Can India Challenge China as Asia’s Great Power? Ask its Neighbours.

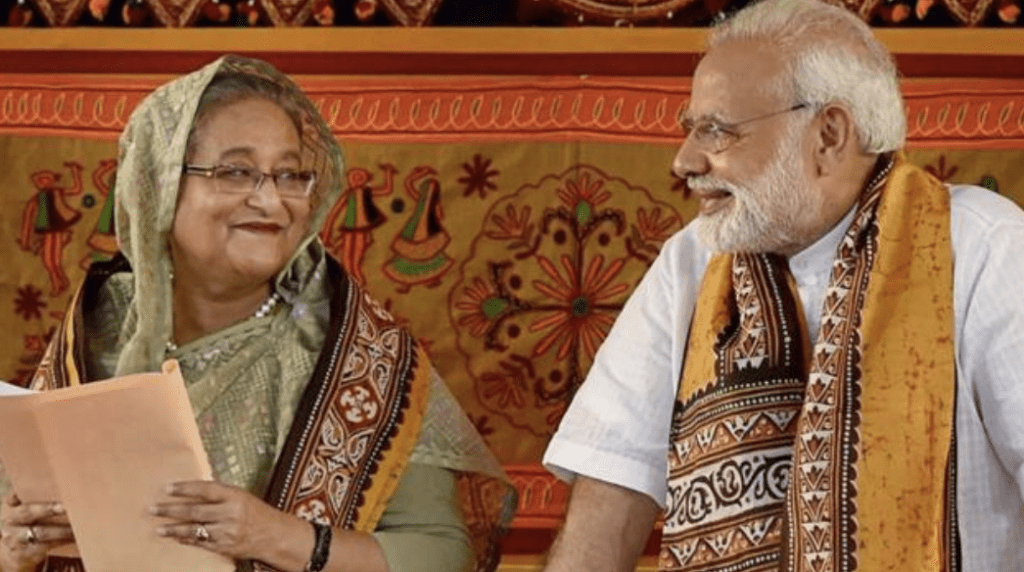

Ousted Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina with India’s Narendra Modi/PTI file

Ousted Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina with India’s Narendra Modi/PTI file

By Aftab Ahmed

September 3, 2024

The Washington Post recently revealed that, for a year before Bangladesh’s election last January, which was boycotted by the opposition and widely disparaged, the government of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi had pressured the Biden administration to back off its demands for a free and fair election.

It was a move aimed at protecting New Delhi’s ally, the autocratic Sheikh Hasina, who “won” the discredited vote but by August had been deposed by a student-led mass uprising. The United States had been vocal about human rights abuses in Bangladesh since Biden took office, imposing sanctions on a Bangladeshi police “death squad” accused of extrajudicial murders and abductions at Hasina’s direction. But this stance softened after India’s intervention.

