Canada and China: Rhetoric and Reality

Despite China’s hostage diplomacy in the infamous case of “The Two Michaels” and Beijing’s possible attempted interference in Canada’s last two elections, “we cannot ignore the essential role China must play in addressing overarching global issues like climate change and human health, where there is no room for ‘friend shoring’ of ‘near shoring’”, writes Eddie Goldenberg, long time chief of staff to former Prime Minister Jean Chrétien. For Canada, he thinks “a China strategy– not only for the next sound bite…but for the longer term—requires clear-eyed analysis, thoughtful debate and public understanding. Yet this is hard to find today in the media and in Parliament.”

Eddie Goldenberg

The rise of China in the 21st century not only as an economic superpower but also as a rapidly emerging military superpower is so significant that future historians are likely to look at the period we are now living in as a turning point in world history. How to deal with China going forward will be critically important for Canada’s long-term future in a world of two superpowers.

Canada must not ignore the economic, geopolitical and military challenges posed to global security today by China’s greatly augmented capabilities, and must be open, along with our allies, to a coordinated approach to meet these challenges. At the same time, we cannot ignore the essential role China must play in addressing overarching global issues like climate change and human health, where there is no room for “friend shoring” or “near shoring”.

We must also recognize the economic realities and opportunities created by China’s economic growth. As a middle power, Canada should also be cognizant of the fact that the Global South, many countries in the Indo Pacific, and even in Europe, resist being pushed to choose between China and the United States. They want to maintain good relations with both. Balancing all of this makes the development of a China policy for Canada extremely complicated. However, with difficult geopolitical and economic challenges facing the world, there is a need for calm and reason to prevail with respect to dealing with China. Unfortunately, emotions about China today are running at a fever pitch.

For Canada, a China strategy – not one only for the next sound bite, but for the longer term – requires clear-eyed analysis, thoughtful debate, and public understanding. Yet this is hard to find today in the media and in Parliament. In Canada as in the US, there is far too much Cold War rhetoric, combined with elements of a new McCarthyism.

Of course, constant vigilance is required and we must work with our allies to counter and act on legitimate national security threats from China or other countries. However, given countless examples, including Iraq and Afghanistan, of how often intelligence services have been wrong in the past, there is a real danger if governments take as gospel and develop policy without subjecting to rigorous scrutiny everything told to them by their intelligence services including CSIS in Canada. Media, who rightly fact check what political leaders say, also have an obligation, too often honoured in the breach, to avoid sensationalism and to subject anything leaked by individual employees of intelligence agencies to rigorous scrutiny for accuracy, context and motivation.

