Canada’s Debt Narrative, from Financial Crisis to Pandemic

When the public health crisis of a deadly global pandemic became an economic crisis in the absence of a vaccine, the economic worst-case scenario was always going to be about debt. Vaccines were patented, but their economic relief has been thwarted by delivery disruptions and the emergence of viral variants. As former Parliamentary Budget Officer Kevin Page and his co-authors write, the next factor to watch in what has been a Murphy’s Law fable will be interest rates.

Kevin Page, Donya Ashnaei and Elo Mamoh

We live in unusual, uncertain and unstable times.

Equity markets are strong—underpinned by expectations of vaccine distribution and continued support from central banks and government treasuries. Credit markets are strong. Household and business credit continue to grow—buoyed by low interest rates and easy access to money. Meanwhile, the goods and service economy is hurting from the pandemic. Output remains well below levels a year ago. The unemployment rate is uncomfortably close to 10 percent.

How do you connect strong equity and credit markets and a weak economy? One way is through debt and the expectations of more debt. Is this sustainable? No.

Will there be a soft or hard landing for economies when the music stops? The music stops when central banks and governments pull back on the purse strings—money growth and budgetary deficits. The music stops when we lose faith and confidence. Global policymakers will do everything in their powers to facilitate a soft landing. The music plays on until it stops.

Meanwhile, we are battling an epic war with mother nature; a novel coronavirus that is killing people. In this context, debt can save lives and businesses while public health systems struggle to give us immunity. Shutting down an economy is the price of preventing not overwhelming our health care system. This is good debt. It is cheap debt. Interest rates are low.

Meanwhile, we are battling an epic war with mother nature; a novel coronavirus that is killing people. In this context, debt can save lives and businesses while public health systems struggle to give us immunity. Shutting down an economy is the price of preventing not overwhelming our health care system. This is good debt. It is cheap debt. Interest rates are low.

When central bankers and treasury officials think about our policy path before and after COVID, it is likely they use terms like financial repression and fiscal dominance. Sadly, the two come together.

Financial repression is a monetary policy strategy that deliberately keeps interest rates low—with a preference of interest rates below the inflation rate. Low interest rates encourage people to borrow, which boosts economic growth. It can encourage people to put money into stocks to seek higher returns—good for equity markets. It can deflate away the real value of outstanding debt. Good for debtors, including governments. It can also create nasty imbalances like spikes in housing prices and equity markets that are disconnected from economic fundamentals related to income.

Fiscal dominance happens when fiscal policy dominates monetary policy. With central bank policy interest rates near zero in a low-inflation environment, we rely on fiscal policy, specifically deficit finance, to help stimulate the real economy. A natural political bias toward budgetary deficits becomes a defended fiscal policy when interest rates are low. The nasty problem is that the future is uncertain and interest rates can rise.

Fiscal dominance happens when fiscal policy dominates monetary policy. With central bank policy interest rates near zero in a low-inflation environment, we rely on fiscal policy, specifically deficit finance, to help stimulate the real economy. A natural political bias toward budgetary deficits becomes a defended fiscal policy when interest rates are low. The nasty problem is that the future is uncertain and interest rates can rise.

John Maynard Keynes said that if “If I owe you a pound, I have a problem; if I owe you a million, the problem is yours”. In a world of financial repression and fiscal dominance, the problem is ours. Panic sets in when the music stops.

We have been living in a time of financial repression and fiscal dominance since the 2008 global financial crisis.

There are four stylized facts.