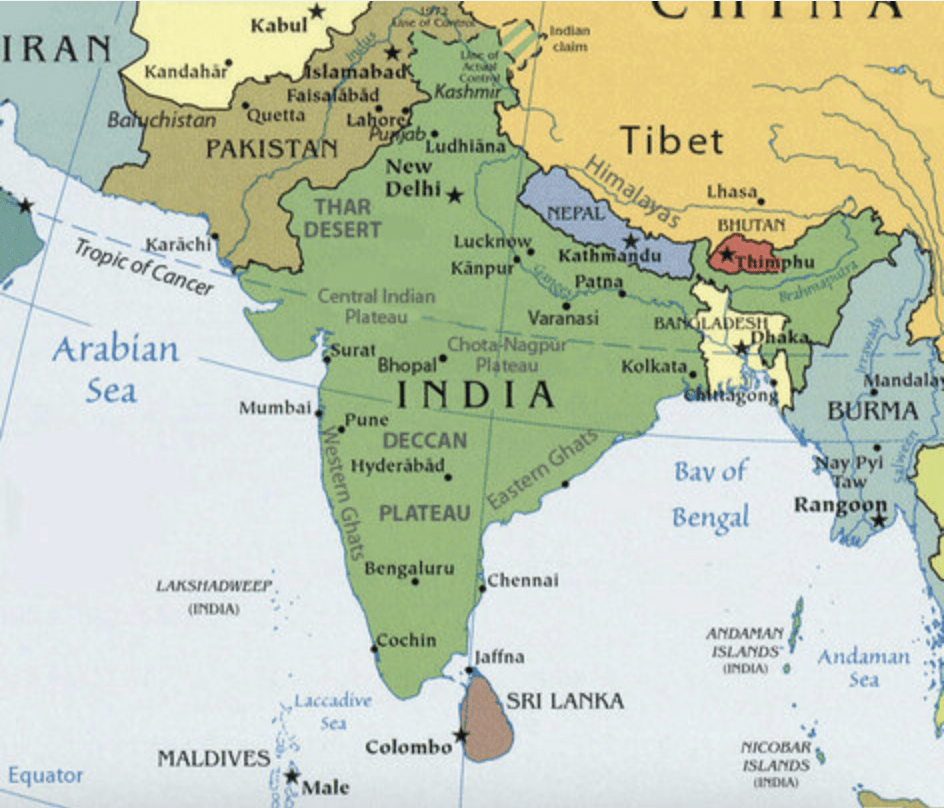

weebly.com

Among India’s immediate neighbours in what was once widely referred to in geopolitical terms as the “Indian subcontinent”, now more neutrally labelled “South Asia”, are Bangladesh, Bhutan, the British Indian Ocean Territory (United Kingdom), India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. In geographical terms, Afghanistan is often included in the term “South Asia” but is not for the purposes of Indian foreign policy in the region. Within this geopolitical group, geography and history grant Bangladesh — divided into Pakistan as majority-Muslim East Bengal during the Partition of British India, then born as Bangladesh from its 1971 war of independence — disproportionate value in India’s immediate sphere of influence.

The translation of that geopolitical value into Modi’s security and political protection of Hasina’s regime was a major focus of the anger fuelling the student protests that ousted her. Bangladesh’s interim government, led by Nobel peace laureate and microcredit pioneer Muhammad Yunus — for years Hasina’s most public target of relentless political persecution — has revoked her diplomatic visa and may demand her extradition from India, to where she escaped on August 5 by military helicopter.

Which is why the final misjudgment about Hasina made by New Delhi and passed on to Washington was important. It disrupted Washington’s democracy promotion efforts in the Indo-Pacific and exposed two uncomfortable truths about India, a country the West needs to continue courting for strategic reasons, including but not limited to its $4 trillion economy, its status, as of 2022, as the world’s most populous country, and its significant international diasporic footprint.

Narendra Modi with Xi Jinping, Wuhan, China in 2018/India PBI handout

Narendra Modi with Xi Jinping, Wuhan, China in 2018/India PBI handout

First, while the West justifiably views the world’s largest democracy as a bulwark against an authoritarian China, New Delhi’s foreign policy, as an extension of its ruling party’s hyper-nationalist, right-wing agenda, involves the blanket shielding of its preferred political allies, regardless of how disconnected they are from their own people and whatever the cost of that support may be. That approach to influence-trading echoes Beijing’s economic support for anti-democratic leaders across continents, notably through its Belt and Road initiative.

Second, India imposes its security interests unilaterally by leveraging intimidation rather than engaging in diplomacy over unresolved public policy issues that could bring about mutual, rather than one-sided, benefits. Again, a preference for belligerence that aligns, perhaps to a lesser and more subtle extent, with its BRICs partners China and Russia’s marginalization of diplomacy as a means of dispute settlement.

These changes in New Delhi’s foreign policy under an increasingly autocratic Modi represent a clear departure from the diplomatic posture of his predecessors, who, despite variations in rhetoric, maintained a relatively consistent approach during the three decades between Indira Gandhi’s assassination in 1984 and Modi’s rise from controversial chief minister of Gujarat to prime minister in 2014.

