Canada’s Soft Landing: Inflation Down, Interest Rates Falling, Economy Growing

Kevin Page with Lilas Forcade

October 24, 2024

On October 22, 2024, the Bank of Canada reduced its policy interest rate by 50 basis points to 3.75 per cent, down from a 5 per cent peak in June 2023. Further reductions in the policy rate, as well as household and business interest rates, are anticipated in the months ahead. Statistics Canada’s latest releases for inflation and output tell the remarkable story of Canada’s economic soft landing. The postscript is unwritten.

The soft-landing story is full of twists and turns that have kept political leaders and policymakers on edge for nearly five years. It is both a Canadian and global story, reflecting historic events (e.g. COVID pandemic; Russian invasion of Ukraine, supply-chain kinks) and policy responses coordinated with international institutions.

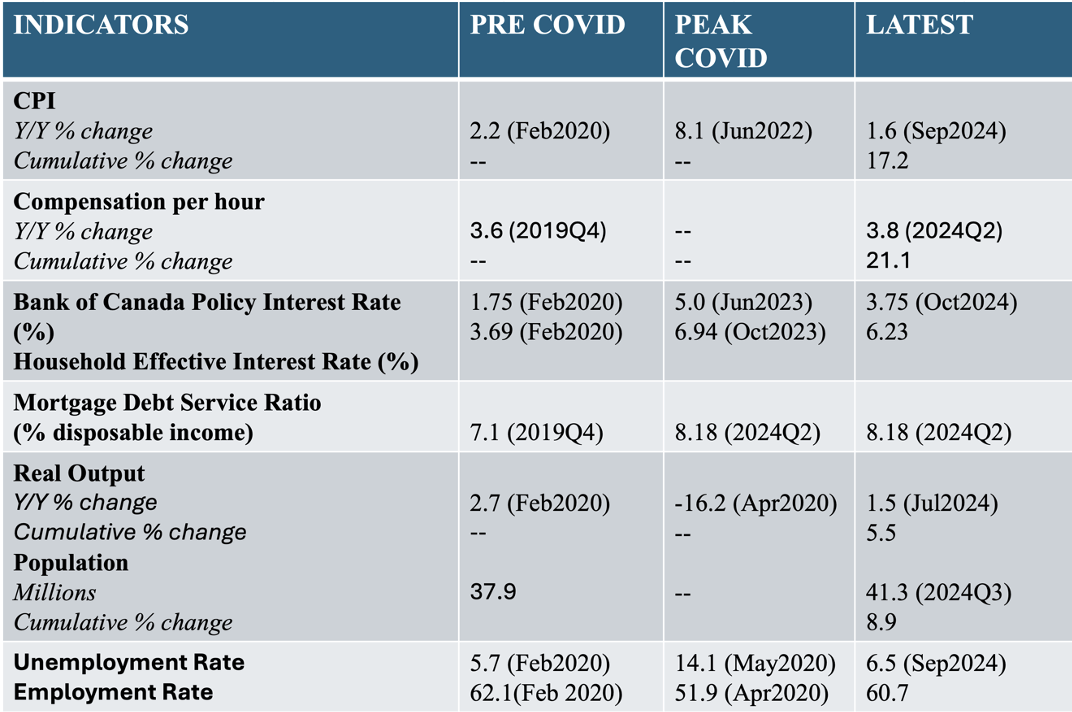

Table 1

Hard Facts on Canada’s Soft-Landing

Source: Statistics Canada; Haver Analytics

Source: Statistics Canada; Haver Analytics

The recent ups and downs of the Canadian economy are unprecedented in modern times (Table 1). The amplitude of the swings exceed those experienced under Pierre Trudeau in the early 1980s or Stephen Harper during the 2008 global financial crisis.

The CPI rate of inflation went from 2.2 per cent in the pre-COVID period to a high of 8.1 per cent in the summer of 2023, to the current rate of 1.6 per cent. Over a similar period, the Bank of Canada policy interest rate rose from 25 basis points to 5 per cent (a modern high at record pace) and has subsequently fallen to 3.75 per cent. Real output was growing at 2.7 per cent before COVID. During the lockdown, it fell a record 16.2 per cent in April 2020 on a year-over-year basis.. The latest release from Statistics Canada has real output up 1.5 per cent.

