Can’tLit? Complacency and Canadian Publishing Policy

Canadian authors are having a pan-generational, metacultural moment. Led by the stratospheric, genre-jumping, late-career phenomenon of Margaret Atwood’s ubiquity and boosted by internationally recognized writers from Michael Ondaatje to Esi Edugyan, Canadian literature today is not your grandmother’s CanLit. But as McGill-Queen’s University Press Executive Director Philip Cercone writes, beneath the Bookers and bonnets, publishers in a market this size still rely on government funding mechanisms, some of which contain fatal flaws.

Philip J. Cercone

To outsiders, it appears that Canadian authors and publishers in English Canada are flourishing: some 3,500 trade titles are published each year, approximately 72 percent of these issued by over 100 Canadian-owned independent publishers, with Canadian branch plants of multinational publishers releasing the rest. To insiders, the view is that we are being inundated by a tidal wave of non-Canadian titles in bookstores, libraries (whether they be public or housed by a university, college, or classroom), and reviews and media. Over the past few decades, the number of new titles has increased dramatically and, today, an educated guess is that over 700,000 titles in the English language are published worldwide each year, with some 60 percent of those published in the United States and 30 percent in the United Kingdom.

There are two major bodies of national scope that fund book publishing in Canada: the Department of Canadian Heritage and the Canada Council for the Arts. The latter is a federal Crown corporation accountable to Parliament through the minister of Canadian Heritage. Thanks to substantial funding from the Department of Canadian Heritage through the Canada Book Fund (CBF) and from the Canada Council for the Arts, and to a lesser extent from provincial programs and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), the industry has managed to remain stable and slightly profitable. Without government support, a vibrant publishing industry in this country would not be viable as multinational publishers have captured the best-selling Canadian authors who were first nurtured and published by small independent Canadian publishers. But not since the government of Brian Mulroney, when the Baie Comeau policy was announced and the Canada Book Fund was created, has there been a willingness on the part of the federal government to promote and foster Canadian culture, of which the writing and book publishing industry forms a part.

Four recent government initiatives to support the industry are the doubling of the budget of the Canada Council over five years; the restoration of funding for culture to Canadian embassies around the world; the funding of Canada as a guest of honour at the 2020 Frankfurt Book Fair, where the Canadian publishing industry and its authors will be the epicentre of this singular cultural showcase as the world’s largest annual trade book fair; and the investment in the Canada Book Fund of $22.8 million over five years to support accessible digital book production and distribution by Canadian independent publishers.

These initiatives on the part of the federal government are laudable and they will bolster the creative side of Canadian book writing and publishing, which is in good shape in all genres. Nevertheless, while supply is plentiful, awareness and readership have been in decline over the past decades. Further actions are needed.

Since the founding of the Canada Council 63 years ago, promotion and support for the Canadian writing and publishing community has been a cornerstone of its mission. Publishers worked in tandem with budding writers and, as a result, Canadian writers such as Margaret Atwood, Alice Munro, Michael Ondaatje, Marshall McLuhan, and Margaret MacMillan are household names around the world. Together we punch above our weight. Nevertheless, publishing has not benefited from the Council’s doubled budget as much as one would have thought.

Non-fiction has been downgraded and this puts some publishers at risk of their grants being frozen or not being funded at all if they do not attain the required minimum number of eligible titles. Indeed, some members of the publishing industry have been told directly by current senior Council leadership that it would prefer not to be funding publishers at all. Instead of expanding criteria to match its expanded resources, the Council has narrowed them, and it does not see some genres, specifically non-fiction, as contributing as significantly as fiction does to Canadian culture. At the same time, in a departure from longstanding practice, significant industry input on the direction of publishing support by the Council is no longer a given. The industries, both anglophone and francophone, are united in asking the Canada Council to restore its support for non-fiction to the same degree that it supports the other genres—fiction and short stories, poetry, drama, children’ and young adult literature, and graphic novels. Because the Council sees its mandate as “supporting the production of art works in the literary arts and the study of literature and the arts,” non-fiction publishing must be recognized as literary if it is to be supported.

Further, if a writer’s activity is funded at the research stage by the SSHRC, or if its publication is partially funded by SSHRC’s Awards to Scholarly Publishing Program (ASPP), the resulting book is not eligible for core publishing support, for translation grants, or for non-fiction Governor General’s Awards. The only Canada Council funding for which it remains eligible is Creating, Knowing and Sharing, the component that supports the arts and cultures of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples. An art history book on the Group of Seven, for example, if the research was funded by SSHRC, would not be considered eligible. But if it were funded by other organizations, it would be. Where are the logic and justification for singling out SSHRC-funded projects? Should this decision not be based on the book’s merits?

The Canada Council has always funded translations, but some eight years ago under the Harper government, it was given some additional $800, 000 a year by the Department of Canadian Heritage to have a programme totalling $1 million to fund translations from French to English or vice versa. Unfortunately, with its narrowing criteria, serious books of non-fiction, unless deemed literary, are no longer being funded for translation. Given this new departure at the Council, the Department of Canadian Heritage should redirect the $800, 000 and administer that amount itself or through other cultural agencies.