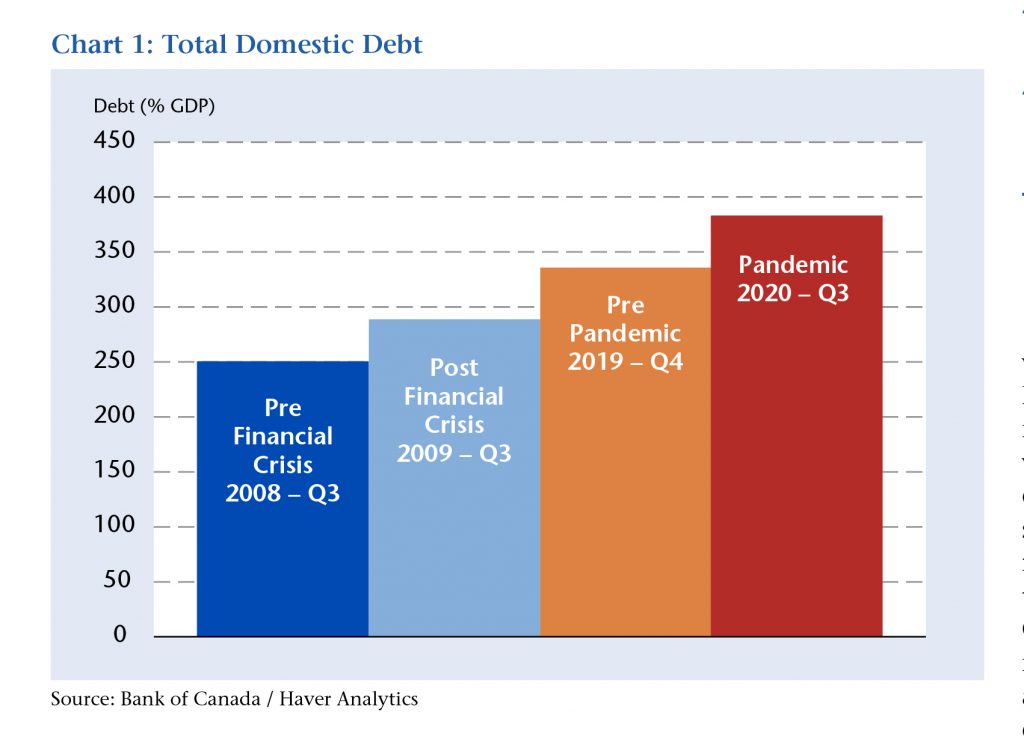

1) Domestic debt in Canada (as elsewhere) is on the rise (Chart 1). It has risen steadily since the 2008 financial crisis. All domestic sectors are contributing—households, financial and non-financial institutions and governments. Every year we break modern records.