In economic parlance a soft landing denotes a significant reduction in the inflation rate through monetary policy tightening (i.e., increases in the policy interest rate) and fiscal policy discipline (i.e., holding the line of the size of budgetary deficits) without triggering a serious decline in economic output (i.e., an economic recession).

Is it time to declare “mission accomplished” on Canada’s soft landing?

Or, to quote Winston Churchill after the second battle of El-Alamein in 1942, is it, perhaps, “the end of the beginning”?

Ironically, both perspectives are apropos. The soft-landing journey from an economic indicator perspective is largely accomplished. This is an historic macroeconomic achievement for central bankers like Tiff Macklem and finance ministers like Chrystia Freeland. Thank you.

On the other hand, the aftermath policy environment remains challenging. Consumer and business confidence has been impaired by the economic roller coaster. Financial vulnerabilities continue with challenges related to affordability, housing and elevated debt. Electorates do not favour incumbent governments. Populism is on the rise. It may be years before Macklem and Freeland receive wider gratitude. When it comes, it will likely be from economic historians.

How we find our way through the postscript of the soft-landing story may depend more directly on political dynamics (the impact of populism on policy and institutions) than economics.

The dissatisfied feeling held by many consumers and businesses is imbedded in numbers. Table 1 shows that inflation is up more than 17 per cent cumulatively since the start of COVID in early 2020. That is a lot for households accustomed to prices increasing an average of 2 per cent a year. Real output is up 5.5 per cent since the start of COVID. While the economic pie is growing (good), the slices of the pie have gotten smaller (not good). Population growth has exceeded real output growth.

Slow growth and high interest rates are not a good environment for business investment. This hurts productivity and future standards of living. Record high debt-service ratios on mortgages and an unemployment rate that has drifted upward to 6.5 per cent, well above pre-COVID levels, will not create a party mood around a soft-landing policy victory. Incumbent governments beware.

