Canada’s Role in a World of Turmoil

After the end of the Second World War in 1945 and following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, Canada played an important middle power role in the post-war and post-Cold War spread of democratic values and free market economies. But that’s not the shape or direction of today’s emerging world of turbulence. Our lead foreign affairs writer Jeremy Kinsman asks the pertinent Canadian question: what is Canada’s role in this new world of turmoil?

Jeremy Kinsman

March 4, 2020

After 75 years, our foreign policy belief system, the mantra of cooperative liberal internationalism, is being challenged, especially in our own neighbourhood.

A contagion of competitive nationalistic illiberalism and misremembered nostalgia is pushing back against the forces of globalization and change. Borne on the winds of populist slogans—“Make America Great Again,” or (Brexit’s) “Take Back Control”—it venerates old identities, status, and values.

Change happens. Its impact on world rankings has created an increasingly fierce U.S. resistance to China’s challenge to U.S. primacy, catching Canada in the middle.

Confidence and turbulent change have always interacted in contrary global cycles.

Upheaval in the 1970s had left many older Americans reeling, and longing for times gone by. Ed Koch, the ebullient mayor of New York, continuously checked their pulse asking, “How am I doing?”

One day an older lady pleaded, “Mayor! Please make it like it was…Make it like it used to be.”

“Lady,” he said, “It was never as good as we think it was…But I’ll try.”

Of course,today’s turmoil roiling the world shows a drastic change in mood from the internationalist optimism that accompanied the Berlin Wall’s fall in 1989. That ignited a decade when we assumed more open and cooperative societies would be de rigueur. It seemed inevitable that national impulses and expectations would be mediated through universal cooperative international rules and institutions.

So it goes. Our national interest is as vested as ever in cooperative rules-based internationalism, but we can’t hang on to old international institutions, habits of thought, and world rankings that are overtaken by

new realities.

But we are stuck with our geography. Still, we needn’t bow to Montesquieu’s dictum that geography is all that drives our fate. It’s also

our leverage.

We shall always be emphatically North American, though our geographic self-concept is enlarging as we add our sense of our North, as in “From Sea to Sea to Sea.”

Canada’s outward view is thematically very different from that of the Trump White House. We need to stay unapologetically globalists, and continue energetically to strengthen ties with like-minded internationalists as “the other North America.” We need to work together to reboot the world’s belief in liberal internationalism.

It’s worth reflecting on how it lost ground.

It happened the way Hemingway described in The Sun Also Rises, how bankruptcy happens: at first, “gradually. Then suddenly.”

The nineties had a golden surface. Western stock markets boomed, propelled by new tech. China and India began their accelerated ascension to the world Premier Economic League, lifting hundreds of millions into the middle class.