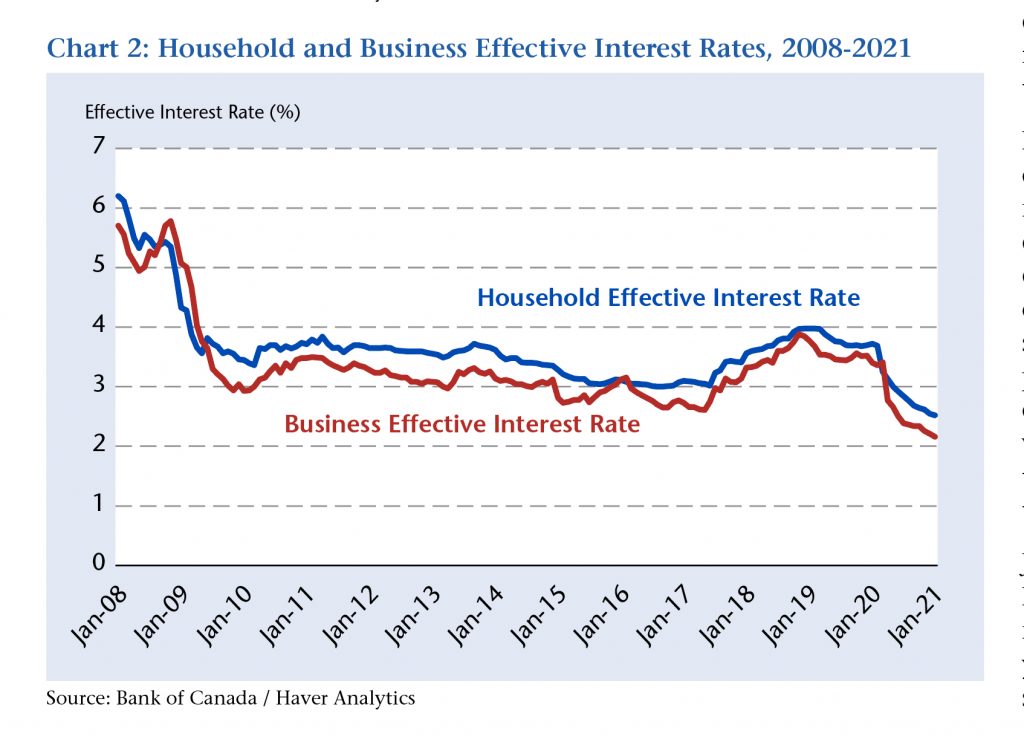

2) Effective household and business interest rates have trended down (Chart 2).

Lower the price of something, we tend to want more. This is true of debt.

3) Carry costs of debt have been reduced. Household debt service ratios (interest costs relative to disposable income) have fallen in 2020 thanks to large federal transfers (deficit financed) and lower interest rates. Federal debt interest costs relative to GDP are at historic lows and have been cut in half since the 2008 financial crisis despite the more than doubling of federal debt in current dollars.

4) Insolvencies were rising modestly before the pandemic and have fallen during the pandemic. In the 2019 election, political parties highlighted the issue of the rising cost of living. This issue has been suspended during the pandemic with enormous monetary and deficit financed fiscal supports.

The policy concerns of ever-increasing debt are twofold.

One, higher debt creates vulnerability risks for economies. This is true for all sectors of the economy. The literature generated by international organizations makes the case that high debt can amplify macroeconomic and asset price shocks. Remember the 2008 financial crisis. Balance sheet recessions can be deep. Stock market and housing prices can fall dramatically. Recoveries tend to be slow and painful.

Two, a long look back at economic history indicates higher domestic debt can increase inflation. While COVID-19 is a deflationary shock, an excessive and ongoing monetary and fiscal policy expansion through the recovery could increase inflationary pressures in the years ahead. Higher price inflation (rising above 3 percent) would force central banks around the world to raise interest rates. A large increase in the cost of debt servicing would destabilize economies. We have a Catch-22 scenario.

The late American economist Hyman Minsky said the seeds of a crisis are sown in complacency. Panics are almost always related to debt. Nassim Taleb, an economist who has studied risk and written books including The Black Swan and Antifragile, has compared risk to efforts to get ketchup out of the bottle. Risk can land hard.

The fall 2020 survey of financial institutions by the Bank of Canada indicates a sharp increase in short and medium-term risks of a shock that could impair the financial system.

Sectors most vulnerable to solvency risk include retail, accommodation and food services, and real estate. Scenarios posing the greatest concern to the financial system include a resurgence of COVID-19. While governments are rushing to vaccinate, the virus is mutating. If COVID-19 stays with us and we have ongoing economic stops and starts, prolonged high unemployment will put great pressure on all sectors of the economy in a high debt environment.

We live in unusual, uncertain and unstable times. Few will argue that debt generated during the pandemic was anything but necessary.

In a post COVID-19 world, policy makers will search for the soft landing. Debt instability risks are real and growing. While some fiscal stimulus will be important to address a weak recovery, new policies to grow the potential sustainable growth rate of the economy are essential. Canada is a rich country. We can build a greener, more inclusive and resilient economy and stabilize our balance sheets. Will we have the political courage to make sacrifices through tax-paid investments and protect fiscal space for the next generation? Can we break the addiction to debt?

Contributing Writer Kevin Page is the Founding President and CEO of the Institute for Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa and was previously Canada’s first Parliamentary Budget Officer. Donya Ashnaei and Elo Mamoh are fourth year economics students at the University of Ottawa.