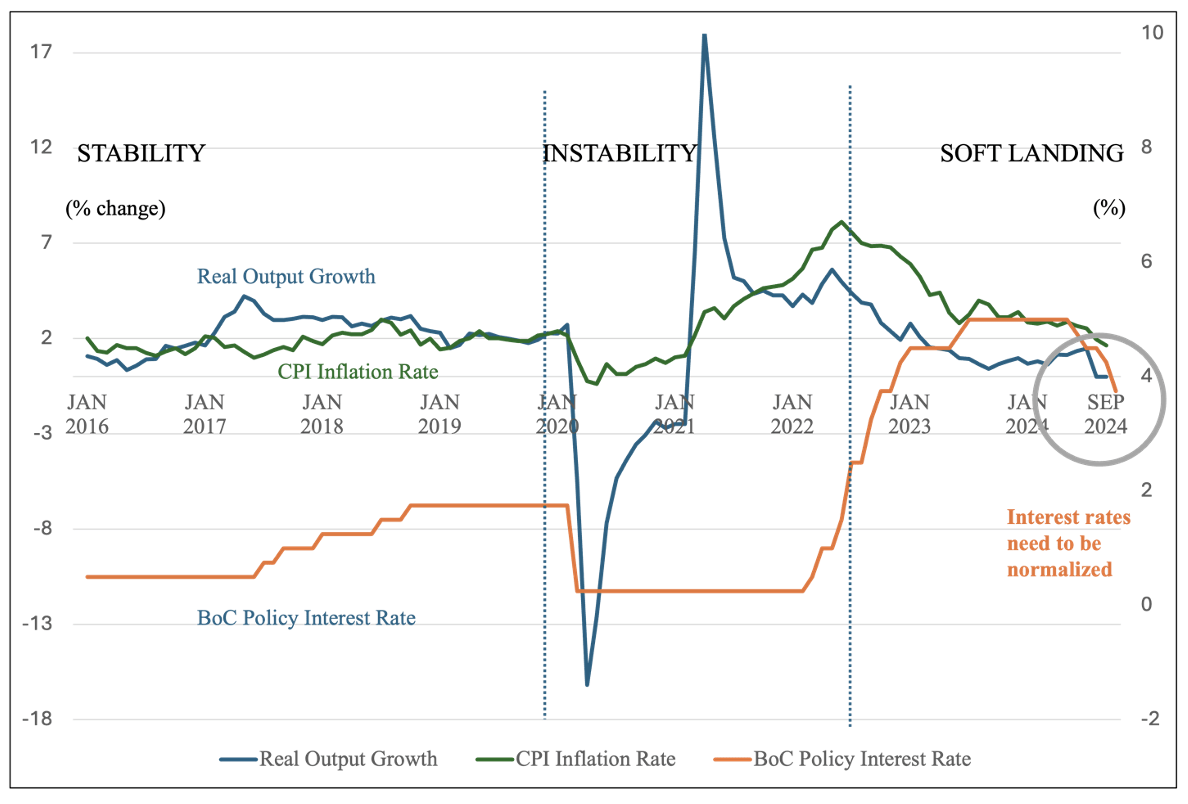

Chart 1

Tale of Differing Economic Periods: Macro-Stability to Instability to Soft Landing

Source: Statistics Canada; Haver Analytics

Source: Statistics Canada; Haver Analytics

Chart 1 shows what a soft-landing looks like. From a macro-policy perspective, it is equivalent to landing a plane on an aircraft carrier with turbulence.

The Liberal government has already presided over three economic periods – relative macro stability (2015 to 2019) to historic instability (2020 to 2024) to soft-landing (2024). Barring unanticipated events (merde happens), further reductions in interest rates will boost growth in 2025. Will the Liberal government have the benefit of another period of relative economic stability – however short – before the next election? Time will tell. The opposition parties are poised for an election. Prime Minister Trudeau is struggling to maintain party leadership.

Chart 1 shows why the Bank of Canada was criticized for a slow policy response. With ongoing debates about factors that were pushing inflation upwards in 2021, the Bank of Canada started late in increasing policy interest rates. With inflation now comfortably in the target range of 1 to 3 per cent, the larger (50 basis point) reduction in the policy rate on October 22, 2024 suggests they want to avoid a mistake on normalizing the rate (2 to 3 per cent) in the face of a weak economy.