Indeed, the Gujral Doctrine articulated by Prime Minister Inder Kumar Gujral in the 1990s defined India’s role as a big brother in the region, based on the belief that the country’s strength and stature were intrinsically linked to the quality of its relations with its neighbours — that India had to be at ‘total peace’ with those countries in order to contain Pakistan and China’s power in the region. A focus on non-reciprocal goodwill, non-interference, respect for sovereignty, and peaceful dispute resolution to build trust was embedded in the regional policy architecture. Today, India favors bilateralism and heavy-handed assertiveness over multilateralism and regional cooperation.

One Reddit wag’s altered version of the Hasina-Modi bilateral relationship

One Reddit wag’s altered version of the Hasina-Modi bilateral relationship

In the Modi era, India has grown oblivious to the realities of its neighbours: this is the principal driver of the anti-Indian sentiment currently sweeping the region — a warning that New Delhi may pay a price if it fails to recalibrate its diplomatic toolkit toward regional wellbeing.

At the same time, at the political level, a de facto shift toward closer ties with China is unfolding in the region. There are three perception-driven factors behind this. First, public sentiment perceives Beijing as less intrusive in domestic political affairs than New Delhi. Second, India has failed to promote robust people-to-people relations that could establish it as the organically embraced, legitimate moral leader of the region, capable of voicing the collective interests of the neighbourhood on the global stage. Having less historical baggage, with fewer past grievances and a cleaner slate with India’s neighbours, Beijing has leveraged India’s missteps in these areas to strengthen its position in the region.

Third, Modi’s Neighbourhood First policy, which in reality relies on behind-the-scenes head-of-government interpersonal ties, has fueled anti-Indian sentiment among citizens of neighbouring countries. The outcome is bad for New Delhi: India is seen as an antagonistic, aspiring hegemon.

Western media outlets, when zeroing in on regional geopolitical patterns, often spotlight India’s perpetually fraught relations with Pakistan – now seemingly at a dead end – the Taliban’s takeover in Afghanistan, and Myanmar’s ongoing civil war. Other countries often fly under the radar.

Consider Nepal, a country that has conventionally operated under New Delhi’s political direction. A blockade imposed by India in response to Nepal’s new constitution in 2015 resulted in acute shortages of fuel, medicine, and other essential goods during a critical post-earthquake recovery period. And Indian support for the related 2015 Madhesi protests, which demanded greater representation for those perceived to be pro-Indian in the Nepalese political system, was viewed as foreign interference. The decision to build a road through the Lipu Lekh region, a disputed territory claimed by Nepal, without consulting Kathmandu, further inflamed tensions. And, New Delhi has faced criticism for its handling of cross-border water management, with Kathmandu accusing it of mismanaging dam operations on rivers that flow into Nepal, causing flooding and destruction of farmland and property.

In Sri Lanka, during the 2018 constitutional crisis, India’s lack of a clear stance and delayed response were perceived as signs of diplomatic indecisiveness. Although India provided a $1 billion credit line and other financial assistance packages during Sri Lanka’s economic crisis in 2022, these efforts were overshadowed by China’s strategic long-term investments, such as the 99-year lease of the Hambantota port and funding for the Colombo Port City project.

The Maldives-inspired ‘India Out’ campaign has gained traction across South Asia/The Maldives Journal

The Maldives-inspired ‘India Out’ campaign has gained traction across South Asia/The Maldives Journal

In the Maldives, India’s influence has been waning. The election of President Mohamed Muizzu, who ran on a strong anti-Indian platform, marked an unprecedented shift in Maldivian foreign policy. Muizzu’s India Out campaign, calling for the withdrawal of Indian military personnel, echoed nationwide discontent with Indian military presence in the islands and gained traction across the region, including and most forcefully in Bangladesh.

