Canada’s Road to Net Zero–A $2 Trillion Clean Energy Transition

Canada has a math problem. When it comes to greenhouse gases, our numbers don’t add up. For 25 years, we’ve fallen short of major environmental goals, and stand to miss future climate commitments if we don’t take a new approach to policy and finance. The climate crisis presents an opportunity for a generational shift in industrial policies, along with federal-provincial-Indigenous cooperation, to lay the course for investments and regulatory rules that can help a range of strategic projects and initiatives transcend political cycles over the next 25 years and encourage the mobilization of $2 trillion, largely from private sources, to finance Canada’s energy transition.

John Stackhouse

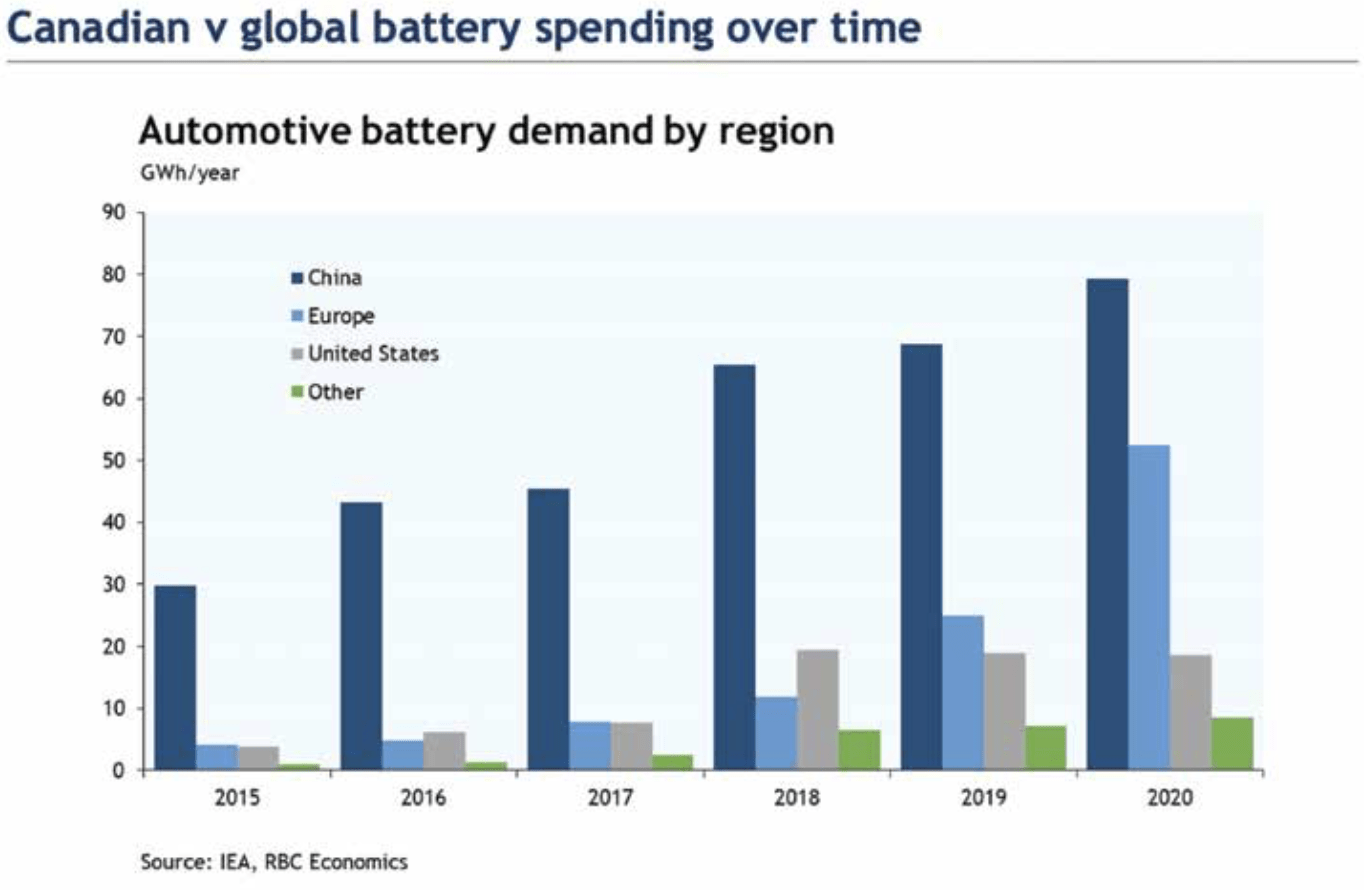

At the height of the Glasgow climate conference, Canada joined a coalition of countries, cities and corporations signing a declaration to end the sale of new internal combustion engine vehicles by 2035 in advanced economies and 2040 elsewhere. It was an important signal to the auto industry, as well as to government planners and consumers, and a critical milestone on our road to net zero.

