Canada’s Trade Pivot: Engaging Asia’s Giants for Strategic Autonomy

The Port of Vancouver, Canada’s gateway to the lucrative Asia-Pacific market/Diego Delso, delso.photo

The Port of Vancouver, Canada’s gateway to the lucrative Asia-Pacific market/Diego Delso, delso.photo

By Stewart Beck and Carlo Dade

February 19, 2025

There is a larger challenge for Canadian trade and foreign policy looming just beyond the immediate challenges with the U.S.

How does a country that relies on trade for two-thirds of its GDP survive in a world where Donald Trump is fundamentally rewriting the rules and undermining institutions, ostensibly to favour U.S. growth at the explicit expense of others? A former ally in the fight for a win-win global economic order has turned into an economically dangerous competitor and threat to Canada’s ability to achieve prosperity at home and abroad.

There are two elements of the challenge Canada faces from this new status quo. The most well-understood is the tariff regime that is, among other ends, designed to force Canadian and foreign companies to move production, and hence jobs, from Canada to the U.S. This threat arises from the New Right, or economic populists in the U.S., such as Robert Lighthizer, Peter Navarro, and Oren Cass. Much has been written about this.

The second, less well-understood threat is the use of tariffs to force actions by trade partners to achieve goals beyond moving jobs from overseas to the U.S. These actions include forcing or inducing countries to align with U.S. foreign policy objectives, such as containing China, achieving U.S. immigration and territorial ambitions, or other aims. The new use of economic coercion goes beyond traditional uses of economic power, including sanctions, to force policy shifts by foreign powers that have committed generally recognized transgressions of international law. So far, trade policy under the second Trump administration is not that of a cop enforcing the law; it is that of a mobster conducting a shakedown and, most worrisome for Canada, forcing others to become accomplices in exchange for not being attacked and/or to maintain access to the U.S. market.

How does Canada respond to the potential loss of sovereignty or tarnishing of reputation associated with being a target of this coercion? We need to look to the lessons of today, not of the past, from our experience and that of others.

This is not as easy as it sounds.

A most important object lesson in the perils of the new U.S. policy framework from the last Trump administration that has been absent from current Canadian policy thinking is the country’s “China betrayal” at the hands of the last Trump I.

Trade policy under the second Trump administration is not that of a cop enforcing the law; it is that of a mobster conducting a shakedown.

During the renegotiation of NAFTA, the Trump administration inserted, at the last minute, a clause stating that any party to the agreement could withdraw if any other party entered free trade negotiations with a non-market country, a turn of phrase used only by the Americans. That any party to the agreement has, and has always had, the right to withdraw for this or any other reason made this wording in the new agreement unnecessary. The purpose of the insertion was not technical; it was psychological, to instill fear to align with U.S. policy on China.

This seemed unnecessary, as Canada largely agreed with U.S. policy toward China. Yet, aligning with U.S. policy and acknowledging this alignment in treaty did not protect Canada from unilateral action. In this case, the U.S. signed its own trade agreement with China with negotiated rules that favoured U.S. exporters, and especially agricultural exporters, at the expense of Canadians.

The threatened imposition of 25% tariffs on virtually all Canadian goods by the Trump administration is an unprecedented action against us, a trusted ally. This isn’t just another trade dispute — it’s a fundamental challenge to Canada’s economic sovereignty that demands a serious rethink of how we manage our international relationships. While Canada has developed an Indo-Pacific strategy, current diplomatic tensions have effectively sidelined meaningful engagement with China and India — the region’s two largest and most important markets. Events have put us in this situation, but our hampered engagement with alternative markets becomes even more critical as we face mounting economic pressure from the United States.

We need to learn from nations that have successfully navigated the challenges of maintaining independence while engaging with major powers. India’s path is instructive. From its historical role as a leader of the Non-Aligned Movement, India’s foreign policy has evolved to what External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar describes as: “Seek convergence with many, congruence with none.” This framework — keeping multiple strategic partnerships while avoiding complete alignment with any single power — provides a model for protecting Canadian interests in an increasingly complex world.

The implications of our current vulnerability are severe. A 10% tariff alone could trigger a Canadian recession; at 25%, we face an existential economic threat. The Trump administration’s justifications have shifted repeatedly — from border security to drug trafficking to trade deficits — despite data showing that the U.S. keeps a trade surplus with Canada when services and energy exports are included.

Canada has significant advantages and potential options in pursuing a more diversified international strategy, particularly in Asia, Latin America and elsewhere. Unlike many Western nations, we carry no colonial legacy in the region — a meaningful distinction that allows for more straightforward diplomatic and economic engagement. Our reputation for multilateralism and our multicultural society provide additional credibility in building new partnerships. These countries also face renewed pressure to diversify their dependency, reliance or even simple exposure to importing critical inputs from the U.S.

In this, Canada’s value proposition has shifted from simply being another source of materials and inputs to potentially being a source that is not the temperamental, unpredictable, and vindictive U.S., subject to the whims of not only the Trump administration but an increasingly isolationist and hostile U.S. Congress. Canada may be difficult and frustrating on the front end of negotiations and building capacity, but on the back end, once something is built or agreed upon, there is certainty.

