Can We Plant Trees and Maintain Forest Biodiversity?

In Canada, planting is an important tool for ensuring that forests sustain myriad different values, writes Alice Palmer/Adobe

In Canada, planting is an important tool for ensuring that forests sustain myriad different values, writes Alice Palmer/Adobe

September 16, 2024

Forests are integral to biodiversity, global carbon balance, and human well-being. This makes deforestation (the conversion of forested land to other uses) and forest degradation (the reduction of a forest’s ability to provide the same environmental and/or economic value that it once did) major global environmental issues. When forestland is cleared permanently for agriculture, grazing, or urbanization, its carbon is released into the atmosphere and the land’s carbon-sequestration potential ceases. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (UNFAO) estimates that 11 percent of global carbon emissions are caused by deforestation and forest degradation.

The European Union’s new Regulation on Deforestation-free Products (EUDR) strives to end global deforestation. As its name would suggest, the EUDR is designed to ensure products entering the EU, including forest products, soy, palm oil, cocoa, coffee, beef and rubber, and their derivatives, have not contributed to deforestation or forest degradation. As of December 30, 2024, all shipments of these products in the EU must be accompanied by a due diligence statement and detailed geolocation references, showing where the products originated. Palm oil and rubber producers in Southeast Asia, beef and soybean growers in Latin America and Australia, and coffee and cocoa farmers in Africa will all be affected.

Canadian farmers and forest products companies will be affected too. The good news is that Canada is almost deforestation-free: annually, less than 0.02 percent of Canadian forests are converted to other uses. Further, our forestry regulations are among the most stringent in the world. Less than 0.5 percent of our forests are logged each year, and logged areas are promptly reforested. However, this does not mean we are off the hook.

Two Planting Perspectives

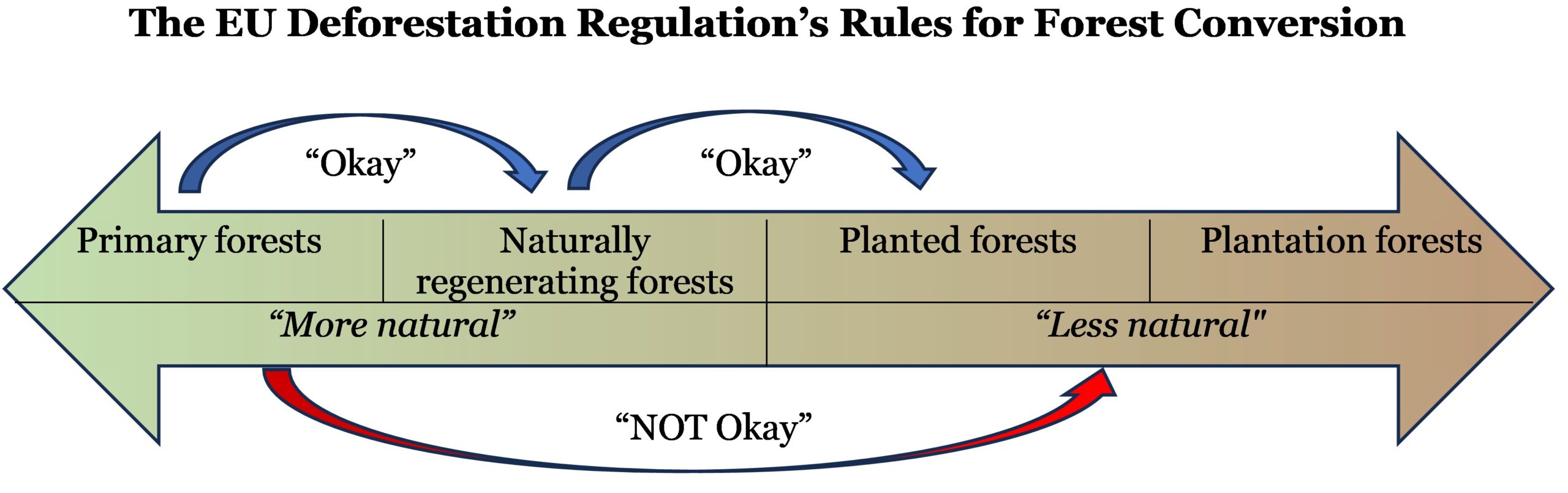

Ironically, Canada’s tradition of prompt reforestation runs contrary to the EUDR rules – at least at first glance. Article seven of the EUDR defines forest degradationas: “The conversion of primary forests or naturally regenerating forests into plantation forests or into other wooded land, or primary forests into planted forests.”

In other words, forest management that reduces a forest’s degree of naturalness beyond a prescribed limit is considered to be degradation. According to the EUDR, it’s okay to convert a primary forest (i.e., a forest that has no “clearly visible indications of human activities”) into a naturally regenerated forest, but not okay to convert it into a planted forest. Further, it’s okay to turn a naturally regenerating forest into a planted forest, but forbidden to turn it into an intensively-managed forest plantation. Figure 1 represents a visualization of the concept.