Back home, in the birthplace of Canada’s automotive industry, a different signal was rolling off the assembly line. On the same day as the Zero Emissions Vehicle Pledge was signed, GM Canada began producing a new line of Chevy Silverado, its best-selling pickup truck, at its retooled plant in Oshawa, Ontario. GM, which had joined Canada and others in signing the Glasgow EV pledge, said it was responding to consumer demand. With the support of the federal and provincial governments, the company was also helping recharge Ontario’s manufacturing sector, and position the province for the next generation of vehicles.

Was it a case of crossed wires, or a booster cable for the energy transition? Either way, the pick-up paradox is just one challenge awaiting the new federal government as it gets down to the tough work of planning and budgeting a more ambitious climate agenda.

Was it a case of crossed wires, or a booster cable for the energy transition? Either way, the pick-up paradox is just one challenge awaiting the new federal government as it gets down to the tough work of planning and budgeting a more ambitious climate agenda.

On current course, Canada will be challenged to meet our 2030 targets for greenhouse gas emissions. Some of the policies in place, including carbon pricing, methane regulations and an expected clean fuel standard, will help close the gap. But across pretty much every sector, we’re not on pace to get to net zero, and need to rapidly shift capital spending to transformative technologies and scale them for consumer use.

The shift is about more than waiting for the arrival of a Silverado EV, which is indeed in the works and slated for production in 2023. It’s about a massive shift in capital flows for companies that can power the transition much faster than government policy can on its own.

Research by RBC Economics and Thought Leadership estimates Canada will need to mobilize $60-80 billion a year, mostly from private sources, to get the economy to carbon neutrality. That’s roughly four times what we spend now on climate action — and even that won’t be enough to get us all the way to net zero by 2050. We’ll have to rely on technologies that have yet to be proven, and nudge more consumer behaviour change than we’ve seen to date.