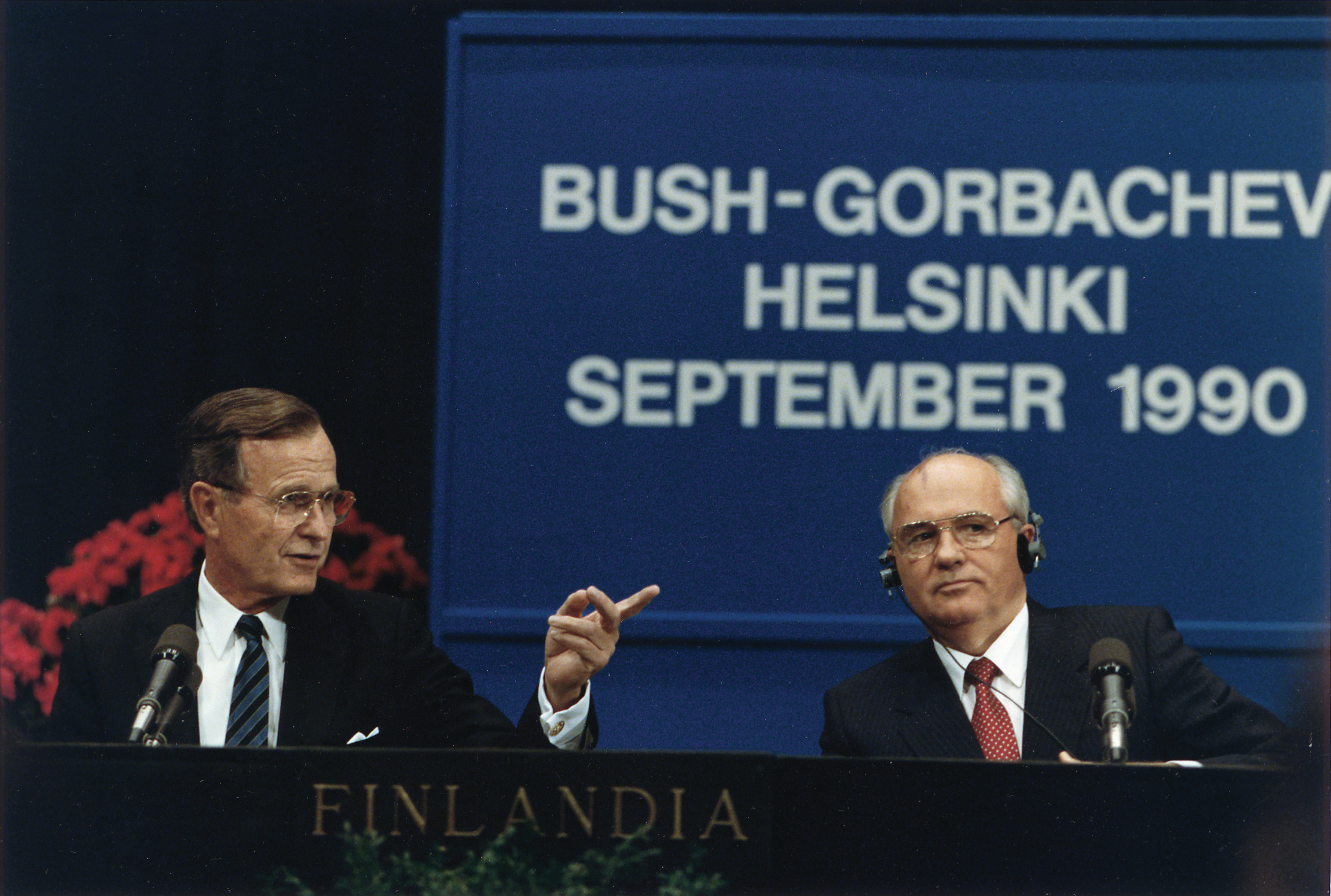

We celebrated the end of the Cold War, an outcome enabled by Mikhail Gorbachev. But we were naive to think that it was bound to be welcomed as win-win for everybody. Despite George H.W. Bush’s thoughtful advice, American triumphalism began to make resentful Russians feel like losers. U.S. neo-conservatives dismissed grievance over NATO expansion to Russia’s borders. “We won. Get over it.” So, Vladimir Putin’s recovering Russia went rogue.

On 9/11, 2001, the roof fell in on complacent Western narcissism. Jihadist terrorism became a new global scourge. Borders hardened, including our own with the U.S. Societies re-prioritized for a new kind of war.

Unfortunately, in 2003, the U.S. and U.K. rushed to an unnecessary invasion of Iraq that catastrophically turned the Middle East into the world’s first failed region. Jean Chrétien made the right call, to stay out of what presidential candidate Barack Obama would later term “this stupid war.”

In 2008, the evidence of endemic financial fraud in Western financial services devastated the reputation of the capitalist system in the eyes of millions. But again, Canadians defied the crisis. Our prudent financial regulations kept us on dry land from the flood of bankruptcies that affected ordinary people almost everywhere else.

Obama won office just as the still underestimated 2008 financial crisis was unfolding. His distinct preference for multilateralism renewed the hopes of internationalists. Moreover, his belief that “yes, we can,” helped to fuel the Arab Spring of protests and uprisings against authoritarian governments in the Islamic world.

Except for Tunisia’s, they failed.

Moreover, while Canada embraced Obama’s internationalism, democracy-averse China and Russia, even India, chose to pump up nationalist pride and purpose. To some extent, they gamed the international economic system which they regarded as serving the interests of the established economic powers who designed it. The World Trade Organization staggered into increasing irrelevance.

Rising countries resented the assumption they should just imitate Western liberal ways. On the other hand, many of the best and brightest in the post-communist countries of Europe emigrated to the West. This depletion by emigration induced phobic antipathy to phantom immigration, especially Muslim, as the grotesque Syrian civil war and conflict with ISIS spewed millions of refugees across porous European borders (though paradoxically, not to the post-communist countries in question).

