Can Ukraine Survive Trump’s Assault on the World Order?

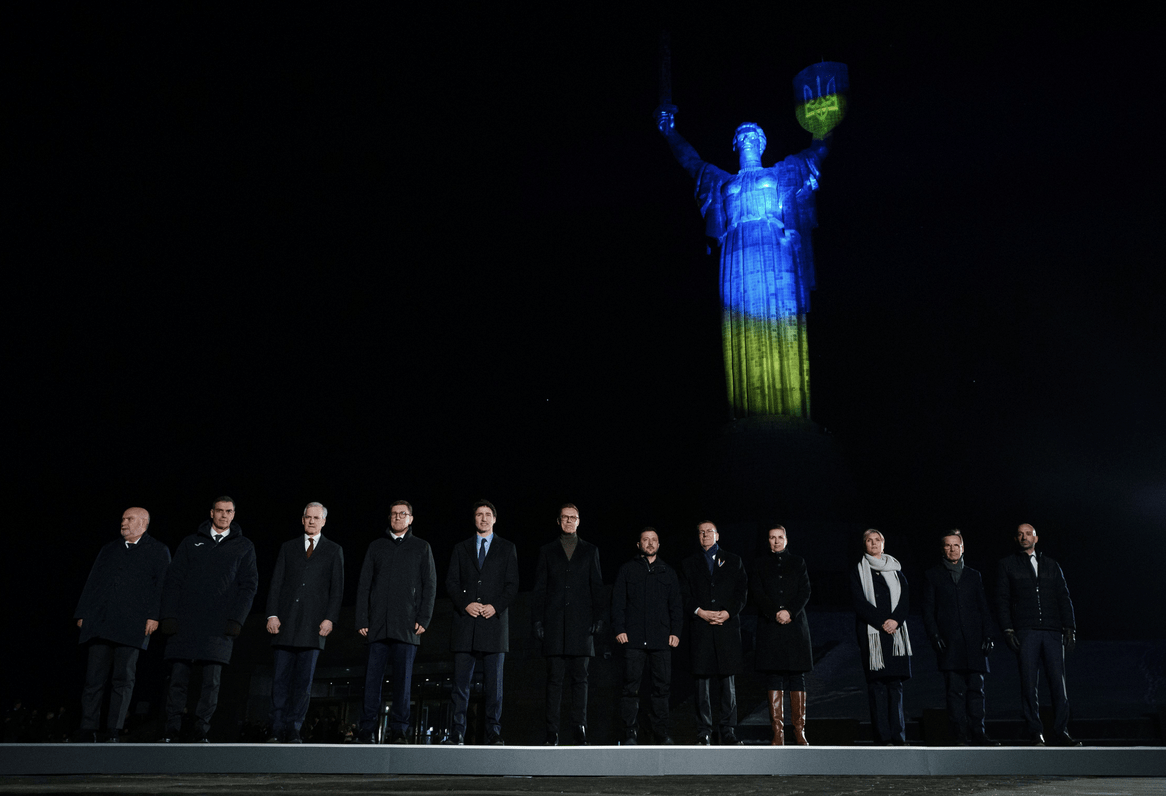

Volodymyr Zelensky (centre) with Western leaders in Kyiv on the third anniversary of Russia’s invasion, February 24, 2025/Adam Scotti photo

Volodymyr Zelensky (centre) with Western leaders in Kyiv on the third anniversary of Russia’s invasion, February 24, 2025/Adam Scotti photo

March 1, 2025

“Something has to change.” This sentiment had become a familiar refrain among Ukrainians toward the end of 2024, approaching three years of gruelling war for their country’s survival. The war has yielded untold casualties on both sides, 20 per cent of Ukraine’s land mass under occupation, and psychological trauma for millions living under constant air-raid sirens and shelter-in-place orders. Little doubt, then, that many Ukrainians were cautiously optimistic that a new Trump administration in the United States might lead to something different.

Western allies had been giving them just enough support to not be annihilated, but not quite enough to win.

Maybe, just maybe, this new deal-maker American president – who put his reputation on the line with promises of a quick end to the war – might shake things up enough to allow Ukraine to win. More arms? Fewer restrictions on the arms being provided? A less bureaucratic approach to the use of frozen Russian assets as a war chest? A braver stare-down of the Kremlin’s repeated “red lines”?

Well, something has indeed changed. The ground has shifted rapidly – not only under Ukraine, but across the European continent and indeed the entire global geopolitical environment. And not in the interests of either Ukraine or global security.

In bewilderingly quick succession, Donald Trump pulled Russia out of its international pariah status while extracting no concessions in return. He called Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky a “dictator without elections” – falsely accusing him of refusing to hold elections and repeating the Kremlin narrative about Zelensky’s alleged illegitimacy – while phoning Vladimir Putin, who remains under International Criminal Court arrest warrant for war crimes and mass abduction of children. Trump validated the true dictator – who fixes elections, imprisons journalists, defenestrates critics and serves polonium or Novichok tea to his political opponents – while denigrating the hero. That should have been a warning to Ukrainians.