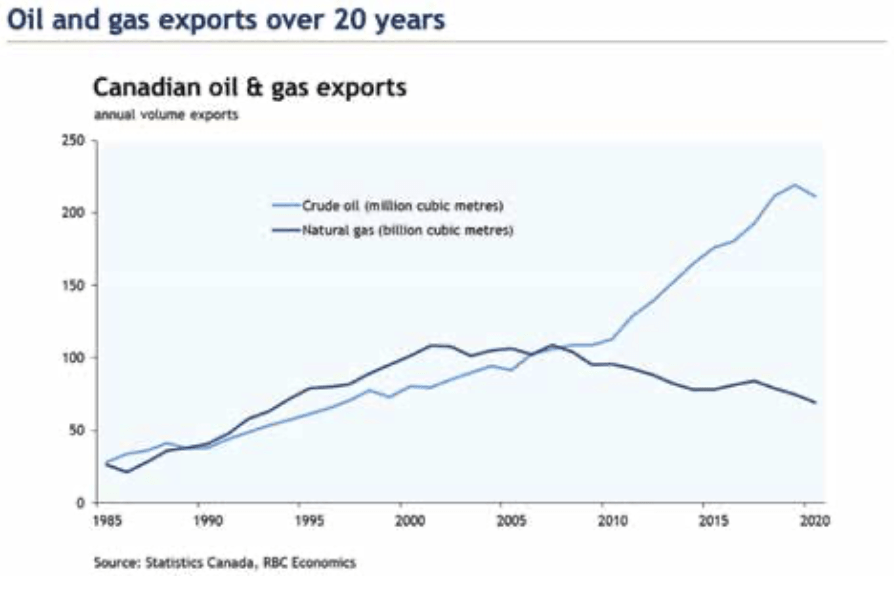

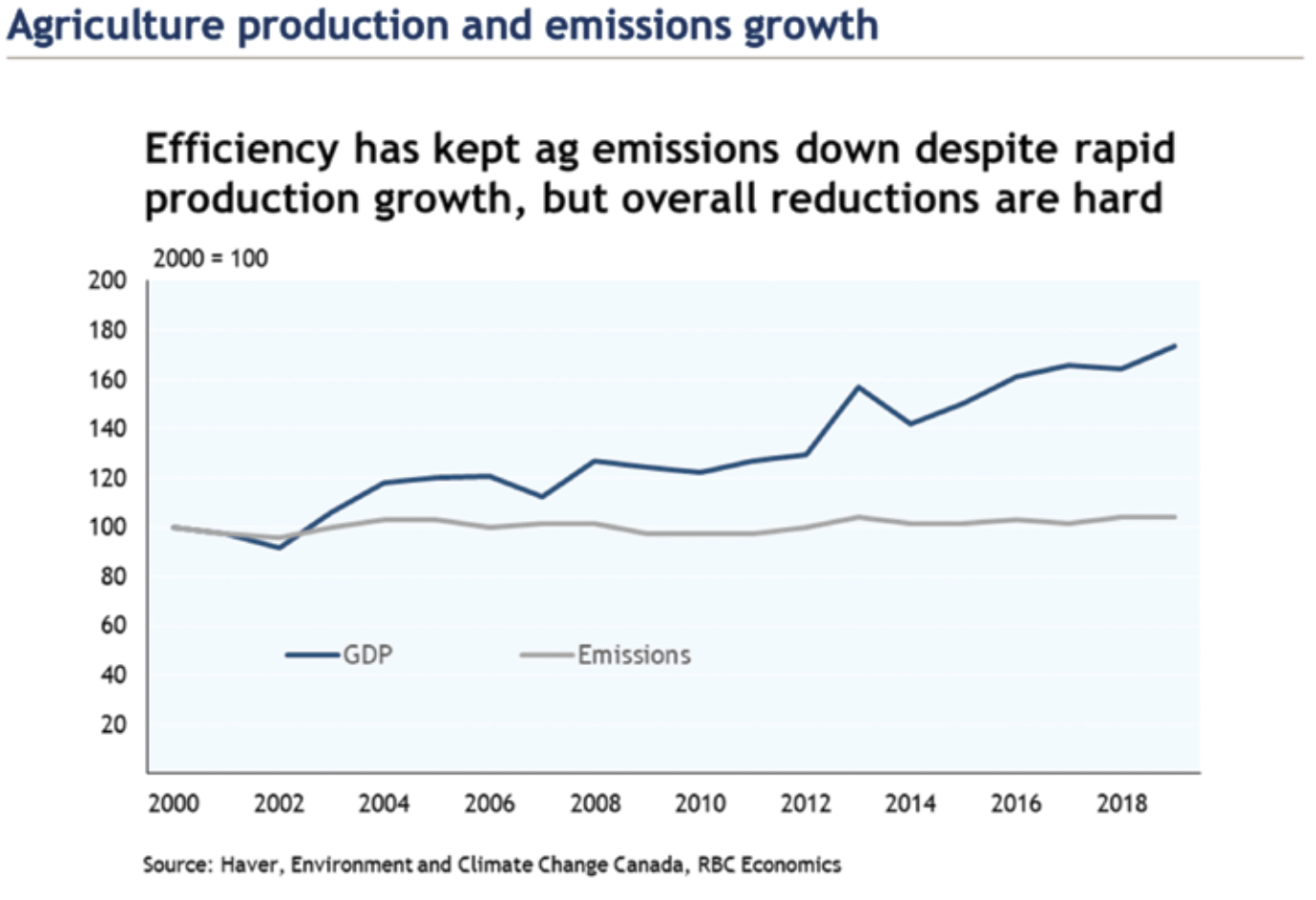

Critically, Canada will require a more coherent and cohesive national plan. RBC’s $2 Trillion Transition report lays out six pathways to deploy climate capital over the next 25 years — in electricity, oil and gas, heavy industry, buildings, transportation and agriculture. This includes tens of billions of dollars for abatement technologies, such as carbon capture and sequestration, to capture emissions from our heaviest emitters at source, before they enter the atmosphere. We’ll need even more capital to double electricity production — including more hydro and nuclear power — for a rewired economy. And Canada’s farmers, tens of thousands of them, will need to invest in regenerative processes and methane capture technologies to cut their net emissions and place Canada among the leading sources of sustainably produced food.

Critically, Canada will require a more coherent and cohesive national plan. RBC’s $2 Trillion Transition report lays out six pathways to deploy climate capital over the next 25 years — in electricity, oil and gas, heavy industry, buildings, transportation and agriculture. This includes tens of billions of dollars for abatement technologies, such as carbon capture and sequestration, to capture emissions from our heaviest emitters at source, before they enter the atmosphere. We’ll need even more capital to double electricity production — including more hydro and nuclear power — for a rewired economy. And Canada’s farmers, tens of thousands of them, will need to invest in regenerative processes and methane capture technologies to cut their net emissions and place Canada among the leading sources of sustainably produced food.

Properly planned and deployed, this new approach to sustainable capital could lift Canada above our decades-long trend of low economic growth, and help businesses become more competitive globally. Placed in the hands of climate entrepreneurs and business innovators, it could attract and retain a generation of talent to Canada, too, through immigration, higher education and skills training.

The technologies and capital for much of this transition are already available. But they’re not in place for two key reasons: market failure and policy failure.

First, the market failure. As vehicles have become more fuel efficient, we’ve bought more and driven more, which has pushed overall vehicle emissions up rather than down. In Ontario, vehicle emissions are 50 percent above 1990 levels, and may soon overtake the oil sands as a source of greenhouse gases, given the province’s population growth and urban design.

