Canada’s Second World War

Tim Cook

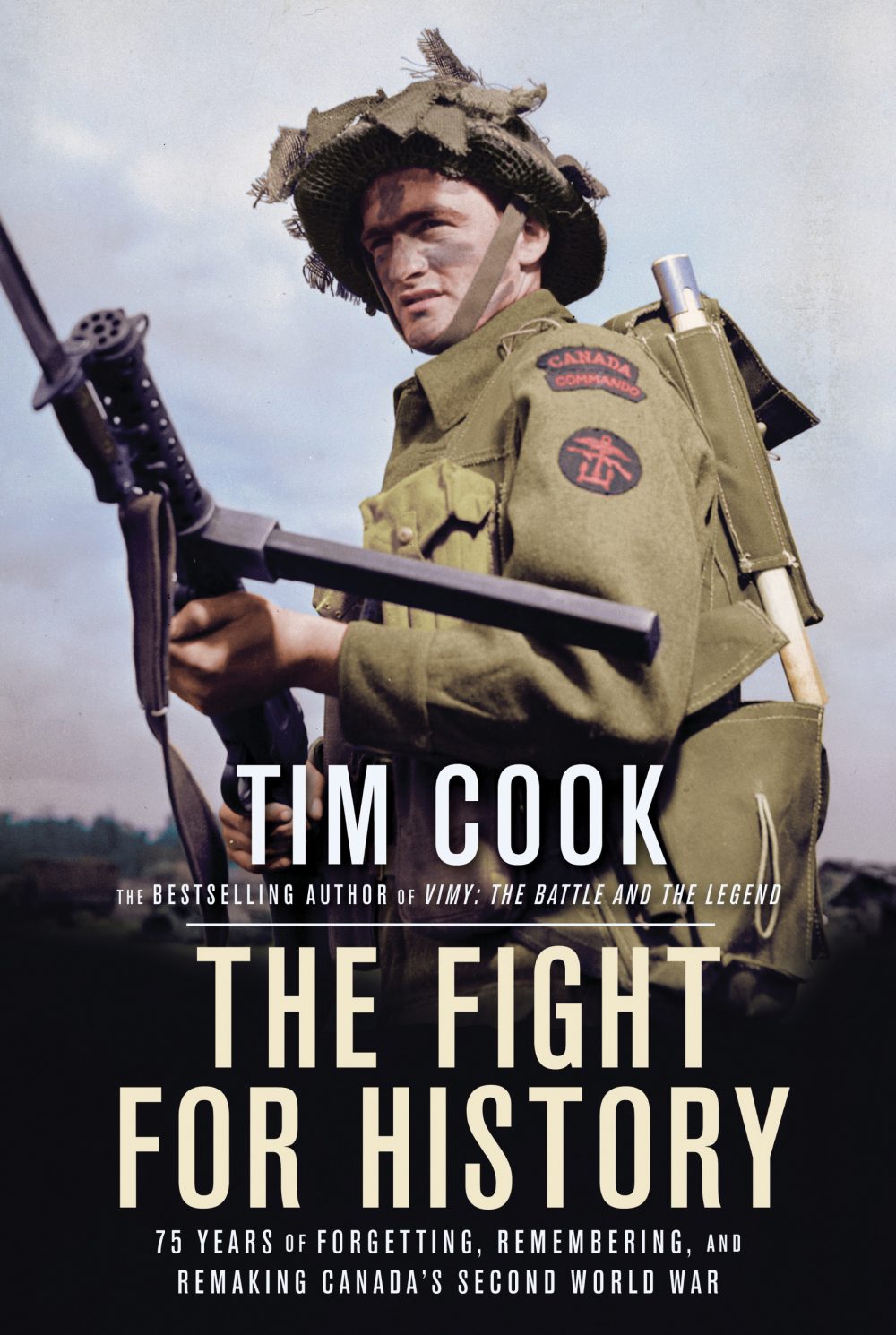

The Fight for History: 75 Years of Forgetting, Remembering and Remaking Canada’s Second World War. Toronto: Penguin Random House Canada, 2020.

Review by Anthony Wilson-Smith

“All wars,” the novelist Viet Thanh Nguyen once observed, “are fought twice—the first time on the battlefield, the second time in memory.” Then there is Canada, where our unending interest in defining our identity means we relive wars many times over. We do so with attitudes ranging from indifference to willful ignorance to periodic pride and appreciation of both our achievements and losses.

“All wars,” the novelist Viet Thanh Nguyen once observed, “are fought twice—the first time on the battlefield, the second time in memory.” Then there is Canada, where our unending interest in defining our identity means we relive wars many times over. We do so with attitudes ranging from indifference to willful ignorance to periodic pride and appreciation of both our achievements and losses.