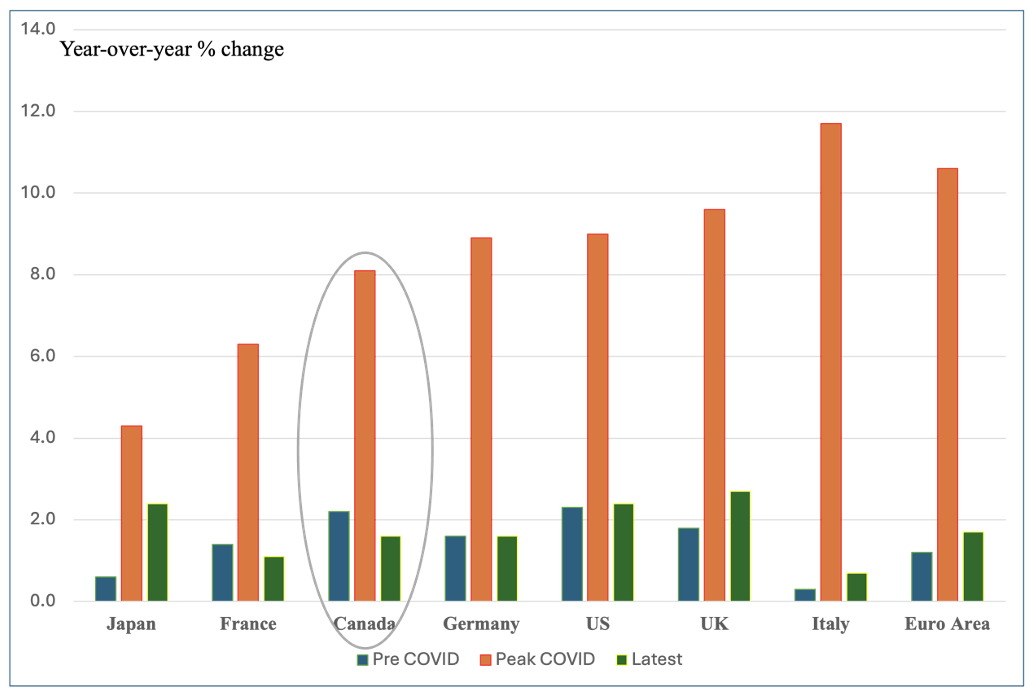

Chart 2

CPI Rate of Inflation: Comparison with G7 and Euro Area

Source: Statistics Canada; Haver Analytics

Source: Statistics Canada; Haver Analytics

Chart 3

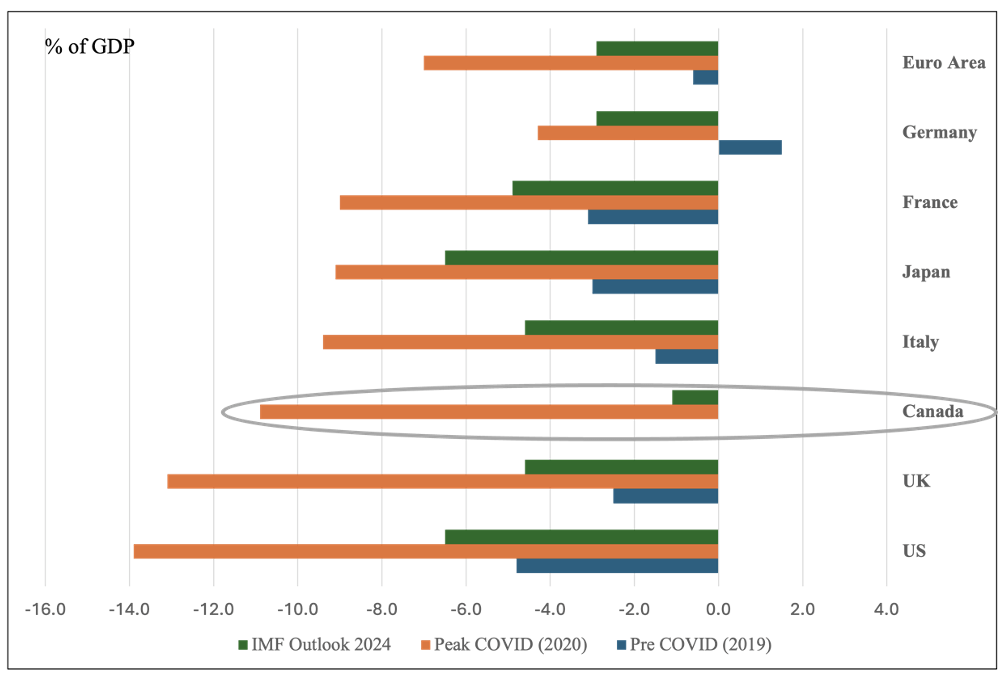

General Government Budgetary Balance Comparison with G7 and Euro Area

Note: The general government balance for Canada was zero (in-balance) in 2019. It includes central and sub-national governments. Source: IMF Fiscal Monitor

Much has been made by political opposition parties in Canada of the notion that macro-fiscal policymaking in Canada has underperformed since the start of COVID. It is not true.

Chart 2 illustrates that Canada’s inflation rate experience was very similar to other G7 economies, and notably better than the average Euro-area experience, which took a more direct impact from rising oil prices in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Chart 3 illustrates Canada’s general government budgetary balance (federal-provincial-local) relative to GDP, estimated by the IMF to be the lowest in the G7 in 2024 and much better than the average in the Euro area. This reflects the relatively quick unwinding of COVID-related fiscal supports. All governments of advanced economies are facing higher debt loads.

The return of better and more stable macro policy fundamentals (i.e., inflation, interest rates) creates an opportunity for a policy shift that focuses more on sustainable growth.

The challenge for the Bank of Canada will be to continue the timely path to normalization of the policy interest rate (2 to 3 per cent) while anchoring inflation expectations around the 2 per cent target. This policy path will take place in an environment of sluggish growth stemming in part from the continuing impact of high real (after inflation) interest rates on consumption and investment and high economic uncertainty from geopolitical conflict.

The challenge for the federal government will be to work with the private sector to strengthen innovation and productivity and support cleaner energy transition while maintaining fiscal discipline to restore fiscal buffers. This pivot must take place in an environment where confidence is weak and democratic institutions around the world are being challenged. The stakes are high.

Lilas Forcade is a fourth-year economics student at the University of Ottawa.

Kevin Page is the President of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa, former Parliamentary Budget Officer and a contributing writer for Policy Magazine.