Similar consequences of population and economic growth can be found in the housing sector. We’re not only building more houses as a country, for good reason. As those homes become more fuel efficient, we’re building larger ones, without enough focus on regional and local energy systems. The market is not allocating resources efficiently.

As for policy failure, we’re falling short of our climate goals because they’ve not been accompanied by roadmaps or accountabilities. The COP26 Glasgow conference generated several important commitments, including on methane, coal, forests and vehicles, but as is often the case with summits, delegates went home with more promises than plans.

As for policy failure, we’re falling short of our climate goals because they’ve not been accompanied by roadmaps or accountabilities. The COP26 Glasgow conference generated several important commitments, including on methane, coal, forests and vehicles, but as is often the case with summits, delegates went home with more promises than plans.

If we’re to get a different result, we need a plan and a playbook to blend public, private and Indigenous capital, and create more harmony in federal, provincial and local policies.

The capital is largely there. Glasgow included historic commitments from the world’s financial sector, including Canada’s major banks, insurance companies and pension plans that collectively have the balance sheets to get Canada to net zero — and improve Canada’s economic performance. The conference also strengthened our collective approach to sustainable finance, through tools such as emissions trading, emissions disclosure and taxonomies (or classification systems) that give lenders and investors the ability to move capital, efficiently and transparently, to transition activities.

In Canada’s case, we’ll need to invest at least $500 billion by the end of the decade in carbon capture pipelines, hydrogen hubs, electricity grids, neighbourhood heating systems and charging networks, among other needs. And that means developing project plans and regulatory frameworks, and strengthening our approach to sustainable finance, within the next 36 months.

Bottom line: If capital is not allocated to these initiatives by 2025, they won’t be working by 2030.

Fortunately, Canadians have amassed enormous savings through the pandemic, and for much longer through world-class pension systems. As we look for a more economically sustainable recovery, with much less government debt, we can harness those savings (as well as global capital) to help finance the transition, and finance Canadian retirements.

New financing frameworks developed around Glasgow, including the Net Zero Banking Alliance, will enable banks, pension funds and insurers, among others, to better track and report on the emissions related to financing activities, and to demonstrate progress. It would be dangerous, and even undemocratic, to expect the financial sector to dictate or regulate the path to net zero. But financial flows and returns can be a useful barometer for the country to measure and monitor progress, and continue to look for ways to optimize the allocation of capital.

The money, though, won’t flow on its own. Canadians need to compete for the trillions of dollars that Mark Carney spoke about in Glasgow, and that will require a much greater focus on economic returns as well as climate impact. They can co-exist, which is why green capital is flowing to Europe, the United States and China.

The money, though, won’t flow on its own. Canadians need to compete for the trillions of dollars that Mark Carney spoke about in Glasgow, and that will require a much greater focus on economic returns as well as climate impact. They can co-exist, which is why green capital is flowing to Europe, the United States and China.

To catch up, we need far more investable projects, with market rates of return, than we’re currently developing. That will require a transformation of project planning, approval and execution, which may not be easy for a pandemic-weary public. Energy shocks this fall have rattled political confidence in Europe and North America, and will be tested anew in elections in 2022 in France, the United States and elsewhere.

If others struggle to find their climate balance, Canada may have a competitive moment to gain a capital advantage, and fund breakthrough investments. But to do that, we need to consider a new playbook, including:

- a national declaration of strategic priorities like carbon capture and sequestration;

- fast-track approvals and regulatory certainty for projects deemed to be essential to net zero goals;

- sector goals for emissions, with responsibility for industry to reach them;

- new platforms and regulations for blended, long-term capital from federal, provincial, Indigenous and private sources;

- revenue models, including carbon pricing, to secure long-term cash flow for projects;

- clear emissions mandates, and deadlines, for vehicles and buildings;

- a national policy, and investment framework, to double electricity generation and distribution;

- a Canada-US policy framework for energy production and distribution, including oil and gas emissions, cross-border electricity sales and supply chains for renewable energy equipment.

Critical to Canada’s evolving climate plan will be a more disciplined approach to staging and sequencing these policies and projects. All of the above can’t be done at the same time, and none of it can be done by markets or governments on their own. We can’t do this in isolation, either, especially from the United States.

The road to net zero will not be straight or smooth. But with a reliable roadmap and a good route plan, we can still control our destination, if we get moving now.

John Stackhouse is Senior Vice President in the Office of the CEO, Royal Bank of Canada. He oversees RBC’s Economics and Thought Leadership group, co-chairs the bank’s Climate Strategy Steering Committee and is a member of the federal Sustainable Finance Action Council. He was previously editor in chief of The Globe and Mail, and editor of Report on Business, and is the author of four books, including Planet Canada: How Our Expats are Shaping the Future.