Before SSHRC was founded in 1978, the humanities and social sciences formed a division of the Canada Council. Now it is more closely aligned with the policies of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC). SSHRC funds some 180 publications through the arm’s-length Awards to Scholarly Publications Program of the Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences (CFHSS). This program, which has been in place for 80 years and preceded the Canada Council, now finds itself more aligned with the hard sciences, where journal and open access (OA) publishing—online, free of charge, usually with less restrictive copyright and licensing barriers—are the norm. But books in the human sciences are not the same as journals in the hard sciences and do not follow the same conventions.

At a recent meeting, SSHRC and the CFHSS announced a significant change to the current operation of their flagship publication awards program: they intend to transition the ASPP to a program that would require all awarded books to be published with open access. The exact implementation of this change has not yet been determined, but SSHRC has stated that it will not be accompanied by the additional funding such a move would require.

This policy shift will affect Canadian university presses, Canadian scholars, and the broader scholarly communications environment in significant ways. Most, if not all, of the 180 books a year the ASPP funds would never have been submitted to them under these conditions, because publishers cannot afford the loss of sales that would result from such a policy. In my view as executive director of McGill-Queen’s University Press and former director of the ASPP, this destabilization would be disastrous for the Canadian scholarly publishing scene.

Scholarly publishers are not opposed to open access, but when it is elected or mandated it must also be adequately funded. Significant numbers of scholarly titles in Canada are funded by publishers’ backlists, and with no backlist sales, OA books would need to be funded in the range of $30,000–$40,000 each. This model would also reduce publishers’ Canada Book Fund grants, which are allotted based on sales revenue. Finally, OA would put Canadian university presses at a further disadvantage compared with U.S. university presses and with Cambridge and Oxford, which are not moving towards an OA model. Instead of adopting a full-blown OA policy, SSHRC should launch a pilot project to see how some of those 180 publications can be published in that form and evaluate the results after three years.

Scholarly publishers are not opposed to open access, but when it is elected or mandated it must also be adequately funded. Significant numbers of scholarly titles in Canada are funded by publishers’ backlists, and with no backlist sales, OA books would need to be funded in the range of $30,000–$40,000 each. This model would also reduce publishers’ Canada Book Fund grants, which are allotted based on sales revenue. Finally, OA would put Canadian university presses at a further disadvantage compared with U.S. university presses and with Cambridge and Oxford, which are not moving towards an OA model. Instead of adopting a full-blown OA policy, SSHRC should launch a pilot project to see how some of those 180 publications can be published in that form and evaluate the results after three years.

Unlike the other bodies mentioned above, the Department of Canadian Heritage has implemented some enlightened publishing policies. Recently the Canada Book Fund, established some 40 years ago, was re-evaluated and the report correctly read the pulse of the industry to identify some needed changes. It found that its main support mechanism, the CBF, remains relevant and is effective.

Between 2012 and 2017, $175 million was allocated to publishers for the production, marketing, and distribution of Canadian-authored titles. The evaluation also identified some “unmet needs,” such as discoverability in a “crowded marketplace” and the promotion of Canadian books in the digital age. What is needed is an increase in the CBF’s budget, which has remained the same for decades, and funding to support the marketing of Canadian books in Canada. Canada being the 2020 host country at the Frankfurt Book Fair, where the publishing world shops, is highly laudable, but in 2021 we have to put more energy into ensuring that Canadian books are widely available in Canada.

Not identified in the report is succession planning, which is close to a crisis as the owners of about 20 percent of presses are nearing or past retirement age. We have to ensure that those companies survive and continue discovering and publishing new and established Canadian authors.