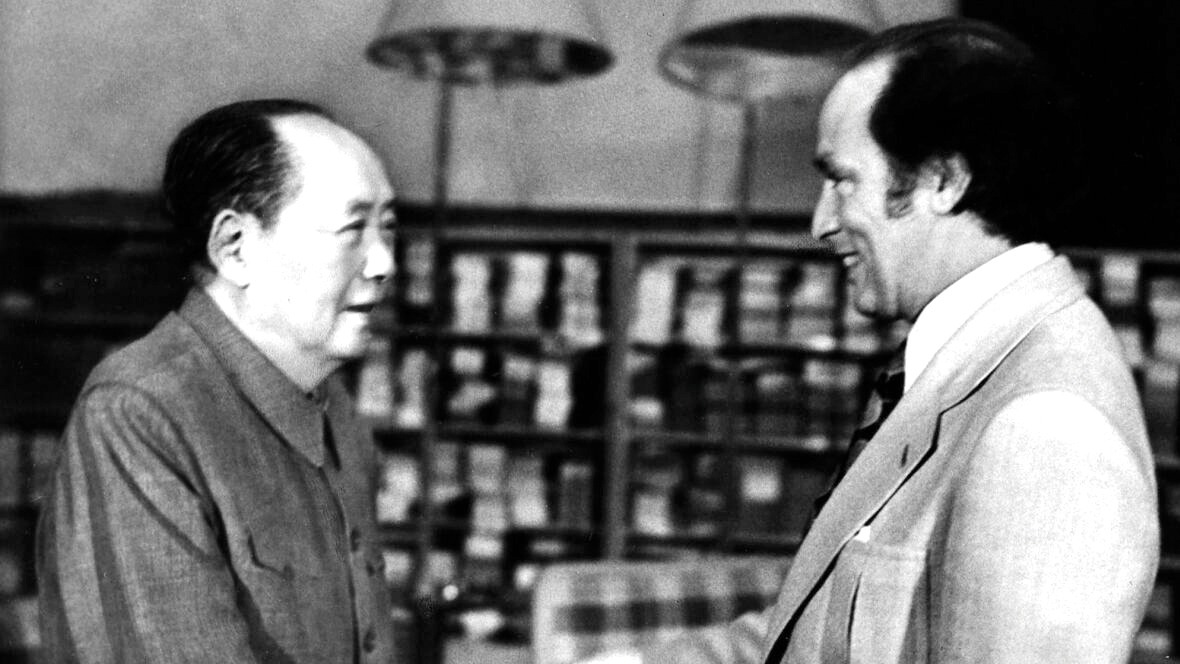

There are important lessons in Richard Nixon’s famous trip in 1972 to meet Mao Zedong. It took place even while the Cultural Revolution, with all its egregious human rights abuses, was in full swing. At the time, compared to today, the Chinese economy was almost nonexistent; there was no significant trade between China and the US or between China and the West in general. Nixon did not travel for economic reasons or in order to bring democracy to China. Like Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau, whose diplomatic recognition of China in 1970 led the western world in recognizing that China must be encouraged to take its place at the global governance table rather than remain excluded, Nixon believed that for geopolitical reasons it was important that China not be isolated or left in the arms of the Soviet Union. Nixon and Henry Kissinger were of the view that it was necessary to engage with China regardless of the nature of the regime in Beijing.

If the geopolitical context at the time of Richard Nixon required engagement with China, surely today’s global economic interdependence as well as existential threats to humanity from climate change and pandemics, and Russia’s aggression in Ukraine makes engagement and dialogue with the China of Xi Jinping not a policy choice but a policy imperative.

Difficult as it may seem in the current climate, it would be short sighted and wrong at this time of rapid and profound global transition to throw away a political, cultural and economic history with China that dates back to the 19th century. Canadians must focus on the long game even beyond the current Xi Jinping regime. To do that requires an understanding that throughout Chinese history, fundamental government policies have often changed in significant ways as one dynasty followed another, and in recent times as one leader followed another.

As well, in China today, under the radar and away from public scrutiny policy develops, evolves and sometimes changes quickly in unpredictable ways, as in the case of the recent surprise sudden lifting of COVID-19 restrictions. Just as it would have been wrong to abandon our long-term policy towards the US because of Donald Trump, it would be wrong to develop long-term policy towards China solely in relation to where Xi Jinping stands today. Nor should we rule out the possibility that his successor, whether in five or 10 years from now may once again pursue progressive reform as the harmful effects of some of Xi’s policies become more evident. Shutting Canada out of an economic and people-to-people relationship with China today would be a serious handicap in pursuing longer-term geopolitical understanding as well as economic opportunities for tomorrow.

It is in Canada’s self-interest that relations with China be viewed and developed not only through the lens of Canadian values but also through an economic perspective. Canada cannot only trade or engage diplomatically with countries with whom we share common values. No other country acts that way. While some Western countries today are ramping up their political rhetoric with regard to China, the business communities of these same countries continue to grow their economic, investment and trade relationships with China in a significant way. There is over $2 billion a day in trade just between the US and China. Direct American private sector investment in China has risen during both the Trump and Biden administrations despite US government policies with respect to China. Today that investment is in the order of $120 billion.

Despite all the rhetoric in Canada about China, Canada’s exports to China in 2022 were at a record high level. While there may be some decoupling of certain critically important supply chains, a general decoupling from China is not feasible. China is simply too big to ignore and impossible to isolate.

Despite all the rhetoric in Canada about China, Canada’s exports to China in 2022 were at a record high level. While there may be some decoupling of certain critically important supply chains, a general decoupling from China is not feasible. China is simply too big to ignore and impossible to isolate.

Sophistication and careful reflection, not empty rhetoric, are required for Canadian values to be incorporated as one element of our policy towards China in a way that actually contributes towards attaining our objectives. Advocating being “tough on China” may make us feel good and virtuous, but if the objective is not simply to feel virtuous but rather to have a positive influence on China, the evidence so far is that resolutions in parliaments, trade or other sanctions, or denunciations by western governments alone simply do not work and are often counter-productive. One of the prime reasons they are counter-productive is because of a lack of understanding of Chinese history, of a very proud civilization and a culture that is more than 3,500 years old.

