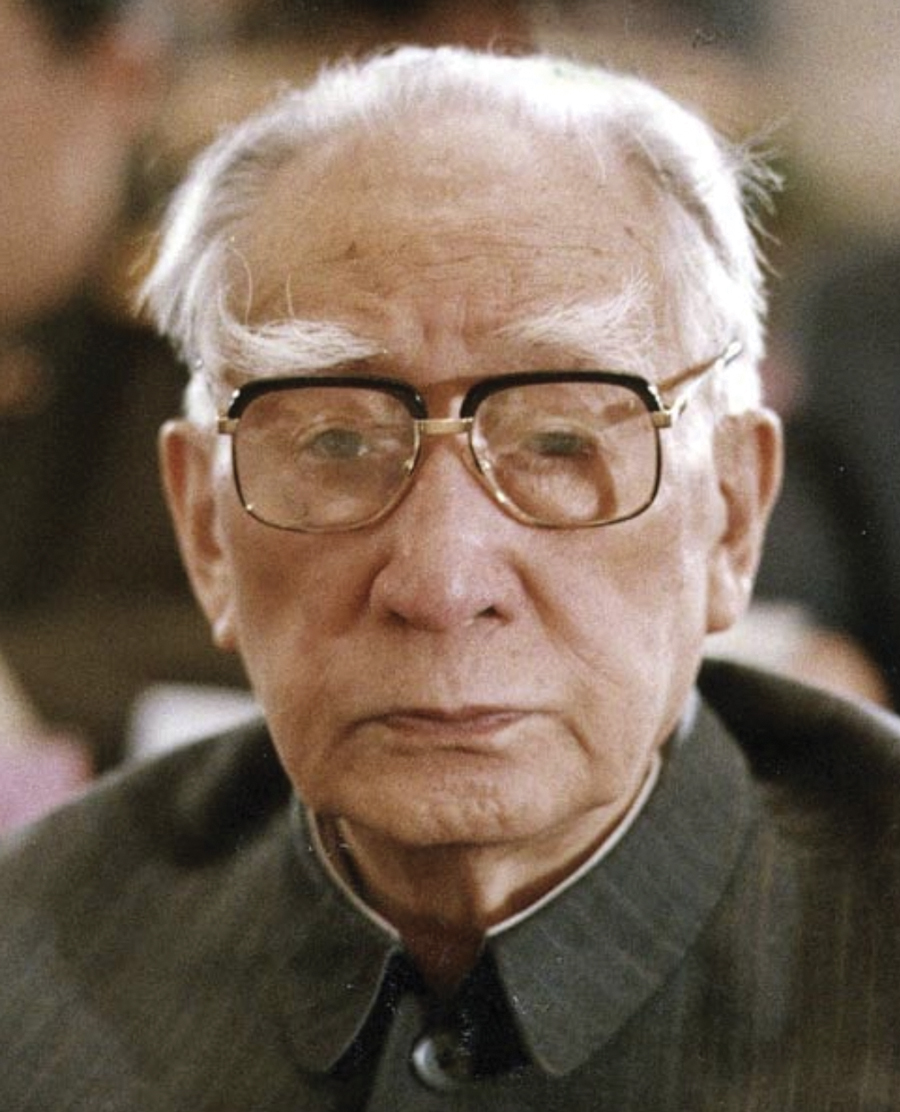

Suddenly, the former PM stopped in his tracks, and shouted “Boys, come here!” Mulroney’s deep baritone at full volume would stop an elephant. Gesturing in front of him, he said, “Boys, I am going to introduce you to one of the most important men in this century in China, and in the world. Stand still!” The obvious leader of the Chinese group approached us slowly. He was stooped with age, but his eyes were sparkling and intense, as he chatted with the boys. Former Vice Premier Bo Yibo was one of the “Eight Immortals”— Mao’s key lieutenants, veterans of the Long March, of the Yan’an caves, and of the first CCP government. He suffered badly in the Cultural Revolution, but returned to hold most of the senior positions in government in the 70’s and 80’s. He died as the oldest Party member at 98.

That Mulroney recognized him, that Bo was even attending this dinner at 85, and that he knew that the former prime minister was someone of sufficient importance that he went out of his way to treat the stunned young boys so respectfully, was all very surprising to me.

As I got to know Mr. Mulroney better — I’ve worked for him as an advisor during his post-prime ministerial years — I came to understand that he was an ‘old China hand’ himself. As PM, he had pushed then-External Affairs to develop a transformational strategic plan on Canada/China relations. He had had the savvy to know that post-Tiananmen bullhorn diplomacy was futile, instead sending in secrecy high-level personal representatives to Beijing. He had studied the revolution and its leaders for years.

That explained his great deference to an aging revolutionary. But I suspect he knew something I only puzzled out years later. Bo was a party conservative in many areas, but a determined economic moderate, fighting to improve China’s development through more open trade and investment. He was a key player behind the scenes in a battle Deng Xiaoping was waging with more rigid and isolationist leaders. He had praised Deng’s ‘Southern Tour’, which had taken place the previous year. Deng openly praised the booming Shenzhen private entrepreneurs on a surprise visit. That explained why Bo was greeting Brian Mulroney. The party, now led by Jiang Zemin, had rolled out this very old man to send a signal about which side the leadership was on.

Four years later, Paul Desmarais Sr. was granted a rare privilege: a long private meeting with Bo Yibo. Bo’s children ensure the family’s continuing influence in China. Each has paid leading a role in the economy, academe and foreign affairs. Sadly, his most famous son, Bo Xilai, a provincial governor, was jailed for life on corruption charges amid widespread rumours that he had also been caught plotting against Xi, working with a former security chief and a Politburo member from Chongqing. Bo Yibo’s son Bo Guagua, an Oxford PPE and Columbia Law School grad, was employed for several years by Power Corp.

So, the fall of 1993 was near the beginning of a period of innovation, experimentation and global networking for Chinese business, academics, bureaucrats and the state itself. That period came to a sudden end with President Xi’s arrival in office almost two decades later, which ushered in China’s latest relationship with the rest of the world.

Back in China recently, reminiscing over lunch at the famous Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents’ Club, with another veteran of those years. We shook our heads over how dramatically Deng had launched the most successful economic revolution in history. And how sad it is that now, much of the product of those efforts lay smashed on the ground, like debris from another era. The carefully nurtured international networks, the strong support for the private sector in China, and the more open dialogue permitted then, forbidden now. After a few seconds of silence my friend said, “The new China that we had the privilege to witness up close is now dead. I wonder if another will ever arrive?”

Watching Putin’s apparent lunacy unfold so tragically, China’s rising obsession over Taiwan, and the rebirth of the North Atlantic alliance, I wonder what private, high-level visits today would reveal about China’s road ahead, and ours.

Robin Sears is a crisis communications consultant, previously an NDP strategist for two decades. He spent twelve years in Asia, first as a trade diplomat and later as a management consultant.