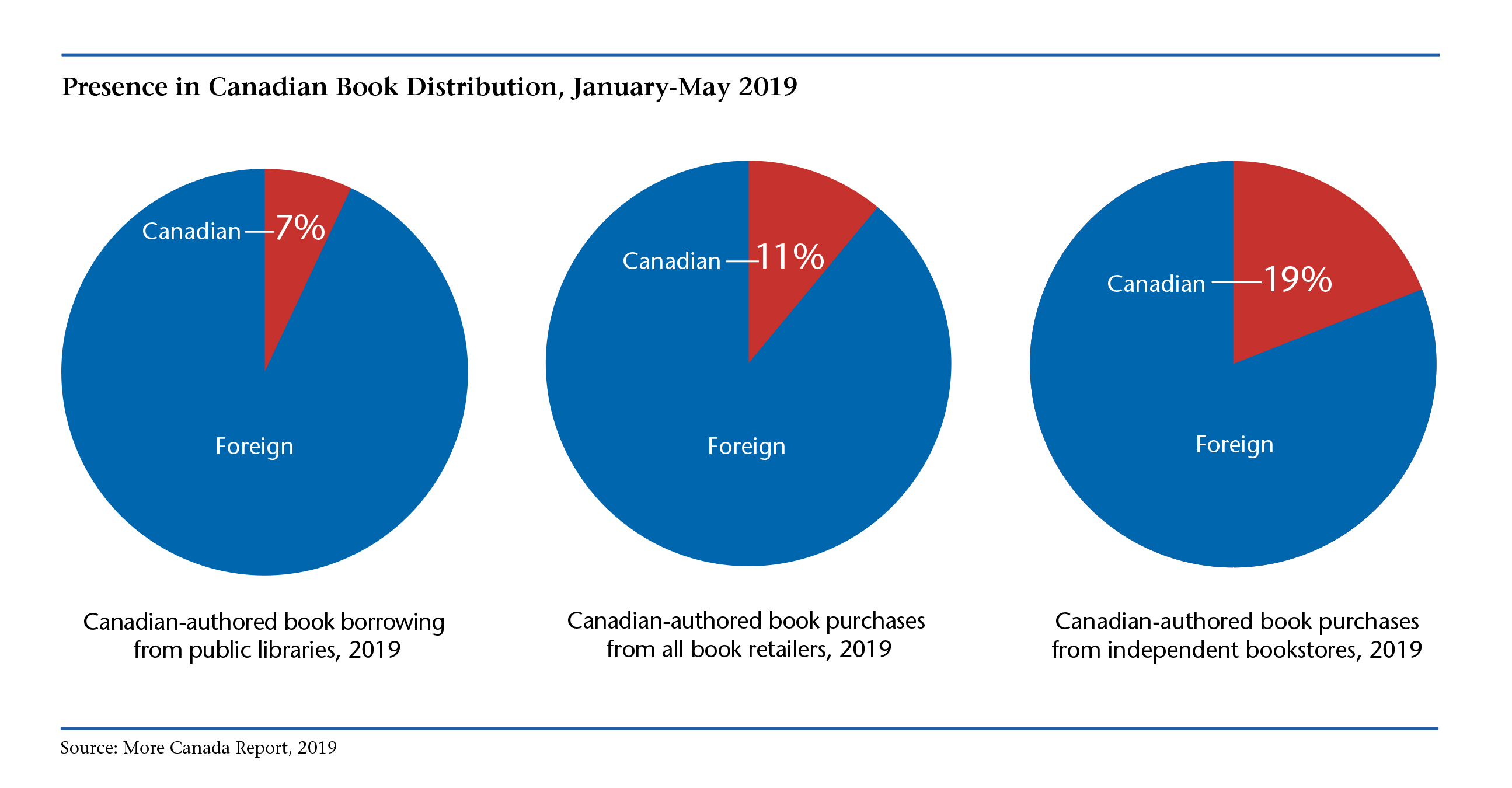

In December 2018, along with James Lorimer of James Lorimer and Company and Formac Publishing and Jeff Miller of Irwin Law Inc., I co-authored a 180-page report titled More Canada: Increasing Canadians’ Awareness and Reading of Canadian Books. The report is our distillation of the discussions of a task force we created to bring together 29 seasoned professionals with over 1,000 years of experience in publishing, bookselling, libraries, schools, and media, prompted by the disappearance of Canadian books from bookstores and library shelves across Canada. Unlike in Quebec, where provincial legislation regarding Canadian books protects their market share, in English Canada, while Canadian writers and publishers continue to account for large numbers of new books, their share of book sales has declined from 25 percent to 12 percent over the past 10 years.

The report has 68 policy recommendations, among which the eight most important are:

• Digital infrastructure that does not distinguish between Canadian and foreign books must be reworked.

• Financial support should be extended to independent bookstores, which do the best job

of bringing Canadian books to the fore.

• Public libraries are doing a superb job of encouraging book reading, but their software and their budgeting practices must be improved to help their users discover and borrow Canadian-authored books.

• Publishers must develop industry practices that give Canadian books a strong identity mark in the crowded marketplace.

• The industry must take action to support new independent English-language bookstores across the country, with a target of establishing 50 in the next five years.

• The Canada Book Fund should be expanded to support bookstore programming of events with Canadian authors, and to double public library spending on Canadian-authored books.

• Provincial governments need to implement accredited bookstore policies, adapted from a highly successful Quebec model that gives Canadian-authored and Canadian-published books great visibility and puts an independent bookstore in virtually every town and city in Quebec.

• New provincial support should be provided to expand the very popular “tree award” programs, which put new books by Canadian writers into the hands of tens of thousands of school-age kids every year.

Much has to be done to reinvigorate the English Canadian publishing world so that our culture is represented in all of its rich diversity. Industry leaders, government, and funding agencies need to do our part to ensure that we continue to create a literature we are proud to have in Canada and abroad.

Philip J. Cercone is Executive Director and Editor of McGill-Queen’s University Press, Canada’s premier academic and trade publisher, with offices in Montreal, Kingston, Toronto and Chicago. It is the only Canadian publisher with an editorial and marketing office in Great Britain.