From a European perspective, this makes sense. Europe is much more densely populated than Canada, and many European forests were in fact re-established in the late 19th and 20th centuries after being heavily over-exploited by previous generations. Not all of the trees planted were native to Europe. Indeed, Sitka spruce – native to the west coast of North America – was planted throughout much of Northern Europe. In Europe, “planted forests” can indeed be quite different from “naturally regenerating forests.”

From a Canadian perspective, however, the EUDR definitions seem both arbitrary and confusing. Why? Because there is really no difference between a “naturally regenerated forest” and a “planted forest” in Canada. In contrast with the forest practices of some parts of Europe (and many other parts of the world), we don’t plant non-native species here. After logging, we reforest with the same tree species that were there before.

Fortunately for Canada, the EUDR’s definition of “naturally regenerated forests” does allow some leeway for planting. The EUDR includes “forests for which it is not possible to determine whether planted or naturally regenerated” in its definition of “naturally regenerated forests.” Most (if not all) Canadian second- growth forests would meet this criterion.

Will these arguments be enough to convince European policy makers that Canadian forestry practices do not represent a conversion from “natural” to “unnatural?” One can only hope.

Why Do We Replant?

If the EUDR policies threaten to brand tree planting as “degradation,” why not just let our forests regenerate naturally? Although planting is common in Canada, it isn’t 100% necessary. In nature, if a forest burns down, blows down, or gets eaten by insects, it usually grows back on its own. In the newly established sunlight, pre-existing seeds will sprout, and new seeds will blow in from adjacent forests. With less overhead competition, surviving understory trees (the vegetation that grows between the forest canopy and the forest floor) “release” and grow more quickly.

However, the process of natural regeneration can take a long time. Often, the first species to establish themselves after a disturbance are what is known as “pioneer” or “early seral” species: sun-loving species including grasses, shrubs, and rapid-growing (yet less commercially valuable) trees such as alder and aspen. These pioneer species can initially out-compete the slower-growing “climax” species that existed in the forest before the disturbance. Also, if dense brush prevents trees from getting established, there can be gaps in the tree cover.

The benefit of planting versus waiting for natural regeneration is that planting speeds up forest reestablishment and ensures that harder-to-reestablish species are included in the mix. While this is obviously advantageous from a commercial perspective, planting also ensures that other forest benefits such as carbon sequestration and soil stabilization occur more quickly.

The Science of Reforestation

In Canada, we typically aim to regrow the tree species that were on the ground before an area was logged. Prior to logging, the site is surveyed, and a detailed reforestation plan is created, based on the site conditions and the existing tree species.

Foresters also recognize that naturally-regenerated trees often join those that were planted. Some species regenerate so abundantly that foresters often leave them out of their planting prescriptions, even though they anticipate the species will dominate the mature forest. For example, in forest openings on the west coast, it doesn’t take long before a thick, green carpet of western hemlock seedlings covers the forest floor. So, even if only a single species is planted, the second-growth forest will often contain more.

When foresters opt to re-plant a forest, the seedlings come from local nurseries, using seed cones harvested from local forests. This is important, as trees are genetically adapted to their own latitude.

Reforestation and Climate

As the world warms, Canada’s forests are becoming increasingly prone to drought, insects, and wildfire. This presents both a challenge and an opportunity for our reforestation programs.

If an area becomes warmer and drier, an individual tree can’t pack up and move north. However, whole forests can adapt over time: trees that are genetically better adapted to the new conditions thrive, and ones that are less adapted die out. Unfortunately, this process is very slow. If the climate warms rapidly, our forests may struggle to adapt fast enough, and forest health may suffer.

Selecting seed cones from sites slightly further south than where the seedings will be planted can help forests adapt to climate change. Research into this practice is ongoing.

Another issue affecting Canadian reforestation practices is wildfire mitigation. In recent years, we have seen an increase in extreme wildfire behaviour in Canada. With climate change occurring, this pattern is likely to continue – necessitating a change in forestry practices.

Since we primarily log conifer species in most of Canada, these are the species we typically aim to have in our second-growth forests. However, hardwood species such as aspen are less flammable than softwoods. When out-of-control wildfires are racing across the landscape, they tend to slow down when they hit hardwood stands. Therefore, adding “firebreaks” of hardwoods onto the landscape is becoming an increasingly important wildfire mitigation strategy.

Natural, Sustainable and Strategic

Does replanting a forest really cause degradation, or in other words, reduce a forest’s ability to sustain ecological and economic benefits? In Europe, in the past, perhaps it did. Foresters in the 1800s and 1900s may not have considered the wide range of ecological values that we do today.

Today in Canada, however, planting is an important tool for ensuring that forests do sustain a myriad of different values. Not only does planting ensure sustainable timber production in the future, it also contributes to biodiversity, carbon sequestration, and soil stability – among other things. Furthermore, it can be a useful strategic tool for helping forests adapt to climate change.

Canadians love our forests. Therefore, sustainable forest management, including tree planting, is important to us too.

Alice Palmer is a forest industry consultant based in Richmond, BC. Follow her blog, Sustainable Forests, Resilient Industry, on Substack.