With that in mind, the influential Canadian military historian Tim Cook, who has taken up the torch from Jack Granatstein and the late Desmond Morton as a new generation’s pre-eminent voice in the field uses the quote as a framing device in his superb new book The Fight for History: 75 years of Forgetting, Remembering and Remaking Canada’s Second World War. As Cook notes, our relationship with our country’s role in the Second World War is “complicated, complex and ever-shifting.” That attitude is quite different from other Allied partners who fought the war to its bloody but successful close. In the United States, Cook writes, “the Second World War is the ‘Good War’ in which the Americans defeated their evil enemies.”

In Great Britain, ‘the dominant memory of the war is that of the lone island standing up against overwhelming Nazi forces’, even though, he notes, more than half a billion people in the then-British Empire also pitched in. In Russia, they still speak proudly of ‘The Great Patriotic War’—and a huge memorial en route from Moscow’s Sheremetyevo Airport into the city marks how close the Germans came to capturing the capital.

But here, Cook argues convincingly, Canada’s important wartime role and contributions have been largely downplayed, both by governments and the population at large. The reasons include timing, circumstance, realpolitik, societal and generational changes, and the traditional Canadian reluctance to applaud ourselves. Only in recent years, with the number of Second World War veterans dwindling, have we started to acknowledge the enormity of their achievements and sacrifices.

The numbers give a powerful sense of the commitment of Canadians. When the Second World War began in 1939, Canada was a country of 11 million people. By 1945, 45,000 Canadians had been killed and 55,000 wounded. An untold number suffered from trauma that meant their lives and those of their families were never what they would have been. In the 1950s, one in three adult males were war veterans, along with 50,000 women. Canadian casualties are buried in 70 countries around the world.

Despite that, successive generations of Canadians, including, sometimes, participants, often found it convenient to push war memories aside. Cook quotes an editorial from the time in The Regina Leader-Post on the returning soldiers: “The long trail which stretches behind them is strewn with memories, and the road ahead shines bright with hope.” By the 1950s, veterans and others were raising families at an unprecedented rate, and focused accordingly. The 1960s brought huge social change; anti-war sentiments, fed by the United States’ troubled engagement in Viet Nam, were also felt in Canada.

By the 1970s, interest in November 11—Remembrance Day—was so low that Brig. Willis Moogk lamented that many Canadians looked on it “as just another holiday, rather than a day of grateful and thoughtful remembrance.” By the 1980s, Second World War veterans, now in their 60s, were shuffling off centre stage. A 40th anniversary event in Normandy, France, commemorating the historic D-Day invasion, was notable for the low level of Canadian engagement.

By the early 1990s, teaching of Canada’s role in the war was near-absent from many schools, and what was available in the media focused inordinately on the occasional mistakes and failings of Canada’s military rather than its accomplishments. Cook focuses particularly on the three-part CBC series, The Valour and the Horror, which was harshly critical of Allied Bomber Command—including the Royal Canadian Air Force—as well as some decisions made during the D-Day invasion. A CBC review subsequently concluded that the series “is flawed and fails to measure up to CBC’s demanding policies and standards”, so would not be re-broadcast. As well, Cook delivers a frank account of the many pressures and controversies surrounding the building of a new Canadian War Museum, which has since surmounted those and become a great success.

Those controversies marked a turning point. At the 50th anniversary of D-Day in Normandy in 1994, Prime Minister Jean Chrétien led a large delegation in ceremonies aired on all national networks and watched by millions of Canadians. (As a journalist covering the event, I recall seeing Chrétien, long after other dignitaries had returned to their hotels, chatting informally for more than an hour in the darkened cemetery with remaining veterans.)

In making his case, Cook’s many strengths are again evident. He writes fluidly, with a sharp eye for detail and the telling anecdote. His sympathies are with people on the ground rather than higher-ups—but he has a keen understanding of politics and how and why decisions are made. He highlights the complex challenges of war—for example, the anguished decision celebrated naval commander Harry deWolfe made when, after rescuing some men from a sinking vessel, had to abandon others to their death in order to escape nearby U-Boats. His descriptions of the mental challenges that soldiers faced after the war, drawn from letters, are heartbreaking.

And now, 2020 almost certainly marks the last major anniversary—the 75th anniversary of the end of the war—for which we will still have survivors with us to mark the occasion. We do so, as Cook laments, still “without a major, unifying Second World War memorial”—again unlike our Allies. In that absence, it becomes particularly important to remember the people who live among us still touched by the war’s direct hand. That includes not only the veterans, but surviving widows who lost husbands, the war-era children now grown old with scant memory of their fathers, and the ravaged small communities that lost the young people who would have forged their futures. After years of neglect, Cook concludes, the Second World War “has been waiting for us to return to it.” As he explains so eloquently, it’s an invitation we need to accept.

Contributing Writer Anthony Wilson-Smith is President and CEO of Historica Canada.