For many centuries China was the richest and most advanced country in the world, the “Middle Kingdom,” with impressive achievements in the arts, literature, education, public administration, in science and technology. Fierce pride in being Chinese long predates XI Jinping and the Communist Party and will remain long after he and even the party have passed from the scene. However, from the middle of the 19th century until 1949, a period of time that is a mere blink of the eye in terms of Chinese history, China was subject to foreign invasion, dismemberment, civil war and extreme poverty.

It would be a fundamental error for Canada to develop a China policy and a China strategy without taking into account not only the visceral pride the people of China have in being Chinese, but also, in part as a result of the “century of humiliation,” their long standing and sometimes justified suspicion of the motivation of outsiders.

Obviously, and with reason, human rights issues and geopolitics colour the discussion today about how the government of Canada and even Canadian business should deal with China. Nevertheless, the protectionism of the Biden and Trump administrations has reminded us that Canada is economically vulnerable and cannot continue to hope to thrive exclusively in the US slipstream. With the Inflation Reduction Act and other American legislative and administrative actions, economic protectionism is rampant in the US. “Friend shoring” or “near shoring” unfortunately are words much more synonymous with American protectionism than they are with Canadian economic opportunity. We need to develop an independent analysis of global developments and China’s role in a changing global order. This means collaborating broadly across nations in line with our own multi-lateral traditions – not just echoing US views which are driven by their own specific geopolitical goals. Canada needs to learn to better protect its own interests which are not always in sync with those of the US.

Canada is far from alone in having a trading relationship with China. China is the largest trading partner of most countries in the world. The hundreds of millions of people taken out of poverty and the development and growth of a large middle class in China have created enormous economic opportunities for China and the world. Those who suggest that the Canada-China trading relationship is simply for the profit of “Big Business” are wrong. China is the world’s largest buyer of most of our major export commodities. Canada is only one of many possible suppliers of lobster, canola, beef, pork, mineral resources, lumber, and even pet food. These industries are at the heart of the Canadian economy and benefit workers in these industries – many of whom live in rural Canada. China is also an important destination for Canadian investment. China is not only a historic market more than a century old for the Canadian financial services industry, it is increasingly important to the thousands of Canadians who work in that industry.

The recently announced Indo Pacific policy cannot be a substitute for our economic relationship with China. Those who think it is, are dreaming in technicolour. China is the predominant economic power in Asia and the largest trading partner of the countries in the Indo Pacific. Over the last two years, despite growing political tensions, 15 Pacific nations, including Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand entered into the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership with China, which binds them closer together economically. Canada needs to expand trade both with China and with the countries of the Indo Pacific. While increased trade with the Indo Pacific is clearly good for Canada, it can complement but will not replace what we sell to China today. Because China is so central to the economy of all Asian countries, divorcing ourselves from China would effectively undermine many Canadian economic relationships in the Indo Pacific.

Winston Churchill, who was not known as an appeaser, famously said that it is better to “jaw-jaw than to war-war.” When Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin of Israel was criticized for meeting and negotiating with the leadership of the Palestine Liberation Organization, he responded that you do not need to make peace with your friends; you need to make peace with your enemies. China is not an enemy, but in some areas, it is very much a strategic competitor. This makes engagement even more important. Today bilateral meetings between China and many other countries are regularly taking place at the level of heads of government, ministers and senior officials on a whole host of issues, including trade and investment, climate change, security, and other geopolitical issues

But there are almost no bilateral discussions at a high level between Canadian and Chinese officials. Unless Canada wishes to engage in a solitary counter-productive freezing of dialogue with China, the Canadian government would do well to be inspired by Churchill’s words. Canada should renew high-level bilateral discussions with China both in areas where we have legitimate fundamental disagreements, but particularly in areas like sustainable development, health care, agriculture, financial services, tourism, and educational exchanges where the two countries should be able to agree to cooperate, and where decoupling is in no one’s interest.

How we engage both in economic matters and particularly where there are fundamental differences will depend on whether the objective is to create good headlines at home to respond to opposition or media rhetoric or whether it is to seek constructive solutions to problems as well as to pursue opportunities. Engagement does not mean appeasement; it means respectful dialogue and cooling of unproductive rhetoric. Successful engagement makes it possible to disagree without being disagreeable, to listen to each other respectfully without lecturing.

It is in the interest of Canada to pursue an engagement strategy with China that takes into account our values and also corresponds to our economic, environmental and security goals. These require a clear-eyed assessment of benefits and risks. Withdrawing from the table is not a viable option.

Eddie Goldenberg was Chief of Staff to former Prime Minister Jean Chrétien and is currently a partner at Bennett Jones, LLP in Ottawa.