Trump dispatched envoys to state publicly that recovering all occupied Ukrainian land was a non-starter, as was NATO protection. He signalled to European NATO partners that any conflict on the continent is Europe’s problem – not America’s and not NATO’s. He directed his United Nations ambassador to vote against the renewed UN General Assembly resolution on Ukraine which called for a “just and lasting peace”, reaffirmed Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity within its internationally recognized borders, demanded the withdrawal of Russian military forces from Ukrainian territory, and demanded accountability for war crimes.

True – the resolution still passed overwhelmingly, but the United States’ reversal was a major moral victory for Russia. Not even China and Iran voted against the resolution, but America found itself in bed with a small handful of autocratic countries, including Russia itself, North Korea, Russian-puppet Belarus, and proto-fascist Hungary.

Additional U.S. moves have served to further parrot Kremlin propaganda: America’s refusal to sign a World Trade Organization statement because it acknowledged that Russia invaded Ukraine; Administration officials’ refusal to acknowledge in congressional hearings that Russia is the aggressor; public musings that Russia’s invasion was justified by NATO expansion….

And then, most shockingly, Trump and his vice president J. D. Vance ganged up on Zelensky in the Oval Office Friday in what was supposed to be a routine bilateral photo-op, which instead degenerated into an attempt to publicly humiliate Zelensky, while simultaneously shaking him down for his country’s critical minerals. While Zelensky instantly became a global hero to many for not bending the knee, kissing the ring and swallowing earfuls of Russian propaganda, his dignified pushback did, unquestionably, harm Ukraine’s relations with the U.S.

Munich 2025 was like a ‘break’ in billiards – the opening strike that sends all the balls rolling in different directions. It’s uncertain how the table will look when the balls stop rolling, but we know it will be different.

This is a seismic shift in geopolitical balance. While it seems unthinkable to credit a figure like Donald Trump with such disproportionate impact, it may even be the beginning of the end of the international rules-based order that has endured since 1945. Indeed, it increasingly appears to be a re-emergence of the might-is-right imperial states model that dominated the 18th and 19th centuries, ravaged Europe in the two world wars of the 20th, and which was thought to have been consigned to history with the formation of the post-WWII multilateral institutions.

The mid-February Munich Security Conference may prove to have been a turning point for that international order. It was during Munich (though in absentia) that Trump first announced he would negotiate with Putin and that Ukraine would not be invited to the talks, while his vice president gave European democracies a dressing-down. Munich immediately drew ominous references to its namesake conference of 1938, when European powers – notably Great Britain – met in the same Bavarian city to offer an appeasement deal to Adolf Hitler: Austria and part of Czechoslovakia in exchange for peace.

Munich 2025 was like a “break” in billiards – the opening strike that sends all the balls rolling in different directions. It’s uncertain how the table will look when the balls stop rolling, but we know it will be different.

And the balls are rolling. Zelensky left Washington without a signed “economic security” agreement with the States, and with his personal relationship with Trump strained. France and Britain are scrambling to assess feasibility of European troops in Ukraine as peacekeepers or peace enforcers. Smaller NATO countries – particularly the Baltics – are quietly acknowledging to themselves that Article 5 protection of NATO is de facto no longer valid, and depends on the whim of the White House on any given morning. The extremist German AfD party is being championed by the Oval Office’s chief lieutenants – Elon Musk and J.D. Vance. Global democratic accountability projects have been slashed overnight by the virtual killing of USAID.

Trump is displaying a sycophantic fixation with Putin, and has already offered to globally reintegrate Russia, both diplomatically and economically. And, perhaps most importantly, the White House is waging or threatening economic war against its traditional allies – Canada, the European Union, Japan and others – in an apparent bid to dissolve the common front of liberal-democratic nations united against the world’s emerging autocracies.

As for Ukraine, they will fight on. They have to. To recall a well-used refrain of the current war, “If Russia stops fighting, there will be no war. If Ukraine stops fighting, there will be no Ukraine.”

While one tends to think of this war as having started in February 2022, it really started in February 2014 when Russian troops moved into Ukraine’s southernmost peninsula, Crimea. And in full context, the last decade has been but the latest manifestation of an 800-year history of repeated attempts by Russia (and its predecessor Muscovy) to seize all Ukrainian lands and erase the nation’s language, culture and identity.

But it is precisely this history – this lived experience – that instilled in the Ukrainian people the resolve to stand up against the daunting odds and push back against a nuclear-armed power more than three times their size. History had taught Ukraine what the stakes actually are: this is not a land skirmish over some disputed border region. This is a fight for Ukrainians’ very survival.

This resolve to survive fuelled Ukraine’s resistance against the Bolsheviks after the First World War. It inspired Ukraine’s resistance against both the Soviets and the Nazis during World War Two. It sparked an immediate declaration of independence when the Soviet Union was sufficiently weakened by the principled Republican administration of Ronald Regan. And it now drives the resistance – three years on – in a war most analysts had predicted would be over in three weeks and some predicted would be over in three days. And the Ukrainians will continue their fight through a combination of grit, innovation and existential resolve. With or without American help.

The world order is under assault, with Ukraine at its epicentre. But when the dust settles, it may well be the Ukrainians who will re-educate Americans on what democracy means, why it is important, and that there are higher principles worth fighting for.

Contributing writer Yaroslav Baran is co-Founder of Pendulum, a political analysis and communications consultancy. He is also chair of the board of the Parliamentary Centre – an Ottawa-based NGO.