Canada’s Looming Fiscal Reckoning: Bracing for a Spending Review

The economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has rationalized unprecedented, crisis-mitigating levels of public spending. Protecting the Canadian economy from a debt crisis produced by that necessary response will require a spending review.

Helaina Gaspard, Álfrún Tryggvadóttir and Kevin Page

October 27, 2020

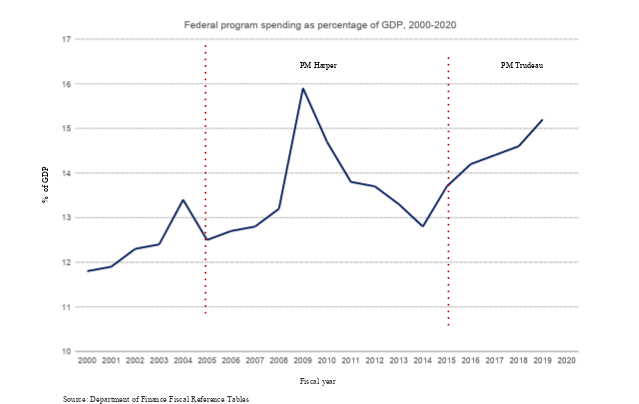

In the wake of the self-imposed economic stagnation undertaken to combat the contagion of COVID-19, Canada’s federal debt levels are projected to approach 50 percent of GDP. For perspective, before the pandemic, our debt was roughly 30 percent of GDP, down from a modern peak of over 65 percent of GDP in the mid-1990s. This 20-percent estimated increase in the federal debt-to-GDP ratio is four times greater than the 5- percentage point increase Canada experienced in the 2008-09 global financial crisis. Significant fiscal space has been used that will now be unavailable for the next government or next generation to face a pandemic, economic or other crisis, unless policies are put in place to restore fiscal room.

That should give taxpayers pause.

After the recessions in the 1980s, 90s and 2000s, governments of different political stripes undertook spending reviews to strengthen balance sheets. So, as we look ahead to the post-COVID-19 economic recovery, maybe the right question is not whether there will be a spending review but what kind of review will it be?

In 2007, Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s Strategic Review was designed to find savings to address rising debt levels. In 2004, Prime Minister Paul Martin wanted to find efficiencies to spend them on government priorities, maintaining a budgetary surplus. Most famously, in 1993, Prime Minister Jean Chrétien undertook Program Review with societal consensus for significant spending cuts to address a major debt problem.

Spending reviews in their various forms can be useful fiscal tools and important political ones to improve fiscal outcomes. Reviews can detect savings, identify opportunities to cut low-priority, outdated or redundant and ineffective expenditures, and can create space for new spending in high-priority areas such as health, environment and climate change. Sound fiscal management can make for astute politics.

Canada has options to frame its review exercise for long-term sustainability and better spending. Will the review be designed to achieve fiscal savings, a performance outcome or both? Will the review cover the whole of government or a specific policy area?

Most countries, when undertaking a review, look for some form of improved effectiveness and efficiency; a better insight into the impact of public spending. You may want to improve the performance of public expenditure or you may want to find savings to reallocate to other priority areas. This will likely be increasingly relevant as spending is reprioritized from low- to high-priority areas after the current crisis. Starting a spending review sooner rather than later could help to target stimulus, reallocate existing spending in more timely and impactful ways (e.g., towards green energy or a stronger social safety net), and, critically, create the fiscal space needed to address the growing stock of debt.

Reviews can detect savings, identify opportunities to cut low-priority, outdated or redundant and ineffective expenditures, and can create space for new spending in high-priority areas such as health, environment and climate change.

Reviews tend to target one of three goals: aggregate fiscal discipline; allocative efficiency or operational efficiency. Aggregate discipline-focused reviews help to create fiscal space through greater control over increases in expenditures. Allocative style reviews are designed to prioritize expenditures to align to political goals or priorities. Reviews targeting operational efficiency seek to improve the value-for-money of programs and policies and manage potential risks in their delivery.

Looking at evidence from Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) peer countries undertaking spending reviews, there are recurring factors that contribute to their success. Political ownership throughout the review process is essential. Defining clear objectives and scope of the review provides concrete terms for communicating progress and outputs. The use of performance data and linkage to existing budget processes ensures reviews cover the full decision-making cycle with accountability and transparency.

Countries that have a long experience of doing spending reviews, such as the Netherlands, adapt the process to political needs and the economic cycle so that it can respond to ongoing challenges. This is especially relevant in today’s fiscal context, in which countries will soon be forced to make tough decisions and look critically at their expenditure priorities and facilitate the reallocation of fiscal resources.

The current Liberal government, which was elected in 2015 in part on its espousal of deficit spending in contrast to the incumbent government’s hawkishness, is comfortable in promoting the role of the state. It is a government that spends. The government has been adding to the spending base (even before the pandemic). Consider, for instance, the multi-billion-dollar investment in skills and innovation in 2017 that was tacked on to an existing base that was not reviewed.

The pandemic has ballooned public spending to ease economic pain and help to meet people’s basic needs. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) recently called on developed economies to continue spending to sustain the grinding economic recovery. The messages are clear: this recovery will take time, it will be uncertain, we will come out of it, but we will have to spend.

How will the federal government invest to support economic recovery? How will those decisions be made? What will be the source(s) of the extra funds? How will the government demonstrate that informed and sensible decisions are being made? Spending may be necessary, but there will be ramifications. There are no free lunches with higher public debt. If what The Economist has dubbed the “eternal zero” of low interest rates rise, so will the cost of carrying additional debt.

Fortunately, in Canada, we have a functioning public financial management system that tracks expenditures and performance indicators. There is an architecture — whatever its flaws — that public servants and politicians can use to analyze spending trends, program designs, products and results. While most Canadians are indifferent to its existence, this architecture is essential for accountability.

Rather than waiting to confront a future fiscal challenge and not having the policy room to address the next crisis, we should be laying the groundwork for a spending review in the post-COVID-19 economic recovery to strengthen our fiscal health and ensure spending is delivering good value against evolving public priorities.

Helaina Gaspard is Director, Governance & Institutions at the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy (IFSD). Álfrún Tryggvadóttir is Senior Policy Analyst, Public Management and Budgeting, Public Governance Directorate, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Kevin Page is founding President and CEO of the IFSD.