But that certainty only exists if Canada can exercise the sovereignty to ensure it.

This was certainly the case in the late 1950s and early 1960s when the Diefenbaker government deliberately chose not to adhere to the U.S. embargo of grain sales to China during that country’s greatest famine, and despite threats and economic coercion from the U.S., Canada had suffered catastrophic losses of grain sales to foreign markets at the hands of the Americans, and the Diefenbaker government decided that enough was enough. It made no sense to embargo a country experiencing famine, especially if it was a country where Canada had just begun to sell grain.

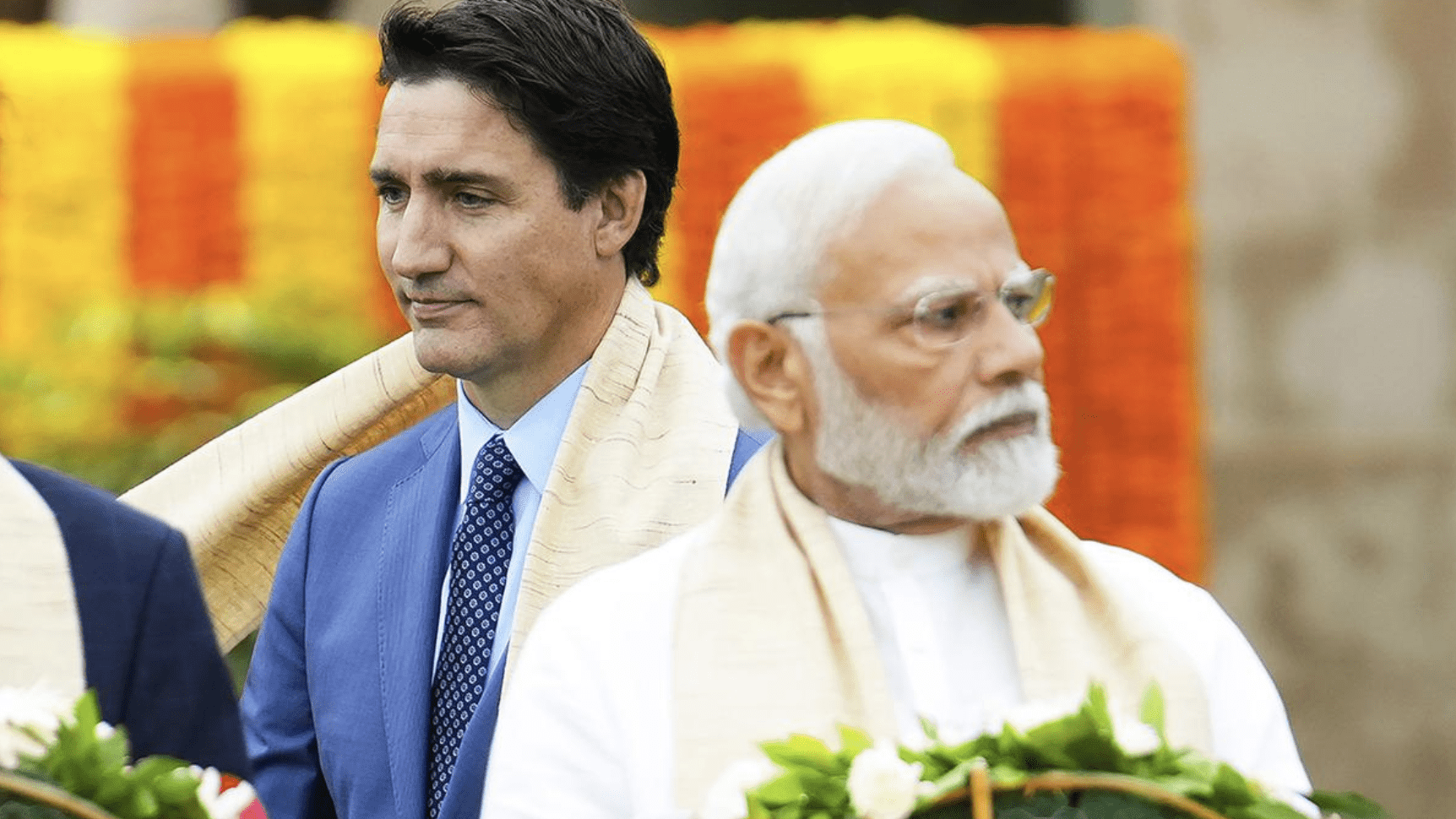

Canada must include China and India in a necessary pivot to Asia, write Stewart Beck and Carlo Dade/AP

Canada must include China and India in a necessary pivot to Asia, write Stewart Beck and Carlo Dade/AP

This was a vital Canadian interest that was worth defending. Canada pushed back against the U.S. while it worked with the Americans to set up NORAD and NATO. The country managed to find a balance between maintaining relations with the U.S. while pursuing, at some expense, an independent Canadian foreign and trade policy that did not sacrifice Canadian interests or harm the country’s long-term reputation to appease American interest of the moment.