Populist nationalist leaders exploited the fever of resentment, contesting liberal Western values. Demagogues marshalled nationalist, ethnic, and sectarian majorities against pluralism, change, and established “elites” at home and abroad. They also began to disassemble the checks and balances of democracy in favour of authoritarian power. The contagion of nationalist populism metastasized to Western democracies where “left-behind” workers blamed “globalization” and the remorseless energy of change for the export of their jobs and the hollowing-out of their communities.

Amplified by errant and irresponsible monetized social media, political polarization eviscerated the centre, where compromise can live. As William Butler Yeats put it in The Second Coming a century ago,

“Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold. ……..

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.”

Thus, “America First!” became a winning presidential slogan in 2016, supplanting Obama’s internationalist leadership. Tariffs and sanctions were weaponized against partners who resisted the systematic undoing of international agreements to tame humanity’s greatest threats, nuclear weapons, and global warming.

First gradually, then suddenly, internationalist Canada was mugged by the increasingly dominant nationalist reality. Yet, we managed a defensive save of our most important relationship by negotiating an upgrade of NAFTA. We completed a comprehensive 21st century economic cooperation agreement with the EU. But with the other of the three great economic powers, China, it went sour.

The emerging U.S./China rivalry blindsided us into entrapping Huawei’s Meng Wanzhou at YVR on behalf of a vindictive U.S. Department of Justice. The U.S. sought to hobble China’s principal competitor for global telecommunications primacy with an indictment for Iranian sanctions-busting that had nothing to do with Canada.

This isn’t the place to re-litigate the argument that Meng Wanzhou certainly did not commit a crime that would merit at least a year’s imprisonment in Canada that the extradition treaty stipulates for extradition. Yet, for decades, Canada has opposed the extraterritorial application of U.S. law to foreigners, and abroad. It is baffling why Canadian Justice officials who, according to the treaty, represent the U.S. case in Vancouver court hearings continue to present over-the-top arguments that Canada should extradite the ambushed Huawei executive.

In a cynical and deplorable reprisal, the furious Chinese jailed two innocent Canadians. It was a very harsh warning to all and sundry that China has real red lines at stake in this new era of all-out competition with the U.S. Unfortunately, it prompted a phobic wave of anti-Chinese reporting in Canadian print media, and calls for counter-reprisals against the Chinese. We resisted those, but clearly, the rosy lens which for some time had blurred the real nature of new China’s old-style communist leadership needed an updated prescription. With wary eyes wide open, we need that relationship.

China’s profound crisis over the coronavirus epidemic has been a chastening experience, jarring their enormously successful top-down national development narrative. But it has permitted Canadian and Chinese officials to connect and cooperate. It may have increased mutual confidence so that we can resolve our shared hostage problem.

Meanwhile, the old U.S. neo-conservative security blob is pumping up the necessity of a new Cold War against China, along with hard-line solidarity against other enemies, notably Russia, and Iran. Hopefully, the Trudeau government will keep its composure and accept that we have to navigate the world on terms that suit our interests. Lining up behind the Trump administration in an adversarial G-2 contest is not the way to go.

Trump’s ascent wasn’t an accident. America today is what it is, polarized, dysfunctional, and unreliable at the top. As Lester Pearson once said, we shouldn’t shy from giving the Americans a kick in the shins every so often. Our Canada-U.S. working levels function day-to-day pretty well in mutual interest. Basic friendships endure and sooner or later will again prevail in defining the bilateral relationship.

In the meantime, our national interests call for determined defence of international cooperation, and resistance to nationalist populism. The most effective promotion of democracy is by the vivid example of inclusive and responsive governance at home that works. The crisis over the Wet’suwet’en territory is a test. Resilience and capacity to navigate deftly challenging surprise “events” like the Iranian plane catastrophe and our breakdown with China

also test us.

There will always be combative Canadian political voices condemning a smile for the Iranian or Chinese foreign minister as inappropriate, who judge that reaching out to communicate is a sign of weakness.

But it never is.

Contributing Writer Jeremy Kinsman is a former Canadian Ambassador to Russia and the European Union, and High Commissioner to the U.K. He is a Distinguished Fellow with the Canadian International Council.