In Bhutan, long considered a protectorate of New Delhi, India’s influence is being challenged as the landlocked kingdom seeks to diversify its international ties. The 2017 Doklam standoff between India and China (not to be confused with the 2020 border skirmish between the two at Ladakh, 1,300 kilometres to the northwest), which occurred on territory claimed by both Bhutan and China, put Thimphu in an awkward position as New Delhi acted on its behalf without thorough consultation. Bhutan’s decision to sign a Memorandum of Understanding with China in 2021 to expedite boundary negotiations despite India’s objections signaled a move toward a more autonomous foreign policy. India also controls Bhutan’s most important source of revenue, its hydroelectric power, a dependence that many Bhutanese believe restricts their long-term economic aspirations.

Lastly, and most recently in the international spotlight, there is Bangladesh. Since 2009, Hasina, with India’s support, had presided over a state apparatus notorious for overseeing extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, public sector corruption, a compromised banking system, and for facilitating money laundering, among other abuses.

Protesters attempt to demolish the statue of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Bangladesh’s liberation war icon and Sheikh Hasina’s father, in Dhaka on August 5/AP

Protesters attempt to demolish the statue of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Bangladesh’s liberation war icon and Sheikh Hasina’s father, in Dhaka on August 5/AP

According to the United Nations, over 650 deaths, largely aimed at crushing civic dissent, have been confirmed between July and August 2024, with Dhaka’s interim government putting the number at over 1,000. What began as protests over a public sector recruitment policy quickly escalated into a non-negotiable demand for Hasina’s resignation.

India has repeatedly failed to address key concerns from Bangladeshis: a fair water-sharing agreement, better management of dam releases during the monsoon season to prevent flooding, an end to arbitrary border killings by Indian forces, and visa liberalization for Bangladeshis. Regardless of the close personal ties between Modi and Hasina, these issues were consistently ignored, reinforcing the perception that their bilateral quid pro quo was based on the deprivation of Bangladeshis, not their benefit.

The dissatisfaction of Bangladeshis is just part of a regional backlash against India’s support of corrupt leaders at the expense of their citizens. Now, as anti-Indian sentiment expands, New Delhi faces the challenge of rebuilding trust, contending with the consequences of a policy that has prioritized political expediency over authentic engagement with its neighbours, reflecting its Hindu nationalist vision of an Akhand Bharat: an undivided South Asia where its neighbours function as satellite states at the behest of New Delhi rather than as sovereign entities.

India’s modus operandi for regional engagement follows a four-step process. First, it provides unwavering diplomatic cover to leaders who prioritize India’s interests over those of their own people. Second, it establishes bilateral institutional ties between the Bharatiya Janata Party and these leaders’ political parties. Third, it manipulates state-to-state interactions to politically benefit its allies, taking far more than it gives. Fourth, it fosters people-to-people connections exclusively with those who support the leaders identified in the first step. If these efforts fail, New Delhi labels its neighbours as bad actors.

To become the strategic partner the West desires, India needs regional buy-in from beyond the political sphere, especially with China firmly entrenched in South Asia and increasingly appealing as a dominant player to the general public in the region.

On August 26, during a call he initiated to Modi to discuss Bangladesh, President Biden signaled the United States’ desire for regional stability, likely reminding him of the importance of Indian leadership in achieving that stability. Reviving multilateralism via the moribund South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation may offer a path to reshape the regional landscape for the better.

Yale lecturer Sushant Singh wrote recently in Foreign Policy, “India’s tarnished image in Bangladesh is not the Modi government’s first major failure in South Asia, and it won’t be the last.” Only Narendra Modi can change course and belie that prediction.

Now, the ball is squarely in India’s court.

Policy Contributing Writer Aftab Ahmed graduated with a Master of Public Policy degree from the Max Bell School at McGill University. He is a columnist for the Bangladeshi newspapers The Daily Star and Dhaka Tribune, and his work has appeared in Canadian outlets like The Globe and Mail, The Line, The Hill Times, and Policy Options. He is currently a Policy Development Officer with the City of Toronto.

The views expressed in this article are his personal opinions and do not reflect the views or opinions of any organization, institution, or entity associated with the author.