Our most significant strategic asset is our energy and natural resources capacity. Asia’s major economies, particularly China and India, require reliable access to these resources for their continued development. This is not theoretical: Canadian diplomats working in India can attest that, over the years, there has been significant interest in Canadian LNG exports from both our East and West coasts. Indian Oil Corporation’s investment in a major West Coast LNG project, though ultimately not proceeding to final investment, demonstrated genuine market demand.

However, these opportunities highlighted our own internal challenge: the difficulty in building pipeline infrastructure to tidewater. While leveraging our energy advantage may require moderating some Paris Accord commitments, we can balance these imperatives by investing substantially in emissions-reduction technologies. This approach allows Canada to serve as a dependable energy partner and a practical leader in climate innovation, and it provides geostrategic leverage in a complicated, multipolar world.

Today, however, the risks of deeper Asian engagement require careful consideration. Closer ties with China could expose Canada to a different sort of economic coercion, technology theft, and pressure on human rights positions. India presents its own challenges through regulatory uncertainty, protectionist policies, and domestic diaspora politics that, unfortunately, affect our bilateral relationship. The potential for infrastructure vulnerabilities and regional entanglements adds yet another layer of complexity to these relationships.

These manageable risks must be weighed against the current threat to our economic independence. The Trump administration’s willingness to use punitive tariffs and more severe pressure than in the past against allies shows the dangers of overwhelming dependence on a single market, particularly one increasingly prone to using economic leverage as a tool of coercion.

A strategic approach to Asian engagement requires sophisticated risk management frameworks. This includes developing robust investment screening mechanisms, protecting critical technologies and infrastructure, and setting up clear parameters around security and sovereignty issues. We need the institutional capacity to identify and counter economic coercion attempts, cyber threats, and influence operations. Most importantly, we need to move beyond the current limitations of our Indo-Pacific strategy to develop practical frameworks for engaging China and India, even amid diplomatic tensions.

Canada can keep consistent positions on democracy, human rights, and international law without resorting to virtue signaling.

This will mean devoting even more resources than we have become accustomed to. Japan, South Korea, and key ASEAN nations offer significant partnership opportunities that complement our engagement with China and India. Singapore plays a pivotal role as a regional financial and diplomatic hub, offering important strategic opportunities for Canada. Its sophisticated balancing of U.S. and Chinese interests while maintaining its own autonomy provides a masterclass in strategic diplomacy for middle powers.

Our energy strategy should leverage not just infrastructure and resources, but also our growing expertise in emissions reduction, carbon capture, and clean-energy technologies — capabilities highly valued by technologically advanced partners like Japan and South Korea, which are themselves leading investors in climate solutions. This comprehensive approach to energy partnership can strengthen our position across the entire region.

Our clean historical slate in Asia is valuable, but it must be paired with principled engagement. Canada can keep consistent positions on democracy, human rights, and international law without resorting to virtue signaling. This requires sophisticated diplomacy that builds productive relationships while protecting core values.

Sector-specific strategies should focus on areas of mutual benefit — agriculture, clean technology, sustainable resource development — while carefully managing sectors with national security implications.

Building institutional capacity for managing complex international relationships is essential. This includes creating specialized units for monitoring geopolitical developments, coordinating security and economic policies, and maintaining consistent positions despite competing pressures from major powers. Importantly, building meaningful relationships in Asia requires a level of competence that cannot be produced overnight. It is a generational project requiring sustained investment in language training, cultural understanding, and regional expertise. Success demands both significant resources and long-term dedication to developing these capabilities.

Critics will say deepening Asian relationships risks our U.S. partnership. But we need to be clear about what is happening: the Trump administration isn’t treating Canada like a friend or even a competitor, it is treating Canada like an adversary, using economic coercion to force Canadian compliance and dependence. The 25% tariffs aren’t about fair competition or legitimate trade disputes; they’re about leveraging U.S. economic power to limit Canada’s ability to act independently. Building stronger Asian relationships isn’t about choosing sides; it’s about maintaining our economic sovereignty and ability to make independent decisions in Canada’s national interest.

Others argue that engagement with China and India carries excessive risk in the current geopolitical environment. While these concerns deserve thoughtful consideration, energy and resource relationships can provide a stable foundation for managing more complex diplomatic challenges. When nations share fundamental interests in energy security, they often find pragmatic ways to resolve differences.

The imperative for action is clear. The unprecedented use of punitive tariffs against Canada has exposed the vulnerability of relying on a traditional ally and friend. As global power continues to shift eastward and international relationships become increasingly transactional, Canada must develop the sophistication to advance its interests through multiple strategic partnerships. This means building deep Asia competence while leveraging our natural advantages in energy and resources.

Most importantly, it means adapting for our purposes the strategic approach of countries like India: seeking convergence where interests align, while maintaining our autonomy through diversified relationships and clear-eyed pursuit of national interests.

Stewart Beck is the former President and CEO of the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. His diplomatic career included appointments as Canada’s High Commissioner to India, Consul General to Shanghai, and postings in Taiwan.

Carlo Dade is the Director of International Policy at the School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary, prior to this he was Director of the Centre for Trade and Trade Infrastructure at the Canada West Foundation.