Building the Bridge to a Post COVID-19 Economy

How do governments manage fiscal planning amid the unpredictable health and economic effects of a deadly pandemic? Former Parliamentary Budget Officer and President of the Institute for Fiscal Studies and Democracy Kevin Page assesses the Trudeau government’s effort to thread the needle.

Kevin Page

July 8, 2020

Federal Finance Minister Bill Morneau has tabled his 2020 Economic and Fiscal Snapshot. It is an important document. After four months of continuous updates from public health officials on the transmission of COVID-19 and spending announcements by federal political leaders, we now have a better understanding of the size of the economic problem generated by social distancing and other containment measures. It is a big, ugly hole filled with economic hardship and uncertainty; historic declines in output and employment.

The 2020 Snapshot is also important for what is not in the document. There is no forward-fiscal strategy and plan to address economic recovery. Simply said, the government is not ready for that kind of planning. Pressure will build on the government to release a strategy and plan when Parliament resumes in the early fall.

Is there a significant economic cost to policy uncertainty in the COVID-19 environment? Yes.

How will fiscal supports be unwound? Will there be replacement supports if unemployment rates stay in double-digit territory? What will be the policy response if there is a second wave of infections later in 2020? What will be the fiscal stance of the federal government in an economy where households are overloaded with debt, where many businesses see too many clouds to invest, and where global trade is shrinking?

This is information that people, businesses and bond raters want to know. A plan that addresses uncertainty.

I like the metaphor used in the 2020 Snapshot of building a bridge to the post COVID-19 economy. In the epic WWII war film “A Bridge Too Far” Field Marshall Montgomery was criticized for carrying out an operation that pushed too far. As the government knows, the fiscal snapshot is only the first half of the bridge. The recovery plan is the second half. No one could criticize the government for building a bridge too far.

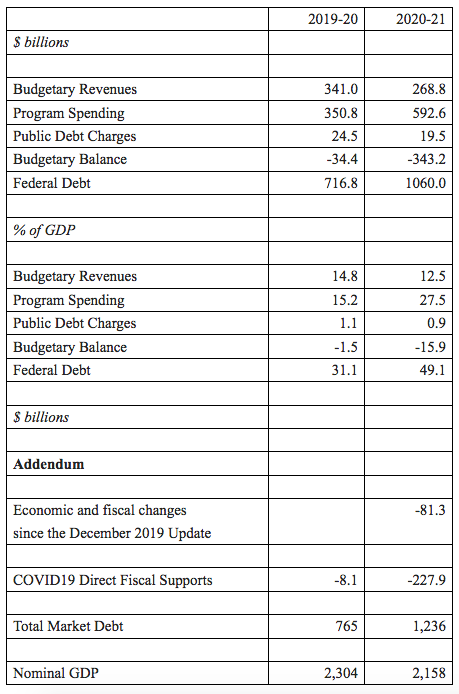

Table 1, Snapshot 2020, Statement of Transactions

What did the finance minister deliver with his Snapshot? We got economic and fiscal planning numbers for 2020-21; a statement of transactions (see Table 1 below); updated COVID-19 program numbers; and a debt management strategy. Like all updates and budgets, it is a snapshot – a point-in-time estimate of where things stand (in this case 2020-21).

I am glad the government released it. I am glad Parliament and the media pressured the government to release it. Let the debates on the role of fiscal policy be renewed.

The numbers exceeded expectations on deficits and debt. The Finance Minister tabled planning numbers for the budgetary deficit at $343 billion in 2020-21 (15.9 percent of GDP) and the federal debt at $1060 billion (49.1 percent). These numbers blew by earlier PBO estimates thanks to bigger estimated revenue impacts and re-estimated larger fiscal supports. Is it possible that actual numbers may come below these large deficit and debt estimates? I hope so.

Parliament and Canadians can use this document to make their own assessment of whether there was value for money in the significant fiscal supports. The government’s case on value for money is based on a public health strategy – lock down the economy to slow the spread of the virus and provide generous supports. There are numbers in the Snapshot (re. labour income and GDP) to make the case that they got the scale right.

At $227 billion in direct fiscal supports plus tax deferrals and liquidity measures (remember we are a $2.2 trillion economy after we lose close to 7 percent of GDP), did we get the scale right? Relative to other countries, Canada’s fiscal support package is on the large end.

Future generations will pay for this part of the bridge to the post-COVID-19 economy. They will pay for it in terms of some combination of higher interest on the public debt (do not expect interest rates to stay near zero forever); less fiscal room to address the next pandemic crisis or climate change, higher taxes or less generous government programs.

Just how expensive could the entire fiscal bridge be to the post-COVID-19 environment? If it costs more than $300 billion to keep people and businesses in lockdown, how much could it cost to build a sustainable, resilient and more equitable economy? It will not be cheap. The first half of the bill was about saving lives and livelihoods. The second half of the bill will be about building the future.

My take is that governments had little choice but to use deficit finance supports for the lockdown. Is it possible that the relatively larger fiscal supports (first half of the bill) will save social and economic costs (e.g., personal and business bankruptcy) during the recovery? Yes. In the future, economists will compare outcomes of different countries with the nature and scale of containment policy responses.

Still, we are reversing decades of hard-won progress in reducing government debt loads and interest charges. We need to see and debate the recovery plan before our elected representatives give the go-ahead. With the 2020 Economic and Fiscal Snapshot we got the plan and the bill after the taxpayer money had been committed.

Contributing Writer Kevin Page is founding President and CEO at the Institute for Fiscal Studies and Democracy at University of Ottawa, and was Canada’s first Parliamentary Budget Officer.